“LGBT people are everywhere at every point in history,” said Aung Myo Min, executive director of Equality Myanmar and prominent LGBT and human rights activist.

A student leader during the 1988 democracy movement in Myanmar before being exiled to Thailand for 24 years, Aung Myo Min was one of the first openly gay men among the revolutionaries. “But, society in 1980s Burma made it incredibly difficult for people to open up about their sexuality and sexual orientation,” he told the Globe.

20-years ago last month, in July 2000, Aung Myo Min set up the Human Rights Education Institute of Burma (HREIB) – what would later become known as Equality Myanmar – to not only work to improve the rights of the LGBTQ+ community, but human rights across the country.

Two decades on, the work of Equality Myanmar and other civil society activists means that progress has been made to reform attitudes towards the community in the staunchly conservative country, with some LGBT candidates even contesting this November’s General Election.

But with homosexuality still criminalised, a military-drafted constitution in place ready to stifle reform on that front, not to mention gross human rights violations continuing to impact communities across the country, there remains a long way to go to cement civil liberties for Myanmar’s LGBT community.

If a year is a long time in politics, 32 years is an age – yet it seems in Myanmar attitudes towards the LGBT community, while loosened in some circles, remain little changed in others since Aung Myo Min’s participation in the 8888 democracy movement.

“The Buddhist religion is like most religions – it’s not really tolerant or friendly towards LGBT people,” said Aung Myo Min. “In Myanmar, there is a deep-rooted conservative culture within society and at the time, back in 1988, the space for LGBT people was very limited.”

As recently as May, a new school textbook provoked outrage as it featured a fictional same-sex couple, pushing boundaries and bucking tradition. The military-backed opposition Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), Buddhist monks and conservative parents called the book immoral and a threat to Burmese culture, demanding the Ministry of Education revise the book or throw it out completely.

“It would not be okay if same-sex case studies are in the textbook as it hasn’t been culturally accepted in our country,” Maung Thynn, a USDP MP, told German news agency DW in July.

Aung Myo Min joined the democracy movement on March 16, 1988 – four months before its peak in August that year – after witnessing student demonstrators from the University of Yangon beaten by police.

“I witnessed police brutally beating students, arresting them by force,” he said. “Many would later be tortured in prison and it made me outraged, I couldn’t tolerate the government and its actions anymore.”

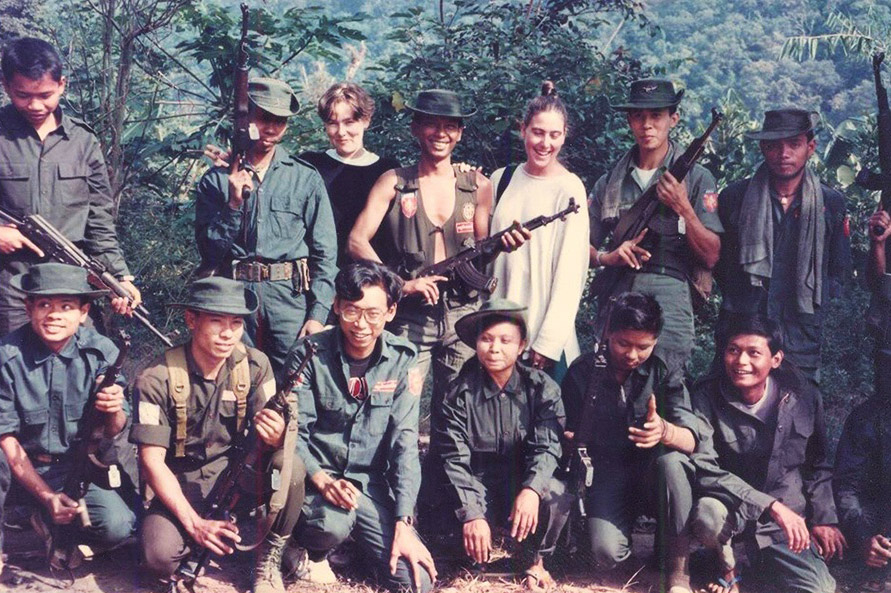

He would become a prominent student leader in the movement revolting against the country’s all-powerful and long-ruling military junta, before eventually being forced to the jungle along the Thailand-Myanmar border where he joined the armed student revolutionary group, the All Burma Students’ Democratic Front.

“I realised we were fighting for human rights – rights that were for everyone – and equality is the essence of human rights,” explained Aung Myo Min. “I asked myself, what is actually wrong with being LGBT? No one should be discriminated against because of their sexual orientation.”

But even within the solitude of the jungle and his fellow revolutionaries, prejudice against homosexuality remained. “When I first came out, not everyone from the group was supportive,” said Aung Myo Min. “I had to show my capacity and drive to work even harder to help the movement, to be accepted and recognised as an LGBT – it was not easy.”

The rights of the community have improved in some ways – now you see much more LGBT groups that encourage people to stand up and fight for their rights

He was forced out of the jungle by the encroaching military forces and exiled from the country soon after in 1989. During a period of exile from Myanmar that lasted 24 years, Aung Myo Min would settle in Bangkok where the drive for improving human rights in his home country would blossom from his new life in neighbouring Thailand.

“I had unfinished business,” Aung Myo Min said. “Myanmar was my home and I wanted to be close and work for my country and my people.”

He then established Equality Myanmar – then HREIB – in Chiang Mai in 2000 as a broad organisation to push for the improvement of human rights within the country, not just those of the LGBT community. The goal was to build a network of human rights trainers and advocates in Myanmar.

This goal has been achieved, but the push for LGBT equality has remained an ongoing and important struggle for the organisation. “From the very start we always had a focus on the LGBT community – the issue is my passion,” said Aung Myo Min. “LGBT people are human beings and their rights are human rights.”

In 2013, almost a quarter century after his exile, Aung Myo Min was allowed to return to home soil – and he and his organisation would begin fighting for equality much closer to home.

“The rights of the community have improved in some ways – now you see much more LGBT groups that encourage people to stand up and fight for their rights,” he explained. “It’s much less taboo, it’s more visible and the younger generation do express themselves and their sexual orientation more than we did.”

There have been some noticeable steps towards equality in Myanmar. LGBT people have been included as a ‘vulnerable group’ within the National Youth Policy in 2019, while the Child Rights Law of 2019 ensured a right to education, regardless of sexual orientation. Meanwhile, in December 2019, Myanmar’s contestant for the Miss Universe pageant, Swe Zin Htet, came out as gay just days before the contest. She was the first Miss Universe contestant from any country ever to do so.

However, with an election earmarked for November, Aung Myo Min admits that there is “a long way still to go” before there is equality between heterosexuals and homosexuals in the eyes of society and the law.

Despite Aung San Suu Kyi once calling for the decriminalisation of homosexuality in 2013, there has been little substantive progress on this front under her National League for Democracy party since they swept to power in 2015. To decriminalise homosexuality in Myanmar a 75% return would be needed in parliament – a seemingly impossible feat due to the fact 25% of the chamber’s seats are reserved for members of the staunchly conservative military under the 2008 constitution.

Homosexuality therefore remains illegal in the country, carrying a penalty of up to 10 years in prison. While not regularly enforced, the law still serves as a threat hanging over the LGBT community and law enforcement remains an obstacle.

“The attitude within the law enforcement hasn’t changed much – and homosexuality still remains illegal through Penal Code 377,” said Aung Myo Min. “It isn’t strictly enforced, but it is used as an intimidation and bribery tactic, specifically aimed at the transgender community.”

Instead of arresting, the police will often demand money instead. “The penal code is an ATM machine for the police,” he added.

You can’t go in all guns blazing, but instead think of the best entry point to raise the issue of LGBT rights. We must be smart to win over legislators

Being tactile in securing more rights for the community is part of how Aung Myo Min believes they will advance their cause.

“We must be politically shrewd with how we go about it – especially with legislators,” he said. “Sometimes, you can’t go in all guns blazing, but instead think of the best entry point to raise the issue of LGBT rights. We must be smart to win over legislators.”

Some of the parties contesting November’s election have openly gay candidates – a small number, but a number, nonetheless.

“That is a real breakthrough,” said Aung Myo Min. “[But] there is definitely still a long way to go.”

Aung Myo Min, rather than seeing his movement as seperate to human rights discourse in the long-volatile nation, regards the struggle for LGBT rights in Myanmar as one and the same as the broader struggle for civil liberties across the country.

“We’re not asking for special rights, just the equal, human rights, that we are entitled to,” said Aung Myo Min. “People sometimes ask, why are LGBT rights so important? Well, I say, they’re important, just as your own human rights are! There should be no difference.”