Going by the sometimes breathless reports about how well Vietnam has done out of the US-China tariff joust, a reader would be forgiven for thinking that an authoritarian single-party state where farmers make up 40% of the workforce has been transformed into a kind of scaled-up Singapore, which despite its small size usually sucks in around half the annual foreign investment bound for Southeast Asia.

The numbers in so far suggest that Vietnam’s trade war triumph is indeed nigh. Its economy grew by just over 7% in 2018 – though that has dipped a notch, according to government statistics, to around 6.7% so far this year.

But even that slight fall-off will nonetheless make for high growth – due in part to record levels of foreign investment, including some business seemingly diverted to Vietnam as American tariffs add to the cost of exporting to the US from China.

“Following the US-China trade tensions, there is evidence of companies making adjustments to avoid the high tariffs situation,” said Bansi Madhavani, economist at ANZ Research, part of Australia and New Zealand Banking Group. According to Madhavani’s counterparts at Maybank Kim Eng, part of Malaysia’s Maybank, Vietnam “is emerging as the biggest beneficiary” of those adjustments, “with FDI [foreign direct investment] registration up by +86% in the first quarter of 2019”.

Rebaca Tan, assistant vice president and analyst at Moody’s Investors Service, predicted that Vietnam would continue to outpace its neighbours.

“We expect Vietnam’s real GDP growth to moderate to 6.7% in 2019 and 6.5% in 2020 from 7.1% in 2018, but even at these projected rates the country will still remain the fastest-growing economy in Southeast Asia,” she said in an August 19 Moody’s report on Vietnam’s banking system.

“If one of these key investors do not do well then Vietnam’s economic performance could suffer”

Le Hong Hiep, ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute

Data from the US International Trade Commission show Vietnamese exports to the US surging by nearly 40% during the first four months of the year. Vietnamese electronics sales jumped from 2.8% of US imports in the previous quarter to over 8% early this year – a jump that suggested “manufacturing lines in Vietnam are increasingly meeting the US’ electronics demands,” according to a July 31 report by Fitch Solutions Macro Research.

Pull factors, such as lower wages compared to China and officials keen for Vietnam to burnish its reputation as a manufacturing hub, have drawn in foreign electronics giants whose presence helps drive growth. 70% of Vietnam’s exports are sales by foreign investors, according to the Ministry of Planning and Investment.

“Vietnam’s skilled labour force and positive government support are its strongest assets and what initially drew us to the country,” said Ken Hong, senior director of global corporate communications at LG Electronics, a South Korean manufacturer of phones, televisions and kitchen appliances.

Guoli Chen, associate professor of strategy at business school INSEAD, echoed Hong’s assessment.

“Vietnam has several good advantages, such as a stable government that tries to attract FDI and make it easy to do business in the country,” he said.

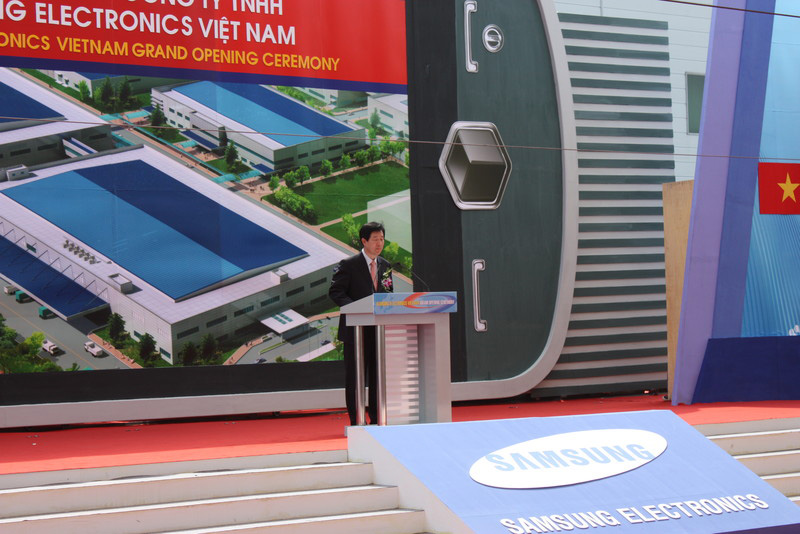

LG stated earlier this year that it would shift smartphone manufacturing from its homeland to Vietnam. But even that commitment is overshadowed by Korean rival Samsung, which has invested US$17.3 billion in Vietnam since 2007 and employs around 160,000 people in eight factories and two research and development centers.

Samsung’s 2018 exports from Vietnam were worth US$60 billion, up 12% from 2017 and making up a quarter of Vietnam’s total exports. The amount is more than double Cambodia’s 2018 gross domestic product (GDP) and tops Myanmar’s total economic output for 2015.

As source of around 20% of the country’s exports in recent years, Samsung’s pivotal role in Vietnam’s fast-growing economy means, however, that if sales should drop, Vietnam’s trade and investment dependent economy would surely be in for a jolt.

“If one of these key investors do not do well then Vietnam’s economic performance could suffer,” said Le Hong Hiep of the ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute, a Southeast Asia-focused think tank.

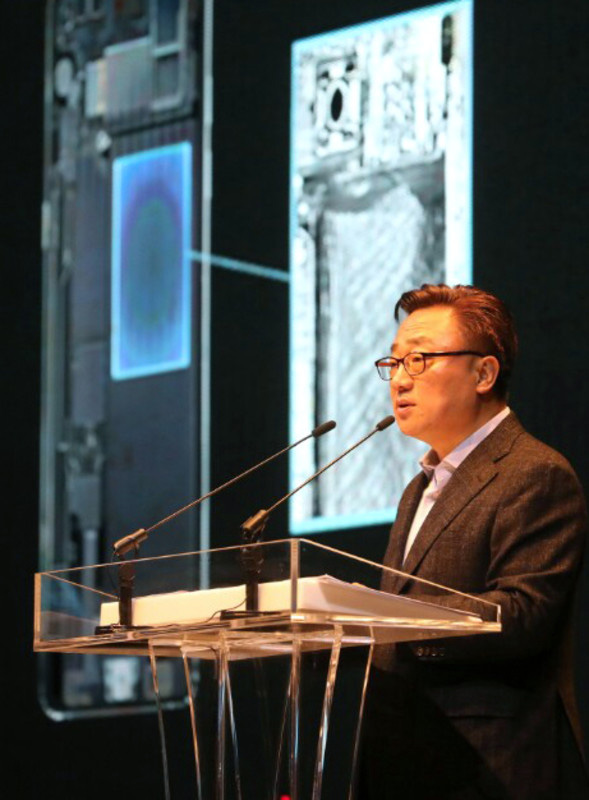

When Samsung pulled its Galaxy Note 7 smartphone from the market in October 2016 – after the devices started spontaneously catching fire, and Samsung shed US$26billion of its stock market value – Vietnamese officials and Samsung employees surely braced for the worst. Their fears were realised in part when early 2017 data showed a drop in quarterly GDP growth to 5.1%.

In the meantime though, Samsung, which did not respond to an interview request, put the Note 7 saga behind it, overtaking Apple as the world’s biggest smartphone maker by early 2018.

But even though Samsung came through the exploding phone saga relatively unscathed, it operates in a fiercely competitive market where fickle consumers crave innovation and reliability.

Tech companies such as Apple and Microsoft have come through falls and rises in the past, but former giants such as BlackBerry and Nokia can only reminisce, for now, about their long-gone heydays atop the mobile phone or smartphone sectors – lessons in how quickly tastes and trends can swing against complacent market leaders.

“If companies do not keep investing in R and D [research and development] and can innovate they will lose their place at the top,” said INSEAD’s Chen. “No matter how big a company is, it is difficult to stay successful even if the industry is stable.”

Three years on from Samsung’s dice with ruin, Vietnam depends heavily on the fortunes of major international businesses operating in a cutthroat market.

“We agree that Vietnam’s reliance on a small number of major foreign investors is a considerable vulnerability,” said Miha Hribernik, head of the Asia division at risk analysis company Verisk Maplecroft.

With one of the world’s highest trade-to-GDP ratios of around 200%, Vietnam is exposed should the trade war intensify beyond the current US-China stand-off or cause anything close to a global recession.

“The country’s increasing reliance on generating growth from exports mean it will not be totally immune to the global growth slowdown,” said ANZ’s Madhavani.

“Our strategy for Vietnam was put into motion long before the current trade issues began and our outlook for Vietnam remains the same”

Ken Hong, LG Electronics

Vietnam might be vulnerable in other ways – not least given that the recent jump in trade might be down in part to some nifty local repackaging of Chinese-origin goods by Chinese businesses attempting to side-step US tariffs.

Yuan Mei, assistant professor of economics at Singapore Management University, said that Vietnam’s trade war success would be diminished if the reports were true.

“Several anecdotes imply that some Chinese firms just ship their products to Vietnam for relabelling at ports before exporting to the US. If this relabelling exists extensively, then Vietnam will not benefit substantially despite the impressive increase in exports,” he said.

Vietnam has promised to crack down on the practice, no doubt jolted by President Trump’s June tirade describing the country as “almost the single worst abuser of everybody,” after its trade surplus with the US soared. On July 30, US Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer described the surplus as unsustainable, further stirring concerns that Vietnam could end up a victim of its own success and face American tariffs.

Earlier this year the US put Vietnam on a watchlist for countries meeting any of three criteria for currency manipulation. It seems unlikely, for now at least, that the US will take that any further, given tensions between Vietnam and China over the disputed South China Sea, where the US has accused China of “militarisation.”

Neither Vietnam’s foreign ministry nor the investment promotion ministry replied to requests for comment.

Another caveat to Vietnam’s apparent trade war triumph lies in how business had been heading its way long before any tariffs were raised.

Vietnam’s economy – spurred on by what the International Monetary Fund describes as “extensive market-oriented and outward-looking economic policies” – has tripled in size since 2000, with annual growth dropping below 6% only three times over the past decade.

“Our strategy for Vietnam was put into motion long before the current trade issues began and our outlook for Vietnam remains the same,” said LG’s Ken Hong.

Increasing operating costs in China have for some time prompted spendthrift manufacturers to look elsewhere.

“The shift in manufacturing from China to Vietnam has been happening for several years, with comparatively lower labour costs the main ‘pull factor,’” said Verisk Maplecroft’s Hribernik.

“Positive structural changes in the economy and ongoing reforms mean Vietnam is much better placed to weather external headwinds compared to other economies”

Bansi Madhavani, ANZ Research

Since Vietnam joined the World Trade Organisation in 2007, annual growth rates have often matched or exceeded those seen since the first shots of the trade war were fired in early 2018, when US tariffs on imports of aluminium, steel, washing machines and solar panels prompted Beijing to hit back with levies on 128 American exports to China. In 2017, the year before the trade war started, Vietnam pulled in almost double the US$7.4 billion worth of foreign investment it received in 2011.

While Bangladesh, Cambodia and Myanmar all have preferential trading arrangements with the European Union and the US – the terms of which helped persuade clothing and shoe manufacturers to shift production from China before the trade war – Vietnam has spent the past several years lining up trade and investment deals with the EU that go beyond the preferences given to poorer countries in the region.

Vietnam has also signed up to the 11-country trade pact now known as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), after the Trump administration withdrew the US from the original TPP. Vietnam is also party to the Association of Southeast Asian Nations’ free trade deal with China, which dates to 2010.

With a report last year by the Vietnam Chamber of Commerce and Industry estimating that only 14% of Vietnamese companies are suppliers for multinational corporations operating in the country, the hope appears to be that trade deals can spur local companies into upping their game.

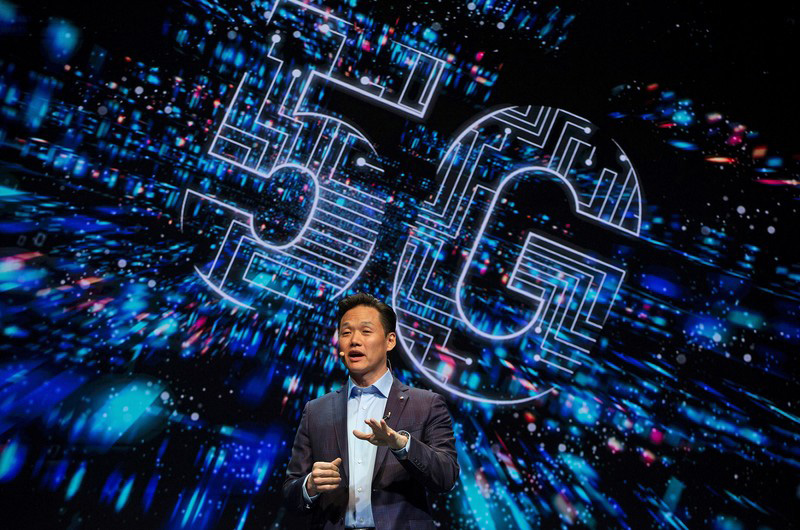

“The government is keen to grow domestic companies to make Vietnam less vulnerable,” said Le Hong Hiep. He pointed to locally made smartphones by Vingroup, a conglomerate, and state telecommunications provider Viettel’s attempts to spearhead the development of a 5G network as examples.

The government said in mid-August that it intends to sell stakes in around a hundred state enterprises – privatisations that are required of the communist-run state by some of the trade and investment agreements.

“I think the government sees the trade deals as a way to get domestic business used to competition,” Le said.

The World Bank’s latest annual Doing Business study – which, as the title suggests, ranks each country on ease of doing business, using criteria such as company registration, investor protection and access to electricity – saw Vietnam jump 14 places to 69 out of the 190 countries assessed, a steady increase from 87 a decade ago. The World Economic Forum’s 2018 Global Competitiveness Report had Vietnam holding at a mid-table 77, out of 141 countries.

Even though Vietnam ranks well below neighbours such as Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand, an improving business environment could help it repel any trade war shrapnel. “Positive structural changes in the economy and ongoing reforms mean Vietnam is much better placed to weather external headwinds compared to other economies,” said Madhavani.

Given Vietnam’s burgeoning role as a low-cost electronics hub, even another exploding phone saga might not dent its prospects anytime soon, not least as Samsung quickly put that 2016 debacle behind it.

“Even if one firm decides to relocate its factories, new firms will enter if the labour-cost advantage is attractive enough,” said Yuan Mei.