Visiting Dili in late August to mark the 20th anniversary of East Timor’s blood-soaked vote for independence from Indonesia, Australia’s Prime Minister Scott Morrison declared the opening of a “new chapter” in bilateral relations.

“In a region where some boundary disputes remain unresolved,” Morrison said, in a seeming reference to the disputed South China Sea farther north, “Australia and Timor-Leste have set an example by sitting down, as neighbours, partners, and friends, to finalise a new maritime boundary”.

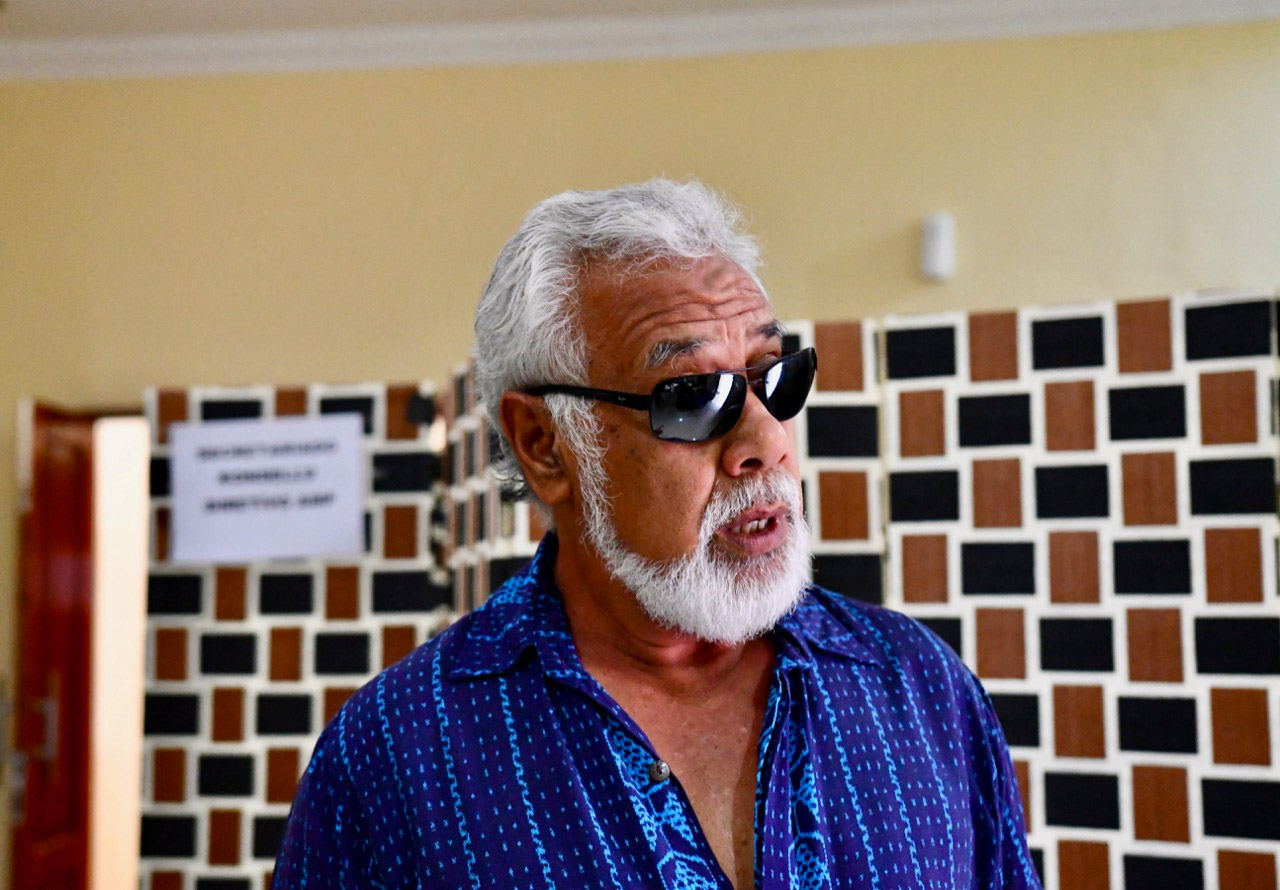

Though Morrison followed up by announcing plans to help upgrade East Timor’s internet connectivity and its navy, his Timorese counterpart Taur Matan Ruak was less gushing. “Today will mark a new beginning, a new phase for both countries,” he said. The implication, of course, was that the previous two decades of the relationship had been less than amicable.

While Australia stood by the hundreds of thousands of East Timorese who defiantly voted for independence in the face of scorched-earth Indonesian-backed intimidation, sending 5,000 soldiers to the country shortly after the vote, it later stood accused of strong-arming its tiny and impoverished neighbour out of billions of dollars of vital oil and gas revenues – in part by refusing to delineate a maritime boundary in the Timor Sea until 2018.

“Australia was not only taking billions of dollars from the second poorest nation in Asia, but it used espionage to do so,” said Tom Clarke, spokesman for the Timor Sea Justice Campaign.

That agreement arguably only came about after Australia was backed into a corner. Witness K, a former spy, and lawyer Bernard Collaery are facing charges of sharing state information about Australian surveillance of Timorese negotiators in the run-up to the signing of a 2006 maritime treaty – which East Timor promptly withdrew from once the allegations became public.

“Had it not been for Witness K and his lawyer exposing the Australian government’s wrong-doing, then we wouldn’t have a treaty today,” Clarke said.

Despite the sea boundary deal with East Timor, Australia has not dropped the charges against the whistleblowers. But with Dili hoping to join the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), a now ten-country grouping set up in 1967, Australia’s dealings with Southeast Asia’s second-smallest and newest state could have a bearing on attempts to move closer, diplomatically and economically, to the region.

“There’s no doubt that Australia’s reputation has taken a hit, and rightfully so. I mean, spying on your neighbours to cheat them out of their natural resources is a real dog act,” said Clarke, who is also director of campaigns at Australia’s Human Rights Law Centre. “Other countries in our region would be justified in being sceptical about Australia’s intentions”.

Hard choices

Despite being a U.S. ally, Australia is increasingly tied to China economically, leaving the so-called “Lucky Country” facing some hard choices as the two superpowers frame each other more and more as rivals amid rising tensions around tariffs, technology and China’s assertions of ownership of the South China Sea.

Former Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull acknowledged as much during his recent tenure, intimating in 2017 that Australia and Southeast Asia – which is similarly caught in the middle as the U.S. and China relationship deteriorates – could increase their collective bargaining power with the two giants by working more closely together.

Dismissing the notion that Australia will have to choose between China and the U.S. as “a false choice”, Turnbull gave a speech in Singapore in which he talked up the upcoming first-ever Australian-hosted meeting of Southeast Asian leaders as “an unprecedented opportunity to reinforce Australia’s strategic partnership with ASEAN”.

However, Australia’s relations with Southeast Asia have waxed and waned over the years. Singapore’s long-time Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew famously warned in 1980 that Australia could end up as the “white trash” of Asia if its economy continued to perform as poorly as it was at the time.

“I’d have thought ASEAN membership impossible for a range of historical and cultural reasons”

Frank Bongiorno, Australian National University

Lee’s choice of words was perhaps meant as a parody of the old “White Australia” policy, which was dispensed with in 1973 but which caused resentment across Asia by prioritising immigration from mostly European countries.

This year has seen another kind of trash-talking, with accusations from Malaysia and Indonesia, among others, that Australia and fellow developed economies are foisting their untreated rubbish on Southeast Asia in the aftermath of China’s recent ban on plastic imports.

Malaysia’s government accused wealthy countries of treating the region like “a trash can,” while there were protests in April outside the Australian consulate in Surabaya, the archipelago’s second city, over the recent surge in imported Australian rubbish at dumpsites in East Java.

Prigi Arisandi of Ecoton, a Surabaya-based conservation group, said that the rubbish trade had “gained a lot of attention from [the] government and community in Indonesia”.

The protests paid off, it seems, as both the Indonesian and Australian governments have said they will curb the waste export business.

“We are happy that the Australian prime ministry announced that Australia will stop export plastic scrap waste to other countries,” Arisandi said.

Elsewhere, Australia’s refusal to accept radioactive waste from a rare earths processing plant in Malaysia that handles materials mined in Western Australia, has not proved popular with locals near the facility. The Malaysian plant is the only major rare earths processing site outside China, which has threatened to restrict the international supply of the materials – vital to electronics and military hardware – should its relationship with the U.S. degenerate further.

Outpost

With nearly three decades of economic growth fuelled by booming natural resource exports to East Asia, Australia has put some of the earlier trash-talk behind it. The white part, it seems, is changing too.

Australia’s 2016 census showed over 896,000 people claiming heritage from ASEAN member-states, while visitor numbers showed Australia receiving more than 1 million visitors from the region. Australians themselves made almost 3 million trips to those countries that year.

Despite these growing connections, to some Asian leaders Australia remains “an outpost of Europe,” as Malaysian Prime Minister Mahahir Mohamad put it in an interview with Australia’s Fairfax Media in March 2018.

The ageing Malaysian leader’s remarks came shortly after Australia hosted its ASEAN meeting – a gathering that prompted visiting Indonesian President Joko Widodo, among others, to muse that Australia could join the group.

However Frank Bongiorno, head of the School of History at Australian National University, said that Australia’s close national security ties to the U.S. could prove a sticking point.

“Australia remains committed to the U.S. alliance and intelligence elements are very embedded,” he said. “I’d have thought ASEAN membership impossible for a range of historical and cultural reasons.”

ASEAN members such as Laos and Cambodia are increasingly seen as near-vassals of Beijing, a status that could be hard to square with Australia’s own close security links to Anglophone countries via the so-called “5 Eyes” intelligence-sharing nexus.

Mahathir sounded less enthusiastic than his Indonesian counterpart about Australia formalising its status as a Southeast Asian country. Referencing some of the differences between Southeast Asia and Australia, Mahathir told Fairfax that Australia “sticks out like a sore thumb”.

“The question is whether and when economic or security common interests will outweigh all these thorny issues”

Ariel Heryanto, Monash University

Indeed, relations between Australia and other Southeast Asian countries have typically been marred by flare-ups over unrelated issues. In Indonesia, these have included policies on stopping refugees and asylum seekers from entering Australian waters, beef exports, the often-comical antics of Australian tourists on the Indonesian island of Bali – and over the executions in 2015 of Australians accused of drug trafficking in Indonesia, with Indonesia stirring anger in Australia by rebuffing Australia’s requests for clemency.

Such disputes, acknowledged Professor Ariel Heryanto, director of the Herb Feith Indonesian Engagement Centre at Australia’s Monash University, “can make things difficult” for relations between countries. But Heryanto believes that Australia and Indonesia as well as Southeast Asia can develop closer ties, though disputes will “come and go.”

“The question is whether and when economic or security common interests will outweigh all these thorny issues,” he said.

Trading places

Australia does more business tied with relatively-distant East Asia than nearby Southeast Asia. Japan became Australia’s biggest trade partner over a half a century ago, a position it ceded in 2007 to China, which now accounts for around a third of Australia’s trade.

Australia’s trade with ASEAN as a whole is now a shade above trade with Japan or the European Union, though ASEAN’s population is around six times that of Japan and Southeast Asia is a lot closer to Australia than Europe.

However, Australia’s exports to some countries in Southeast Asia are minuscule, making up 2% or less of the goods brought in by countries such as Cambodia, the Philippines and Singapore, according to a recent report by the Australia-ASEAN Chamber of Commerce.

“I’m not suggesting Australia has not been interested in Southeast Asia,” said Bongiorno, “but economically North or East Asia have been much more important and that means Southeast Asia has somewhat been in the shadows”.

The Australian government has long flagged its hopes to move Southeast Asia into the light. In 2012, then-Prime Minister Julia Gillard said “thriving in the Asian century therefore requires our nation to have a clear plan to seize the economic opportunities that will flow and manage the strategic challenges that will arise”.

Gillard was launching Australia in the Asian Century, a hefty government blueprint weighing up how Australia could manage relations with Asia, which by then accounted for two-thirds of Australia’s trade in goods, up from just a fifth in 1960.

“When I talk to Australian businesses in Australia, there is a real ignorance about what is happening beyond Australia’s borders”

Ashley Irving, Australian Chamber of Commerce in Cambodia

Australia appears committed to open trade in the region, signing up to a revised version of the Trans Pacific Partnership deal even after the US withdrew in 2017. Only last weekend Australia expressed hopes that another deal, the slowly-incubating 16-country Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) – which takes in China, India, Japan, New Zealand, South Korea, as well as Australia and the ten ASEAN countries – would be agreed soon, even as the U.S. and China engage in what looks like an increasingly irreconcilable “trade war.”

Finalising the RCEP, as Australia’s trade minister Simon Birmingham told Singaporean TV station CNA – formerly Channel NewsAsia – on September 8, would “send a very strong signal that our region remains deeply committed to open trade, to growing our economies on a proven pathway of trade liberalisation.”

Seizing the day

While Australia’s 2012 Asian century plan asserted that “the Asian century is an Australian opportunity,” it remains questionable, nearly a decade later, whether Australia is poised to seize that opportunity, at least in Southeast Asia – despite official support for regional trade deals.

Australia’s trade is heavily skewed to China, Japan and South Korea – and investment remains “oriented much more towards ‘traditional’ markets such as the US and the UK,” according to Mark Thirlwell, chief economist at the Australian Institute of Company Directors, a Sydney-based industry group.

Recent surveys by accountancy firm PwC and by Australian business lobbies showed the level of Australian investment in Southeast Asia to be relatively low, even at a time when Southeast Asia is attracting record flows – a total US$127 billion in 2017.

“When I talk to Australian businesses in Australia, there is a real ignorance about what is happening beyond Australia’s borders,” said Ashley Irving, president of the Australian Chamber of Commerce in Cambodia.

According to the 2018 Investment Report published by the ASEAN Secretariat in Jakarta, 2016 and 2017 saw Australia outside the top 10 investment source countries into the region, outdone by far-flung competitors such as Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands and the UK.

Irving’s education company has operated in Cambodia for a quarter century, expanding in tandem with an economy that has regularly topped 7% annual growth over that time but still struggles to dispense with the image of an impoverished, conflict-wracked nation.

“Benefits such as ease of doing business here, the strong economic conditions, proximity to customers regionally, wide use of English are not well understood,” he said, challenging Australian businesses to ”come and look and make up your own minds.” Irving was adamant that “it will be more than worth the effort.”

The numbers so far suggest Australia’s businesses could remain reluctant to jump into some of the neighbourhood’s frontier markets. By 2018, only 4.2% of the total stock of Australian foreign investment was into neighbors in ASEAN. “Differences in culture, regulation etc. are typically going to represent more of a hurdle for an investment relationship than a trading one,” said Mark Thirlwell.

Such cultural and regulatory differences spill over, too, into region’s politics, with Australia struggling to juggle its stated commitment to freedom of speech with its desire to forge closer ties in a region where arguably only East Timor, Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines could be deemed democracies.

Along the lines of the dreaded choice, should it ever materialise, between China and the U.S., Australia might have to opt for either principle or pragmatism in Southeast Asia.

Patricia Fox, a Catholic nun from Australia who was recently kicked out of the Philippines, a majority Catholic country, for criticising the increasingly anti-Western Duterte government, said that Australia should review some aspects of its ties to the country.

The Philippines, like Australia, is a U.S. ally – though one that has not only drawn closer to China since 2016 but allowed the extrajudicial murders of an estimated 27,000 people as part of a government-sanctioned war on drugs.

“Australia should be looking into its aid, particularly military aid to the Philippines,” Fox said.

The need to balance against China and to forge closer relations with Southeast Asia was on clear display when Morrison preceded his East Timor trip with a visit to Vietnam a week earlier.

“You can see with Morrison’s visit to Vietnam that they’re interested in strengthening bilateral relations in Southeast Asia,” said historian Bongiorno.

Morrison’s Vietnam visit emphasised shared interests in the South China Sea, where China and Vietnam are engaged in a stand-off, rather than the differences between a single party state that jails pro-democracy activists versus Australia as an established democracy.

That said, with Australian whistleblowers facing jail for exposing the government’s spying on East Timor, Canberra might have reason to dial back the moralism as it tries to build closer ties with Southeast Asia.

“The Morrison government’s insistence that these two people now be punished, potentially with prison terms, doesn’t really suggest the government has changed its stripes,” said Tom Clarke.

The jailings, if they come about, could damage Australia’s reputation for transparency and undermine any image boost derived from the recent coming to terms with East Timor.

Australia, Clarke said, is “desperately trying to make friends in the region” – though he was sceptical that the lucky country would live up to its nickname. “Understandably it’s struggling,” he said.