Wanpen Pajai is the Globe’s reporter in Bangkok. She posts daily about Thai current affairs and the ongoing protests on her Twitter account.

Under the beaming sun on a Sunday afternoon in mid-August, sweat pooling behind my face mask, I sat with throngs of protestors on Ratchadamnoen avenue – a large thoroughfare near Chao Phraya river in central Bangkok. The capital’s Democracy Monument loomed in front, the golden representation of the 1932 Thai constitution manuscript glistened.

Crowded between people of a similar age – late teens to mid-20s – the demonstration on August 16 felt like Siam Square – a popular spot for young people to congregate and socialise on weekends. But instead, we were all there by choice, exercising our democratic right to protest.

A girl next to me multitasked, reading her chemistry study notes on her phone whilst cheering on the protest. Another raised a sign: ‘Let it end with our generation’.

“Down with dictatorship, long live democracy” the protesters chanted as they held up three fingers, a The Hunger Games-inspired three-finger salute that has turned into a hallmark of the recent pro-democracy protests.

“I came for my own future,” said Tarm, a university student sitting next to me at the demonstration. A student in her 20s, Tarm’s image – in which she’s holds up the salute while holding a sign reading ‘Where is my freedom? Where are my rights?’ – has circulated among the international press in recent weeks.

The day after the demonstration, high school students in over a dozen schools across Thailand raised the three-finger salute sign as they sang to the national anthem in front of the Thai flag, a display of support for the pro-democracy protests. Demonstrations held by university students have been a frequent occurrence in modern Thai history, but this was the first time high school students had been involved.

These acts of defiance are part of a wider youth-led revolt against the country’s leaders and structures. Further protests are scheduled on 5 September – organised by the Bad Student organisation with 24 high schools – and on 19 September, organised by United Front of Thammasat and Demonstration. The latter is expected to be the country’s next large demonstration, with Thammasat University historically at the centre of student protests, and the date, 19 September, marking the 2006 military coup that ousted former prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra.

These most recent pro-democracy protests have shaken and stirred long-standing untouched areas in Thai society, moving rapidly and creating ripples felt by all. Young Thais are standing up for their future, one that they do not see under the current military-affiliated government, and demanding reform to make Thai politics more democratic.

After over fourteen years of political uncertainty – two military coups since 2006, and six years of Prayuth Chan-Ocha leading the government – young Thais feel that the country is regressing and power is held by a small group of people insulated from the needs of the people, a situation further aggravated by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Still, the response to the movement, commonly viewed through the lens of being youth-led, has been jumbled.

Some have said that there is a generational gap and young Thais do not understand politics fully yet. The prime minister has said that ‘bullying’ is in place to pressure students to participate. Others say that the youth are being deceived into joining the protests – dismissing the message and intent of demonstrations.

These contrasting stances make it difficult to predict how the movement will end – something’s got to give if the vastly different perspectives of the students and the establishment are to be brought together.

“I’m constantly on Twitter, reading up about the flaws of the government. I talk about it a lot, but I want to take action and show up – that I’m one of many,” said Ploy, a 21-year-old university student who attended the mid-August demonstration. “I also want to hear what people my age, or people with similar views, have to say.”

The organisers of the demonstration, the Free People organisation, estimated that 20,000 to 30,000 people joined – the largest demonstration in Thailand since the military coup in 2014.

Speakers on the stage covered a wide range of topics – from the monarchy, human rights and inequality, to conflict in Thailand’s Deep South. Protestors signed petitions, made a wave movement, and passed an LGBTQ flag across the crowd.

As has been a constant theme of these protests, this particular event strayed into the boldest of territories, ending with human rights lawyer Anon Nampa saying “we dream of a monarchy that coexists with democracy”, followed by cheers from the crowd. Speeches were interspersed with musical performances and skits. It felt like a festival, a rare occasion in the recent pandemic times.

However, in the week following the demonstration, Anon, along with nine other activists, were arrested and then released on bail. While charged with sedition, this was undoubtedly part of a government crackdown on pro-democracy activists that have broken a long-standing taboo by calling reform on the monarchy, daring to walk the perilously thin line of what is deemed acceptable under Thailand’s harsh lese-majeste laws.

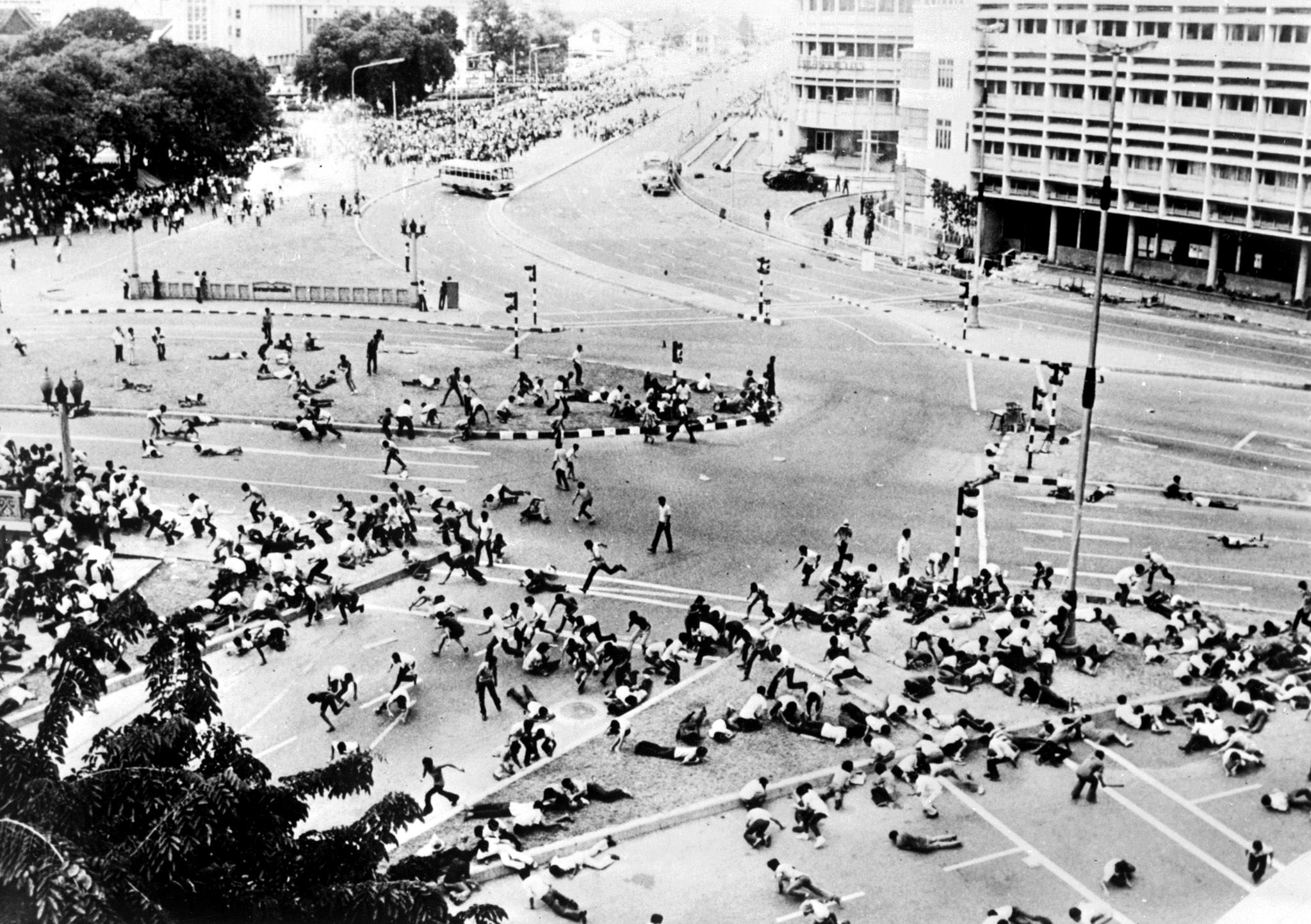

Anti-government demonstrations have occurred periodically in recent decades in response to military rule. For young Thais, their grandparent’s generation would’ve attended the 1973 uprising, their parent’s generation the Black May protests in 1992 – both events ended with bloodshed.

The trending hashtag of the demonstrations, ‘Let it end with our generation’, shows that young Thais are aware of the country’s repeating cycle of military coups and demonstrations. They are hoping to, once and for all, put a stop to this recurring pattern – for history to finally stop repeating itself.

The current pro-democracy movement kickstarted in February, when dissatisfaction from the dissolution of the Future Forward party led to flashmobs in universities.

Spearheaded by the charismatic Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit, Future Forward felt like a new and genuine option in the election. Instead of choosing the least-evil option, the party made younger generations feel that their aspirations could be realised through mainstream politics, creating a strong connection with the party.

Key to the movement’s growth has been Twitter, which has emerged as one of the main mediums for communication, allowing users to share quality information speedily, meet a community with similar views, and push agendas up through trending tweets.

Moreover, with the speed and convenience in accessing information provided by modern technology, it could be argued that young protestors today display a political maturity that is not so different from their older counterparts.

Both have influenced how young Thais engage in political discourse and the expectations they have from politics. Though they may be young, these protestors are not ‘kids’, and no longer feel obligated to defer to older generations as is traditional in Thailand.

Recent protests have been creative and connected to pop-culture references – from running like Hamtaro to Harry Potter-themed rallies – but beyond the themes, lay serious demands that come at quite a high cost for young Thai protestors.

This movement is truly organised by our generation, for our generation. We care about queer rights, women’s rights, true democracy, a just monarchy, activist safety, freedom of speech

“I went to protest because I’m fed up with the way our country is run. Ever since the 2014 coup, there hasn’t been an opportunity for citizens to freely demand change in the system,” said Tarm.

Protesters gathered in mid-August with three demands for the government: stop harassing citizens, draft a new constitution, and dissolve parliament. Recent events have only underscored dissatisfaction with the government. The military-appointed senate, the double standard in the rule of law with privileges for the elite, torture and enforced disappearances for people with dissenting opinions, and conservative values of what it means to be a ‘good citizen’.

“I feel particularly inspired to be part of this movement because I feel like it is truly organised by our generation, for our generation. We care about queer rights, women’s rights, true democracy, a just monarchy, activist safety, freedom of speech – the list goes on,” Tarm added. “For the first time ever, I am hearing my needs and my desires for a better country echoed on stage and all around me.”

Pressure on the government is growing as the economy slides into recession, hit hard by the Covid-19 pandemic. Last Monday, the government released statistics that Thailand’s economy has shrunk by 12.2% in the second quarter, the worst performance since the 1997-98 Asian financial crisis. Due to the impact of Covid-19, over 500,000 new university graduates are anticipated to face unemployment.

Across social media and in demonstrations, young Thais express their lack of confidence in the government to handle the economic situation, voicing their frustration about corruption and inequality, apparent in Prawit’s luxury watch collection, or even investment choices – most recently, purchasing submarines for 22.5 billion baht ($715,000) amidst the pandemic.

While demonstrations on the streets, in schools and on university campuses stand testament to the fact that the current government is failing to connect with Thailand’s younger generations, there were also older protesters scattered in the crowd on Sunday.

Yet, the protests are still regarded as a “youth” movement, with it still uncertain if it can cross generational divides – a chasm that Thai political discourse often fails to bridge.

In response to high school students showing the three-finger salute and tying white bows, reactions from teachers varied. Some punished students with verbal reprimands and physical punishment, further reflecting the authoritarian values present in Thailand’s education system that students are revolting against.

High school students quickly researched the background of teachers that condemned them for their political activities, finding that they too had attended anti-government protests organised by the People’s Democratic Reform Committee (PDRC) in 2013. The Ministry of Education minister, Nataphol Teepsuwan, was also a member of the PDRC himself. The irony was ridiculed on social media platforms.

Brought up in political conversations is the term ‘Salim’ – a colourful Thai dessert that during the Red and Yellow Shirts protests of recent years came to represent people that have swaying political opinions. It has now evolved to refer to people that have supported the PDRC, are against the pro-democracy movement, and support the current dictatorship.

At times, observing Thai politics feels like standing on a train platform. On the left, there’s a train travelling along, and on the right, there’s another train travelling at full-speed, except there’s not two-rails, but only a single-track. The challenge is how to not make the two trains crash – no one seems to have the answers.

In high schools, this dynamic is clear. Teachers are expected to teach students how to be citizens in society, but what we see now are students not agreeing with the values taught. The protests signal this contradiction – above all, the demonstrators want those in power to truly listen to their demands, engage in discussion, and recognise how they are part of the system they want to reform.

We’ve now reached an irreversible situation – discussions around the government and monarchy have started that can’t now be stopped. Youth protests show that government legitimacy is low and they’ve lost touch with the generation out campaigning. In this respect, the future for Prayuth Chan-Ocha looks dim.

“We’re out here because we don’t see another way in which our voices will be heard. And there’s no hope for young Thais, in a country that we will be in. We want to see change. We want for [the government] to listen,” said Tarm. “Maybe the most I can contribute is the space my body takes up, the words on my sign, and the information I share on social media. But I refuse to stay home when there is a chance I can be a part of change in this country.”

After sunset, under the mid-August twilight sky, Democracy Monument was filled with protestors swaying their mobile phone flashlights to the musical performance on the stage – the lyrics “we will not give up” echoing across the area.

“It makes me optimistic that this is the future of Thailand,” said Ploy. “The future is coming, you can’t stop this wave.”