A stack of flashcards, each printed with a QR code, sits unassumingly on the edge of the programmer’s desk. The cards seem almost out of place in the high-tech office, where virtual models of explosive weapons are configured and modified on every computer screen.

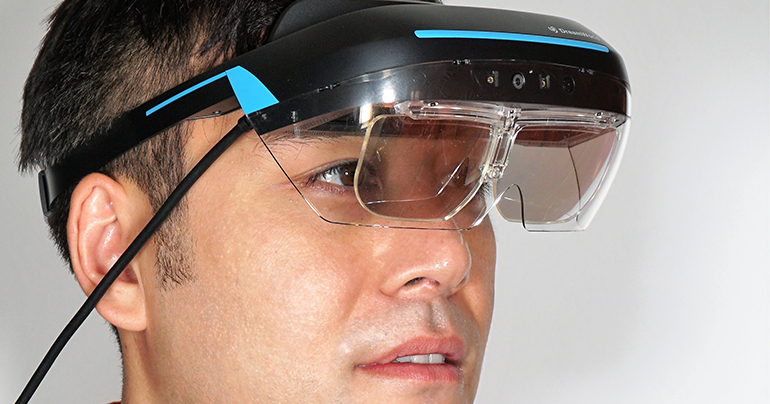

It is only when wearing the augmented reality (AR) headset that the flashcards come to life.

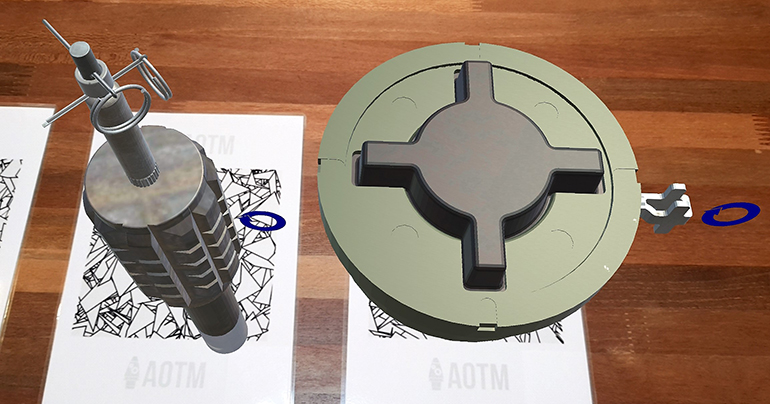

The headset focuses in on a QR code and a device appears in midair, hovering just a few centimetres above the card, a perfect representation of an explosive ordnance floating within arm’s reach. With a small tap to the right of the headset the explosive springs to life, its pieces coming apart and reassembling themselves. With another tap, the ordnance ignites.

“Using this tech, you can see how the mortar works, you can zoom in on the fuses – you can zoom in on anything you want to see,” explained Allen Tan, director of applied technology at Golden West Humanitarian Foundation, as he flipped through the hefty stack of QR cards in his team’s Cambodian laboratory.

Golden West, a nonprofit funded by the US State Department, has a singular purpose: to safeguard communities from life-threatening munitions that continue to pose a threat, especially in heavily mine-impacted countries like Cambodia and Vietnam.

Most recently, the organisation has been pioneering AR technologies that could prove game-changing for bomb defusal teams around the world.

While the AR headsets are thus far used only in tandem with the QR codes, Tan’s team expects that in the near future, the headsets will allow technicians to look at an explosive and – in real time – be told what type of bomb they’re seeing and exactly how to dismantle it.

“When these goggles get better, you’re actually going to be looking out at the world, wearing these goggles out into the field while you’re doing operations,” explained Tan, adding that an improved version of the AR headsets would be available later this year, at which time their use in the field would be highly likely.

“The way bomb disposal currently works is this: they call and you come. You take pictures and measure the ordnance, and then look it up on your tablet or phone to know what it is,” said Tan, adding that this method is often time-consuming and prone to human error. “But with goggles, you can identify the bomb almost instantaneously and then you can see how it works in real time, and figure out how to best destroy it.”

The first hurdle to improving bomb disposal techniques, Tan said, has been establishing a thorough online database of explosive munitions, which the Golden West team has been working on for years. Prior to these efforts, the most comprehensive list of munitions available to defusal teams was in the form of a poorly-drawn and difficult-to-peruse PDF.

“Imagine you’re a guy trying to fix a car – bomb defusal is similar. You need to understand how the machine works, and a set of pictures in a PDF is just not enough” said Tan. “But this technology is a game changer, because now you can see all the pieces and parts of these bombs in perfect detail – this kind of data does not exist in this form anywhere else.”

As its database has grown, the Golden West team has also developed a set of machine learning algorithms that, once perfected, can eventually be married with AR headset technology to allow the quick and accurate identification of in-field explosives.

“When I was in Iraq with the US Army, some guys would pick up bombs they thought were one type when they were actually filled with chemicals that would cause their skin to blister,” he said. “If the computer can tell you what type of bomb it is you’re dealing with – from the angle of the curve, or from a rusted piece the naked eye can’t see – then it can really help.”

While the full integration of AR may be yet to come, the database as it currently stands has already proven invaluable for defusal, as teams across Europe and Southeast Asia have been using it as a tool for teaching aspiring bomb technicians how explosives work. So too are the AR headsets in their current forms also proving useful, as students are using them to familiarise themselves with 4D versions of the bombs listed in the database.

Vietnamese defusal teams have also been known to use the headsets and their accompanying QR codes out in the field, using the tech in the process of double-checking they’ve accurately identified an unexploded ordnance. Flipping to the QR code for the bomb they’ve identified, technicians can use the headsets to refresh themselves on exactly how the bomb in question should be dismantled.

“We’re still a way from robots doing the demining for us, but our teams are already machine-assisted, and it’s really helped cut down on mistakes in disposal,” Tan said excitedly. “Machines can’t replace human judgment, but they can definitely help.”