Earlier this year, a report published by UNICEF to mark the 25th anniversary of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action – the most comprehensive policy agenda for gender equality – described girls today as “unstoppable”.

Around the globe, women and girls are being praised for leading global movements on issues ranging from climate change to sexual and reproductive health rights, access to education and equal pay, with many lauding the girl child as an agent of change.

While this can certainly be the case, and often is, words such as unstoppable shift the burden of change onto girls and women without recognising or transforming the structural conditions that produce poverty, injustice and inequality.

Often the future is already scripted and not in the hands of the marginalised individual, but in the hands of the larger powers at play – community leaders, local authorities, policymakers, parents, teachers, governments, business owners and more.

In Laos, you can see these gendered power dynamics at play in the country’s education system.

While the Government of Laos prioritises human development as critical to staying on track to move from the status of a ‘least developed country’ to a ‘more developed country’ by 2024, troubling education patterns are seen in rural and remote ethnic minority communities, particularly among girls.

9% of females were married by the age of 15 in Laos, while 35.4% were married by 18. This is significantly higher than the global average

There is a significant gap between the deprivations experienced by majority Lao-Tai children – who speak the majority language and generally live in urban areas – and ethnic minority children who speak local languages and generally live in remote, rural and sparsely populated communities. For example, research from UNICEF in 2017 revealed that at primary level, 94% of children from the Lao-Tai group attend primary school, but only 83% of children from Mon-Khmer minority families do.

Within remote, rural communities, physical, structural and social barriers limit access to health, education and child protection services. This becomes even more pronounced when viewed through a gendered lens, with a 2016 study by Plan International Laos finding that gender beliefs and attitudes contributed to less value being placed upon girls’ education in ethnic minority communities, leading to girls not finishing school.

Often, the only avenue open to young women in Laos is starting a family.

According to Girls Not Brides – a global partnership of more than 1,400 civil society organisations committed to ending child marriage and enabling girls to fulfil their potential – globally, 20% of girls are married by the age of 18.

In contrast, 9% of females were married by the age of 15 in Laos, while 35.4% were married by 18. This is significantly higher than the global average, as well as the regional average. Thailand, representing Southeast Asia’s next highest rate of women married by 18, sat at 23%, while this drops to as low as 11% in Viet Nam.

Girls Not Brides describe marriage as being viewed as the only option for girls from isolated areas in Laos, something driven by traditional cultural beliefs. These gender dynamics are reflected in the education system.

According to Laos’ 2015 Population and Housing Census, the literacy rate of the population aged 15 and above in Laos as a whole was 85%. But obscured beneath this statistics is a large gender gap, with the male population found to be 90% literate, while only 80% of females were. Overall, the census also found that females were more than twice as likely to be unschooled than males, with 21% of adult females reported to have no educational attainment compared with 10% of adult males.

Beyond the gender discrepancies, further inequity becomes apparent when breaking the statistics down further, with the country’s lowest literacy levels found among the female population living in rural areas without roads.

Onglao (left) preparing lotus crackers (above) to sell in her village after receiving in business training from Aide et Action. Feung District, Vientiane province. Photo Aide et Action

Such disparity is directly linked to the entrenched norms where parents and other community stakeholders tend to believe that boys typically have more earning potential

For NGOs like Aide et Action, education is synonymous with empowerment and the development of autonomy over one’s own future. That’s why, in March this year, Aide et Action launched Education for Girls and Women Now – an international philanthropic campaign seeking investment in education to fight gender inequalities globally, from West Africa to South and Southeast Asia.

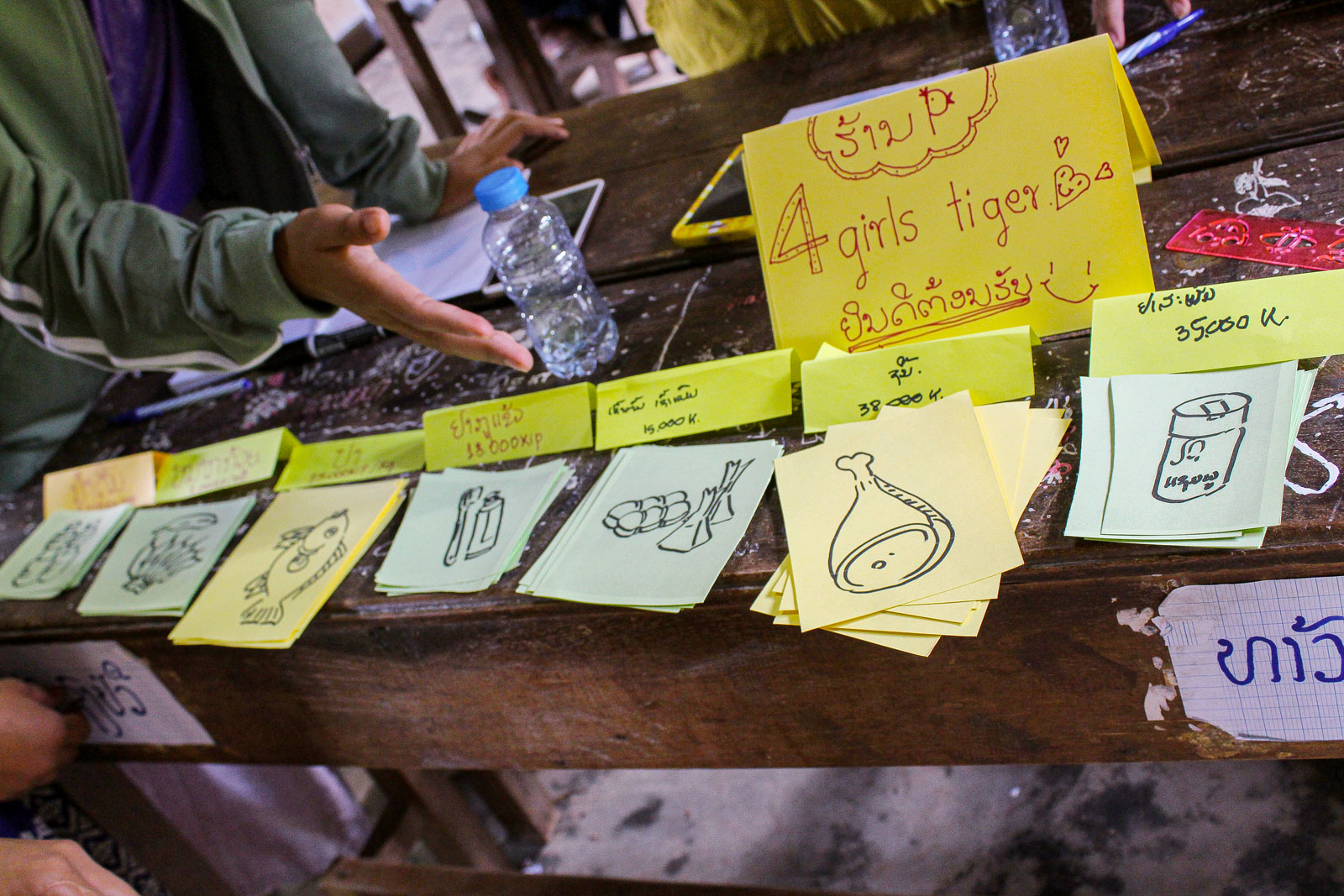

The project’s launch coincided with the conclusion of another one of the organisation’s projects – a Leadership and Entrepreneurship Camp for young ethnic minority women in Laos, supported by the British Embassy Programme Fund.

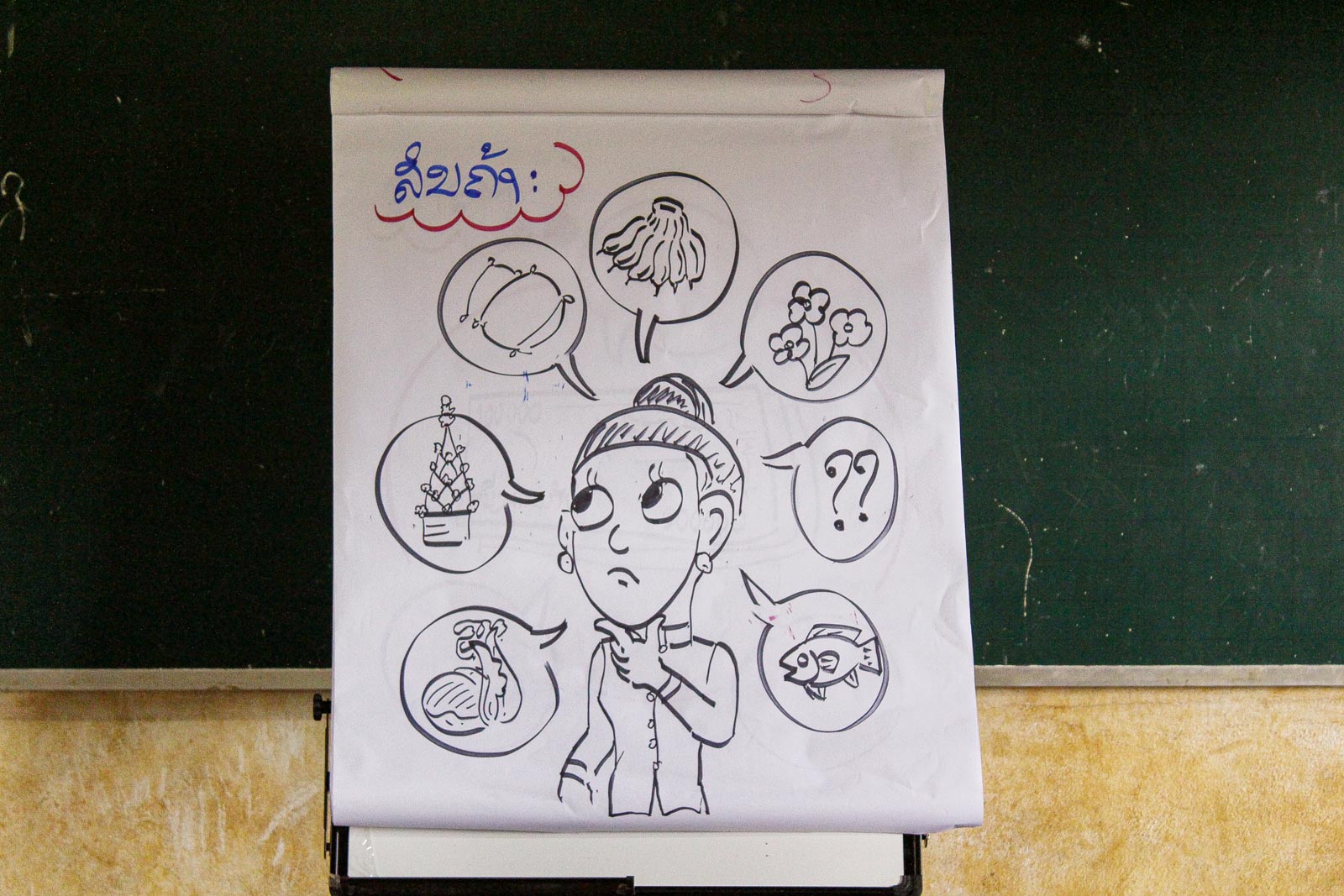

To reach those that hadn’t the opportunity to finish school and those at risk of dropping out, Aide et Action’s entrepreneurship camp focused on ethnic minority girls and young women aged 14-23.

From July 2019 to March this year, the pilot project reached 22 participants and worked in two villages in Vientiane province – Nongpor village and Phonsavath village, home to primarily Hmong and Khmu ethnicities which demonstrate strong traditional gender role divisions and educational disadvantages.

Such disparity is directly linked to the entrenched norms where parents and other community stakeholders tend to believe that boys typically have more earning potential and ability to support extended family members, compared to girls who are typically expected to marry and move to their in-laws’ families.

Such was the case for 16-year-old Yenkham who dropped out of school at Grade 9 so her parents could afford to send her siblings instead. When the chief of her village announced there would be a specific education project teaching business skills to ethnic minority girls in the village, Yenkham jumped at the chance to participate.

After completing the nine-month camp and receiving mentorship in designing and implementing a community-oriented business start-up with her team members, Yenkham decided to set up her own shop. After initial training on identifying and assessing community needs and economic potential, Yenkham noticed that her village did not have any retail stores and villagers had to walk long distances to buy goods.

A small grant scheme coupled with training sessions on business management, accounting, technical production and marketing carved a new path for Yenkham.

“After I participated in this project, my life changed a lot – I never thought that I could have a business and I had no knowledge of doing business, but I am doing it. By participating in the project, my living conditions have changed for the better,” she said.

Fellow participant, 23-year-old Onglao, also launched her own business with others from her village. Onglao is now selling lotus crackers to her community, something she never imagined she’d have the confidence or opportunity to do before the project.

“Most girls here dropout of school early to get married, to go to work at one of the factories in Vientiane, or to farm – I used to be one of those girls,” said Onglao.

While at the current rate, according to the World Economic Forum, it will take 108 years to close the inequalities between women and men and 202 years to reach parity in the world of work, projects like Aide et Action’s are increasing community awareness and participation in creating economic opportunities for women and girls, especially those previously denied an education.

Through offering participants mentorship in designing and implementing community-oriented business start-ups, the project sought to disrupt the norms that kept girls in low or unpaid agriculture, domestic and care work.

“Our experience is showing that young women, especially rural women from poor backgrounds, move on to become leaders for their community,” said Dr. Rukmini Rao.

Psychologist, activist and Indian magazine The Week’s “woman of the year” in 2014, Rao has been a member of Aide et Action’s Board of Directors since 2011.

Speaking about the organisation’s latest gender-focused campaign, she attests that if girls have increased access to education through the removal of the structural barriers that exclude them then they have the opportunity to become changemakers and more empowered.

Access to education – even for as little as nine months – has transformed some of the conditions that were producing poverty and inequality in this specific area of Laos.

Local authority figure Bounmy Kayong, Deputy Director of the Feuang District Education and Sport Bureau, noted that the communities involved had improved their capacity to earn an income and wished to see projects like this reach other villages.

“Expanding this activity to additional villages could benefit others and increase their income and employment,” he said.

What started as a small pilot project in two villages with 22 girls and young women has now grown to represent something much larger for some of the communities’ key figures – the realisation that more options can be created for young women other than child marriage, agriculture and unpaid domestic labour, and that such options may stand to benefit whole communities.

It takes a village, not a girl, to dismantle the gendered norms that limit empowerment. With community backing and increased access to educational resources, then we may be able to claim that these Lao girls will be unstoppable.

This article has been written by Aide et Action, as a part of a partnership with Southeast Asia Globe to highlight the need for equal access to education in the region. Find out more here