Though Lway Hlar Reang is not involved in any of Myanmar’s many ongoing internal conflicts, she works on the front line in the fight against the country’s rampant landmine problem. When asked how many people she has personally known to have died after encountering the landmines, she pauses for a moment.

“Ten … maybe fifteen. Ten to fifteen,” she tells Southeast Asia Globe. “This year.”

In October alone, Hlar Reang says, there have been five deaths in her community in Lashio, northern Shan State’s largest town, with over 30 injured.

She is the general secretary of the Ta’ang Students and Youth Union (TSYU), a grassroots organisation based in Lashio. Nestled in the northeast of the country, 200 kilometres from Mandalay, the township overlooks the valley of the Yaw River that has seen a spike in recent years in the long-running conflict between ethnic armed groups (EAGs) and the government.

She says the majority of people living in the area have been affected by landmines in some way, whether they’ve suffered a direct injury or have had a family member or friend injured or killed, adding that these numbers seem to be steadily increasing.

Bleak testimonies like Hlar Reang’s can often be the clearest way to get a gauge on the human impact of the use of landmines, as it remains incredibly difficult to accurately measure the number of casualties. But though her anecdotes are jarring, they represent just a fragment of the ongoing reality for communities all over the country.

For the second year in a row, the International Campaign to Ban Landmines has found that Myanmar is the only country in the world where the government is still laying new landmines. The 2019 edition of the organisation’s annual Landmine Monitor report, released on 21 November, confirms the new use of antipersonnel mines from mid-2018 through October of this year.

In total, it estimates that 430 people were killed by landmines in Myanmar in 2018 – more than double the previous year’s estimates. This places the country fourth highest in the world – after only Afghanistan, Syria and Yemen, all host to among the world’s most deadly ongoing conflicts – and among a select few in which casualties are increasing.

Contributing to this is their continued use among EAGs, with the Kachin Independence Army, Arakan Army, Democratic Karen Benevolent Army, Karen National Defense Organization, and the Karen National Liberation Army all implicated.

If you were to ask me today how many casualties there are [in Myanmar], after looking carefully for almost a 20-year period … I’d have to say we don’t have a clue

Dr Yeshua Moser-Puangsuwan, research coordinator and editor for Landmine Monitor

Ask researchers with knowledge of Myanmar, and they will likely tell you that there is a dearth of public information on most issues impacting the country. Narrow the scope to the highly contentious issues of war and violence, and finding out what you want to know becomes even more complicated.

Dr Yeshua Moser-Puangsuwan, a research coordinator and editor for Landmine Monitor, says the report’s numbers are likely far lower than the reality, and should be regarded as a minimum estimate of total casualties. The Burmese military has told Moser-Puangsuwan that their personnel suffer casualties from landmines more so than any other cause, but they refuse to provide him with the actual figure. EAGs are similarly reticent on the issue.

“If you were to ask me today how many casualties there are [in Myanmar], after looking carefully for almost a 20-year period and mining every available source of data, I’d have to say we don’t have a clue,” he said. “And there are no official statistics.”

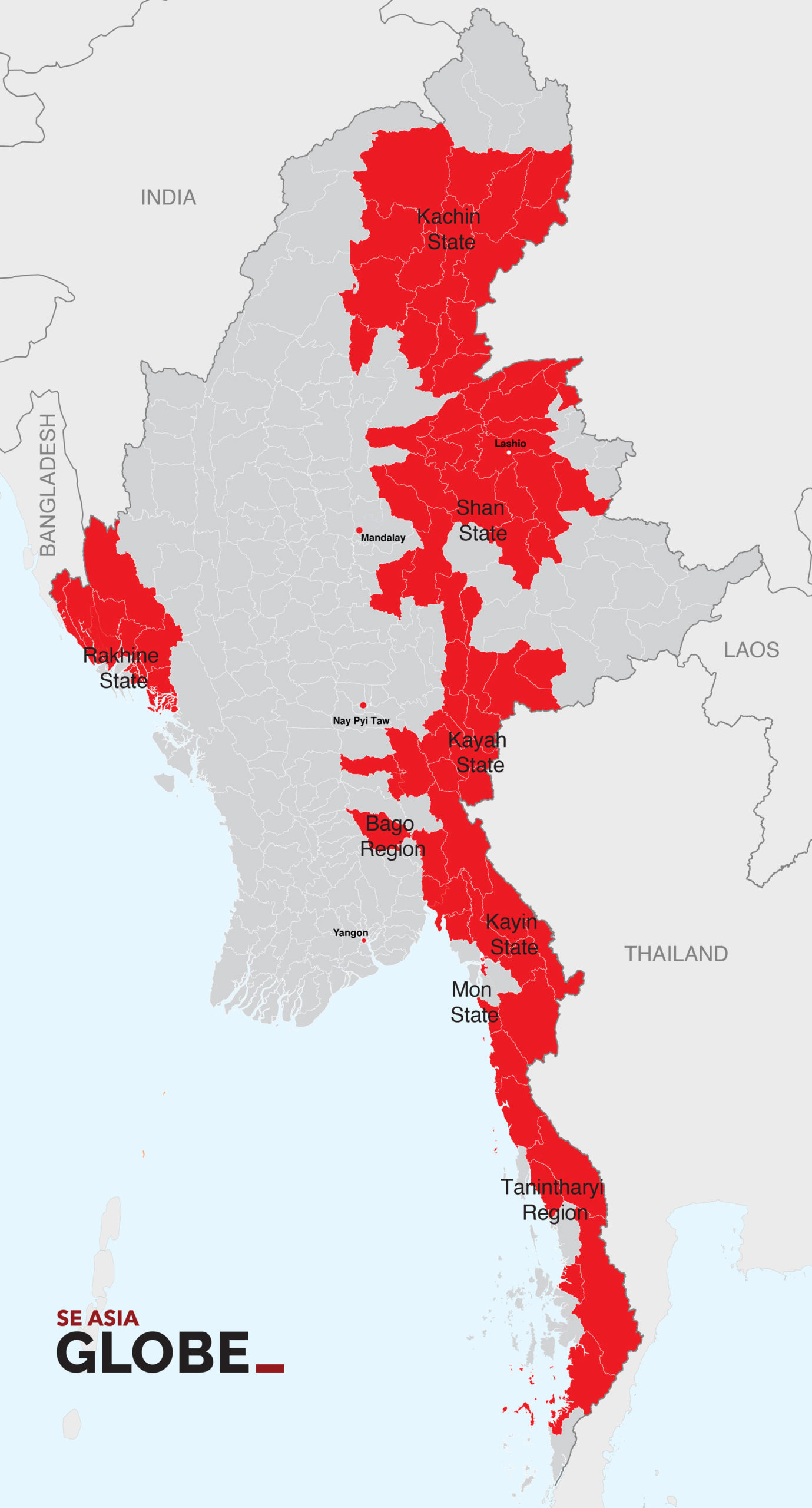

Landmine Monitor has confirmed the presence of landmines in townships stretching almost the entire length of the country, from north to south, as well as in the west in Rakhine state.

With no formal government-led initiative tracking landmines, typically the organisation receives their information from informal grassroots sources. This can include word of mouth, such as locals being informed by soldiers that a certain area is no longer safe, and those locals passing the news on. Inevitably, such an informal system for such a perilous problem contributes to the casualties.

Meanwhile, the continuing proliferation of mines continues to encroach on land previously considered safe, penning communities into smaller and smaller spaces. “More and more land is not available to the people of the country to carry on their normal daily activities,” said Moser-Puangsuwan.

Exacerbating the issue

Globally, anti-personnel mines are fast becoming a relic of the past, with their continued use increasingly controversial as the world redefines what is acceptable conduct in war. In a 2017 report, academics with Queen’s University Belfast wrote that their use, when indiscriminate and causing unnecessary suffering, should be classified as a war crime.

This newer mentality around landmines was beckoned by the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention – known as the Ottawa Treaty, which came into force in March 1999 – as the international community responded to what it saw as a widespread humanitarian issue.

As of 1 November this year, 164 countries are “bound by and are dutifully implementing the treaty’s provisions”, according to Landmine Monitor’s analysis, with most of the 33 non-signatory countries – which includes the US, China and Russia – nonetheless abiding by its key provisions.

Unsurprisingly, Myanmar is among the 33, but unlike the majority of its fellow non-signatories, it does not abide by its provisions.

Decades of conflict between government forces – known as the Tatmadaw – and numerous EAGs have resulted in the country being blanketed with thousands of mines in recent decades. The landmark 2016 election victory for then-democracy icon Aung San Suu Kyi and her National League for Democracy party in the country’s first openly contested polls since 1990 were widely regarded as offering hope for ending many of these ongoing conflicts.

But just a few years on, a resurgence of fighting and widespread violence has made an end to landmine usage look no closer.

Since Myanmar’s nominally-civilian government assumed power in 2016, the Tatmadaw has reportedly undertaken sporadic mine clearance operations, but they have not been systematically recorded. Meanwhile, authorities have not permitted any humanitarian organisations or bodies to engage in mine clearance operations, limiting the role of groups like HALO Trust and Norwegian People’s Aid to mine risk education and victim assistance projects.

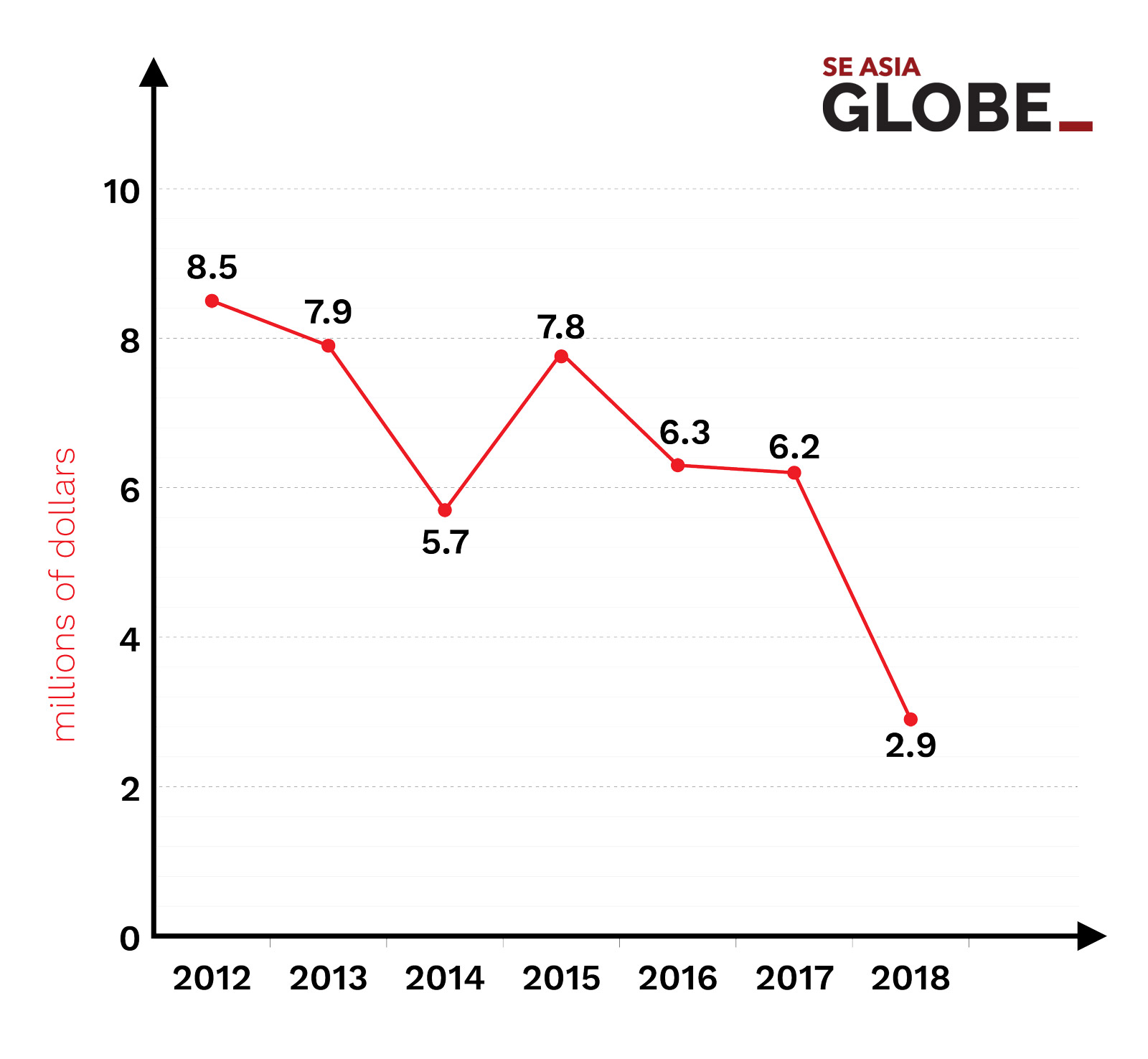

Recent data suggests that the military’s restrictions on mine clearance operations may be having a negative impact. According to research from the Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor, international aid slotted for the landmine issue in Myanmar has dramatically decreased in recent years.

While in 2012 Myanmar received $8.5 million in funding towards landmines, in 2017 – the year Burmese security forces began an assault on Rohingya Muslims in Rakhine State widely condemned as a genocide – the country received $6.2 million. By 2018, that number had more-than halved to $2.9 million. This sits in stark contrast to the global trend, in which international aid for landmine issues has increased by almost two-thirds since 2015.

But as some donors pledge multi-year financing for demining projects, year-by-year funding comparisons prove little on their own.

Moser-Puangsuwan adds that one year’s data is not sufficient to establish a downward trend in funding, nor establish the uptick in conflict as the cause of this downward trend. However, he said that the current environment in Myanmar could be off-putting for some organisations.

“[Countries] are seeking to fund mine clearance. If no mine clearance is going on, then they are probably taking their money elsewhere … You can’t draw a really firm conclusion from it. But what I can certainly say is, there are at least two donors who have decided that, ‘well, mine clearance isn’t happening, we’ll come back later when it is,’” he said, declining to specify which donors.

This apparent step-back from international organisations in their demining efforts in Myanmar has not gone unnoticed. After Landmine Monitor’s 2019 report was released, Mark Farmaner, Director of Burma Campaign UK, said the lack of attention given to the issue of landmines by international donors was “a disgrace”.

“It is beyond belief that rather than massively scaling up mine clearance and education programmes in Burma, donors are actually cutting them.”

Local impact vs international attention

On 24 November, a German man was killed and an Argentinian woman injured while hiking in Shan State’s Hsipaw township, with global news outlets picking up the story.

Unsurprisingly, local casualties, such as those described by Hlar Reang, rarely receive the same media attention. The same day as the foreigner’s deaths, a Rohingya man was killed by an anti-personnel landmine and two others injured on Myanmar’s border with Bangladesh.

“Even news media groups as well, they are not really concerned about the landmines,” said Hlar Reang. “But when one of the foreigners [gets hurt], it comes up a lot.”

Without the assistance of larger organisations for mine clearance and limited funding of their own, local organisations like Hlar Reang’s organisation the TSYU place a huge emphasis on mine risk education and victim assistance. Staff take groups on walks in order to teach them how to identify mines and report dangerous locations.

This is simple but necessary work in a region where landmines are a daily fear for people farming and foraging to provide for their families.

Globally, it’s a pivotal time for those campaigning to ban mines, with the Fourth Review Conference of the 1997 Mine Ban Treaty held in Oslo, Norway from 25 to 29 November. The review conferences are held every five years and are meant to “re-energise” the convention’s work, according to Hans Brattskar, the convention’s former president ambassador.

Myanmar’s Minister of Social Welfare, Relief and Resettlement Win Myat Aye attended this year’s event as an observer and delivered a statement, but he made no reference to the country’s use of landmines, according to conference attendees.

Brattskar, who recently concluded his term, says their approach is less about pressuring Myanmar and more about making the country aware of mine action possibilities.

“We try to tell them that full membership is really what we hope for, but we ask them to approach the convention so they can learn more about what the disarmament community is all about,” he told Southeast Asia Globe.

During the Oslo convention, a Bangladeshi representative took to the stage to condemn Myanmar’s continued use of anti-personnel landmines, saying those allegedly laid on their shared border – the route for fleeing Rohingya – have caused numerous casualties. Fittingly, Myanmar, whether by design or accident, was not present in the room when the statement was made.

As November’s conference wrapped up, state participants recommitted to striving for a mine-free 2025 and adopted 50 action points to ensure mine clearance and other treaty obligations are met by that deadline.

On Myanmar’s commitment to demining efforts, Moser-Puangsuwan remains cautious, but not without optimism.

“We’re not satisfied, but I can’t say there’s absolutely no change. And we continue to encourage them to halt the use of landmines immediately. What else can we do?”

But while spreading word of Myanmar’s ongoing conflicts and creating a peaceful nation remains crucial to the safety of its people, Hlar Reang says in the meantime she also hopes the devastating impact of Myanmar’s landmine problem will receive the attention it deserves.

“Maybe one day,” she says, the uncertainty evident in her voice.

Have you been impacted by landmines in Myanmar? If one of your family members or friends was killed, you have been injured by landmines or you are unable to go back to your home because you fear landmines, we want to talk to you. Email s.mccabe@globemediaasia.com to chat.