In the opening pages of his book Beloved Land, Gordon Peake described his first days in Timor-Leste. It was 2007, and while the Australian National University researcher sat in the patio of Hotel Timor, in the capital Dili, he noted that the voguish café was the preserve of malaes – foreigners, most of whom had come as advisors to help develop the newly independent nation. When he left the country four years later, many of the foreigners had gone and Hotel Timor had become a favoured haunt of the East Timorese elite.

Peake’s familiarity with East Timorese politics led him to a conclusion that, he said, outsiders often fail to perceive: it is a country of “family relationships, friendships, romances and antagonisms that collectively render ideas and concepts such as ‘accountability’ and ‘separation of powers’ almost completely impractical… Kinship and opaque connections are the ties that bind – not five-year plans and detailed strategic documentation.”

The East Timorese political elite is made up of a small cache of associated figures. Most fought during the 24-year independence struggle against Indonesian occupation and subsequently took up positions of power once independence was secured in 2002. But these intra-elite connections are often far from amiable.

Tensions date back to the independence struggle but came to the fore in 2006 when what started as disputes within the military soon became a battleground between the political factions, sparking widespread riots, mass displacement and concerns over the country’s future.

Xanana Gusmão, an independence hero and president at the time, had long harboured an intense rivalry with Mari Alkatiri, then prime minister and secretary general of the ruling political party, Fretilin. Alkatiri took much of the blame for the 2006 crisis – including allegations that he hired hit squads to assassinate political rivals, though these were most likely circulated by Gusmão – and eventually resigned, but not before insinuating that the events had been engineered with the intent to spark a coup against him.

The following year, Gusmão stepped down as president to establish his own political party, the National Congress for Timorese Reconstruction (CNRT). At that year’s parliamentary elections, which were marred by violence, the CNRT secured a majority of seats through a coalition with smaller parties and Gusmão became prime minister. Fretilin contested the constitutionality of the coalition and Alkatiri called for a ‘campaign of disobedience’ amongst supporters.

However, by the 2012 elections, which the CNRT also won, tensions between the two largest political parties had reposed and, three years later, rapprochement seemed a very real possibility when they formed a ‘national unity’ government.

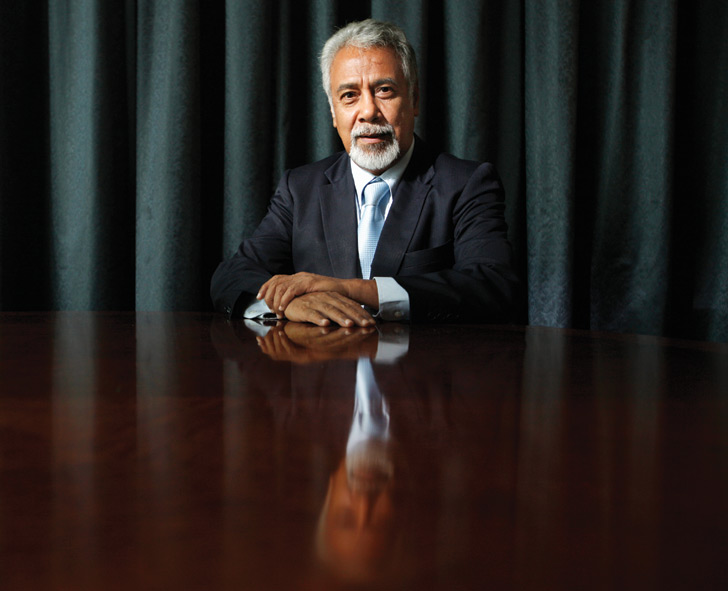

In February 2015, Gusmão announced he would resign as prime minister, and he nominated Rui Maria de Araújo, a former health minister under Fretilin, to take his place. This move promised to bring together politicians from the CNRT and Fretilin in a power-sharing agreement and end more than a decade of political instability.

At the time, Damien Kingsbury, a professor of international politics at Deakin University in Australia, told Southeast Asia Globe that Araújo’s accession was a “good outcome… he is competent, well liked and respected, and able to reach across the political divide”.

He added, however, with some prophecy, that the national unity government would leave Timor-Leste without a viable opposition and that by 2017’s parliamentary elections there would either be a return to political infighting or a slide into a “Malaysia-type domination of politics by coalition”. When interviewed again last month, Kingsbury said such cracks are now beginning to appear.

On February 26, Taur Matan Ruak, a former military commander who became president in 2012, stood before the country’s parliamentarians and announced: “The state of Timor-Leste is far too centralised. It centralises skill, power and privileges. It excessively wastes resources, allowing thousands of Timorese to become second-class citizens.”

The president alleged that the motivation behind forming the national unity government was not the public interest but the self-interest of officials, who could divide the country’s spoils between themselves. “They do not use unanimity to solve [Timor-Leste’s] issues; they use it for power and privilege. Brother Xanana takes care of Timor while Brother [Alkatiri] takes care of Oecussi,” Ruak said.

Oecussi is a small, impoverished district of Timor-Leste cut off from the rest of the country and surrounded on all sides by Indonesia’s West Timor province. A costly Special Social Market Economy Zone (ZEESM) is currently in development in Oecussi and, in 2013, Alkatiri was chosen by Gusmão to preside over this economic zone. According to the political grapevine, with tensions between the CNRT and Fretilin cooling, he was bought off by Gusmão and has used the ZEESM to enrich himself and his clique.

Such corruption allegations are a mainstay of East Timorese politics, with Transparency International ranking it 123rd out of 168 countries in its latest corruption index. Yet underhand dealings are utilised opportunistically and pragmatically. After becoming prime minister in 2007, one of Gusmão’s first tasks was to prevent another 2006 crisis.

“[The new government] gave rewards to the surrendering [military units] whose desertions from the army had set the crisis in motion, offered cash grants to persuade displaced [citizens] to return, funded lavish pensions for disgruntled veterans,” reads a 2013 report by the International Crisis Group.

As time went on, Gusmão became known for his propensity to ‘buy peace’, and the political stability achieved since the 2007 elections has been largely attained through the division of state contracts to veterans groups and between rival elites, according to a 2015 report by Development Progress.

“The allocation of contracts to influential elites is widely considered a necessary evil,” reads the report. “As one former Fretilin MP argued: it is ‘better to have people benefit from contracts, even [if they are] not awarded transparently, than fomenting coups’.”

There was hope that such logic would be abolished when Gusmão handed power to Araújo. However, Kingsbury said that, just a year later, optimism in Araújo is fading. He is widely seen as a “puppet for Gusmão” and government policy “doesn’t proceed unless Gusmão says so”. What’s more, Araújo’s policies are strikingly similar to his predecessor’s, including the distribution of state contracts to prevent hostilities.

When President Ruak addressed parliament in February and accused Gusmão and Alkatiri of corruption, it was nothing that journalists and political commentators hadn’t been talking about for years. However, Michael Leach, an associate professor at Swinburne University, Australia, told Southeast Asia Globe that a president partaking in such opprobrium was both “new” and “significant”.

“Despite the political stability and end to intra-elite tensions the national unity government has brought,” Leach added, “the downside is the lack of opposition. Whenever there is a vacuum, new players will enter.”

Ruak himself offered a similar sentiment: “Since there is no opposition party, the president takes on the role.” And one of his first acts as the self-ordained opposition came late last year when he attempted to veto the state budget for 2016. Under Gusmão’s administration, from 2007 to early 2015, state budgets grew substantially. And Araújo’s proposal for the 2016 state budget, at $1.5 billion, was almost equal to the previous year’s.

When they were in opposition, members of Fretilin, including Alkatiri, often criticised Gusmão’s expenditure, suggesting that too much went on costly megaprojects and vanity developments, which diverted vital funds away from healthcare, education and basic services needed by the maubere (masses). Another criticism was that the government’s ample spending was depleting the country’s finite financial resources. The vast majority of state expenditure comes from oil and gas revenues that are accumulated in a state-owned investment fund. However, as Southeast Asia Globe reported last year, these funds could be exhausted within a decade.

Despite Ruak’s efforts to veto the state budget, the country’s 65 parliamentarians voted it in unanimously.

A few months later, Ruak clashed with the national unity government again, when he refused to reappoint the commander of the Timor-Leste military. The move sparked calls by MPs for his impeachment, though commentators agree this is unlikely to happen.

Ruak’s opposition might stem from a genuine desire to hold the government accountable. As he told parliamentarians in February: “When the 2016 state budget was vetoed, members of parliament thought that I was defying their unanimity. However, I genuinely felt that I was… helping our people. I’m ashamed whenever I visit the sucos [villages].”

However, his stance as the government’s counterbalance could be pure politicking. According to Leach, Ruak is likely to join a newly formed political party, the People’s Liberation Party (PLP), and could run for prime minister at next year’s parliamentary elections. Ruak has made no public statement about his membership of the PLP – its current president is the former corruption commissioner, Adérito Soares – although it is widely believed to be the case by commentators and politicians. In November, a number of parliamentarians called for Ruak’s resignation, claiming it was unconstitutional for the president to be campaigning from office.

If Ruak does step down as president and run for prime minister on the PLP ticket, next year’s parliamentary elections could see two rival camps cross swords. Leach believes that the CNRT and Fretilin will compete separately but “a post-election alliance is clearly a strong possibility in light of the present national unity government”.

The domination of Fretilin and the CNRT at the polls will be hard to overturn. At the three parliamentary elections held since independence, the two parties combined have never achieved less than half of the national vote.

Nevertheless, Ruak is well liked in Timor-Leste. He was an independence fighter and military commander, and his populist position on spending more on ordinary East Timorese should win over swathes of the electorate.

“Most East Timorese support the reduction in tensions within the political elite that the national unity government has brought,” said Leach. “However, there are clear strains of dissatisfaction with the government’s development policies.”

To achieve electoral success the PLP might have to form alliances with other smaller parties, including the Democratic Party, which secured 11% of votes at the last election. However, its popular figurehead ‘Lasama’ de Araújo passed away last year, leaving the party without its linchpin. Leach is confident, nevertheless, that by next year’s election “Timor-Leste will see a new and substantial opposition force”.

Kingsbury agrees. Although he feels that, while opposition to the government will be beneficial, “there is too little [opposition] beyond the elites”. The fact remains that Ruak is just as much a member of the elite as Gusmão and Alkatiri.

Araújo’s accession to prime minister promised to usher in a generational and political shift – away from the politicians who fought for and won independence, and campaigned on the merits of this, toward a younger generation of leaders not beholden to the intra-elite tensions and connections formed decades ago. And away from consanguinity politics toward something more technocratic and formal. So far, this has failed to happen.

“This transition is still in its early phases, and it is a necessary one,” said Leach. “The 1970s and ’80s leaders of the resistance struggle, who retain considerable historic legitimacy, cannot be expected to govern Timor-Leste forever.”

All at sea

Timor-Leste’s critical maritime dispute with Australia explained

On 22 March, thousands of East Timorese gathered outside the Australian Embassy in Dili to accuse the Australian government of ‘illegally occupying’ disputed territory in waters off Southeast Asia’s youngest nation. Tensions date back to 1972 when Australia negotiated maritime borders in the oil-rich Timor Sea with Indonesia, then the coloniser of Timor-Leste. Once independence was achieved, many in Timor-Leste accused Australia of taking advantage of the oppressed nation to secure lucrative and ‘illegal’ ownership of its maritime areas. An agreement in 2006 essentially split the Timor Sea in half between Timor-Leste and Australia, but now protestors are demanding realignment.

The dispute is of huge importance as the oil- and gas-rich seas around Timor-Leste are vital for the country. According to the NGO La’o Hamutuk, 80% of the country’s GDP and 95% of its state budget comes from petroleum revenue saved in a national wealth fund. However, this pot might be exhausted within ten years and, without additional sources of oil and gas, which might lie in the contested maritime areas, the economic future of Timor-Leste looks uncertain.