This story was originally published on Malaysian environmental journalism site Macaranga and republished on the Globe as part of a content sharing partnership.

Tour guide Ahmad Shah Amit had been looking forward to the summer holiday season in Europe. In any other year, European tourists, up to 1,000 a day, would flock to the wildlife-rich Kinabatangan region in Sabah.

There, they would pay locals like Ahmad, popularly know as Tapoh, to show them Bornean pygmy elephants and proboscis monkeys.

But since March 18, Malaysia has closed its international borders to control the Covid-19 pandemic. Europeans make up almost 90% of Kinabatangan’s tourists, so tourism operators like Tapoh lost virtually all their income.

As the months go by, all he is left to do is hope for financial aid from the government.

While this forced hiatus exposes the vulnerability of incomes from ecotourism, it also gives stakeholders an opportunity to build back better.

Stakeholders could use the pause to assess how tourism has been managed in Kinabatangan and the rest of Sabah, and hopefully reposition themselves for a more sustainable future.

What is ecotourism?

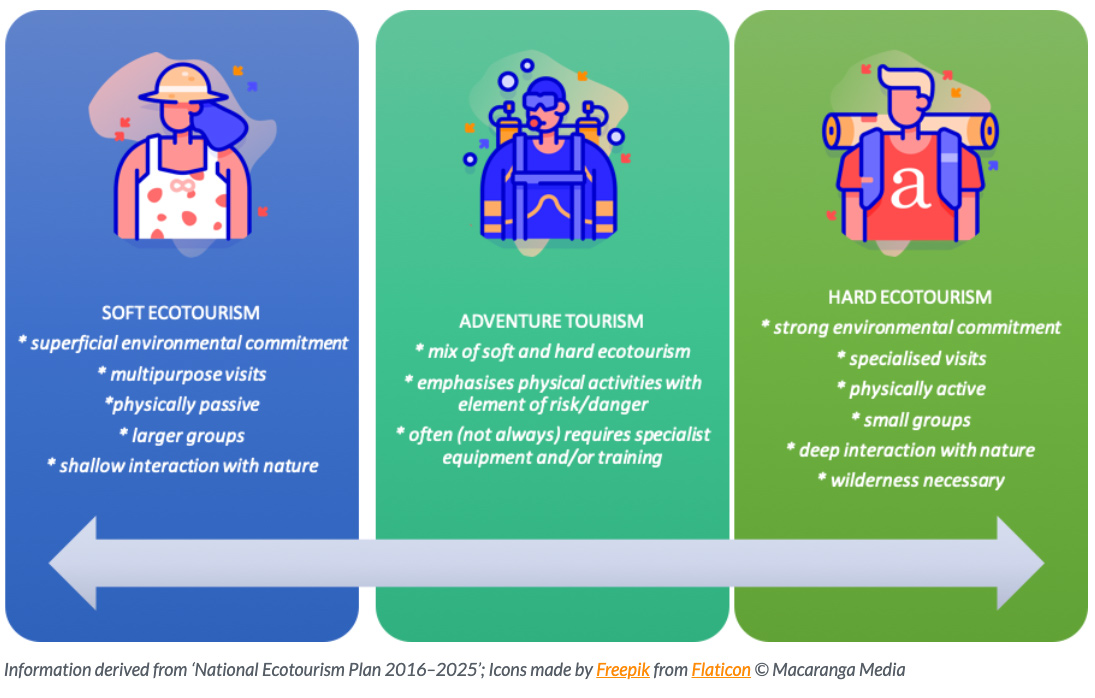

Malaysia’s ‘National Ecotourism Plan 2016-2025’ describes ecotourism as meeting the following criteria:

- Conservation of nature and culture

- Reinvestment of income to maintain quality of resources and conservation

- Ecologically, economically and socioculturally sustainable

- Ethical, demonstrating corporate social responsibility

- Education about biodiversity, habitats, cultures

Ecotourism and nature conservation

The Bornean state has one of the most developed ecotourism sectors in Malaysia, earning it the moniker of the ‘golden goose of ecotourism’.

Virtually every one of Sabah’s tourist attractions falls on the ecotourism spectrum. These include climbing Southeast Asia’s highest mountain, exploring the virgin rainforest and frolicking on sandy-beached islands.

Last year, tourism was the third largest contributor to Sabah’s GDP and supported over 80,000 jobs. Last year also saw a record 4.2 million tourist arrivals, with earnings breaching RM9 billion, an increase of over 8% from the previous year.

These figures have growing through the years until this year.

What’s more, in Sabah, tourism revenue motivates and is linked to the conservation of nature. The state recognises this and a single ministry, the Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Environment, oversees both sectors.

The state has the most protected areas under various legal status in Malaysia. All of these areas have some tourism component (see map).

Totally protected areas cover a quarter of Sabah’s land (1.9 million hectares). The state aims to raise this figure to 30% by 2025.

At the onset of Covid-19, Malaysia’s strict measures to contain the pandemic brought tourism to its knees.

Following the implementation of the Movement Restriction Order (MCO) on March 18, tourist numbers to Sabah plunged by 98% in April and May.

By July, travel agencies had lost 90% in revenue and were asking for government bailouts.

In response, Sabah launched a ‘New Deal’ for economic recovery, including RM22 million to revive the tourism sector; part of this is to subsidise 50% of entry fees to state parks.

The state government also appealed to the federal government for financial aid and more control to revive the industry.

The results of these efforts have yet to be reported. In the meantime, different ecotourism destinations are coping differently to the impact of the pandemic.

Rainforest floodplain

The Lower Kinabatangan in eastern Sabah is Asia’s last forested alluvial plain. But it would have been converted into oil palm plantations if not for lobbying by conservationists, said naturalist and photographer Cede Prudente.

“And tourism played a key role in getting Kinabatangan protected,” he added. “The state could see the benefits for the local people who can earn incomes as tour guides and run lodges.”

Prudente was among the area’s tourism pioneers in the early 1990s. He now runs wildlife photography tours and handles groundwork for mainly foreign video production companies.

Known collectively as the Kinabatangan Corridor of Life, parts of the region has protected status, namely 26,000ha of forests gazetted as wildlife sanctuaries and about 14,000 ha as forest reserves.

These patches occur along the lower 100km of the 560km-long Kinabatangan river. Surrounding the whole are oil palm plantations.

It is a unique location that is home to the so-called Borneo Big Five: proboscis monkeys (Nasalis larvatus), Bornean pygmy elephants (Elephas maximus borneensis), Borneon orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus), rhinoceros hornbills (Buceros rhinoceros) and estuarine crocodile (Crocodylus porosus).

Avid wildlife lovers come from afar to view these animals, river safari-style. Today, tourists’ presence is important for another reason.

“Despite its protected status, hunting and poaching of wildlife in the corridor are threats,” said Prudente. “But then, it’s a nightmare to police the area as it’s a mosaic of forest interconnected with plantations and village lands.”

He said the hunting particularly of Bornean bearded pigs (Sus barbatus) and sambar deer (Rusa unicolor), is done largely by plantation workers.

“However, just by being present, tourists actually act as police to stop the hunting,” he said.

Wildlife in danger?

When tourism shut down during the MCO, there was concern among some conservationists that hunting and poaching had increased. But Sabah Wildlife Department director Augustine Tuuga told Macaranga the department had received no reports of an uptick in this.

Locals certainly have not touched the wildlife.

“That’s the source of our income!” said tour guide Tapoh, who is from the local Orang Sungai indigenous community. He also runs a homestay in Kampung Sukau, a popular tourism hub.

Despite losing all income during the lockdown and experiencing a slow recovery, he averred that he and his community will not hunt or forage in the forest.

Instead, they have returned to their traditional occupation of fishing for food and replacement income.

Tapoh embarked on tourism in 2001. He said he “started from the bottom” in various capacities as a housekeeper, bartender and boatman.

Eight years later, he started his own guided tours and a three-room homestay that is today the only five-star traveller-ranked B&B on Tripadvisor.

“I saw the potential of [tourism],” said Tapoh. He describes tourism as “a big industry in Kinabatangan” and wants the foreign tourists to return; local visitors tend to be day-trippers and don’t spend as much.

However, as the state prepares to reopen its borders to international tourists, Sabah should reconsider its strategy to attract mass tourists, said Alexander Yee, president of the Kinabatangan Corridor of Life Tourism Operators Association (KiTA). KiTA is a conservation-focused group of tourism operators.

“It is pertinent that we don’t lose sight of our positioning as a unique environmental hotspot destination,” he told the Free Malaysia Today news portal.

Instead, to minimise environmental impacts, he called for fewer, high-paying visitors.

The state government had announced in July that it was planning to allow in tourists from Covid-19 safe zones in China, its biggest growing market.

In 2018 and 2019, Chinese tourists made up over 40% of the state’s total visitors. South Koreans made up over 26%.

Specifically for Kinabatangan, Yee, a 25-year tourism veteran, reckoned that the area’s main market, Europe, was unlikely to grow much.

“But if we are aiming to tap the Chinese market, we really need a capacity study done,” he told Macaranga. Kinabatangan tourism already brings in RM100 million a year.

“As it is, all lodges are experiencing full capacity during the European summer; that’s easily 1,000 tourists per day on that river.”

Prudente is also concerned. He thinks that the “peak period is when the government has to come in to control the numbers coming to Kinabatangan”.

“Everyone visits the same tributaries, which are small, crisscrossing each other; it disturbs the animals and distracts the wildlife watching experience.”

Prudente has worked with KiTA to produce guidelines for wildlife watching. It includes keeping a 30m distance between boats and animals and banning any interaction with the creatures. They are also calling for licensing and training specifically for river and wildlife guiding.

“I’d say the standard operating procedures have about 70% buy-in from the guides but it takes time to change mindsets,” said Prudente.

Already, the boatmen-guides themselves try to avoid overcrowding by adjusting their daily trips out. They also take a leaf from the senior guides from the bigger lodges who follow the guidelines strictly.

What now?

Over the years, the Kinabatangan tour operators have built a good reputation for ecotourism. However, until foreign tourists return, the industry seems to be in limbo.

KiTA and individual operators have been working hard on promotions. This includes targeting locals, the only tourists able to visit the region. But this type of hardcore ecotourism does not appear to appeal to most Malaysians and resort operators are suffering.

Tapoh’s homestay has only had one client a month since domestic tourism resumed in July. He cannot wait around any more. He has just flown to Johor to start a temporary job.

“I’ll come back in five or six months. Tourist friends from Russia have made a booking next year,” said Tapoh.

“I hope they can come.”

This is the first of Macaranga’s two-parter on the impact of Covid-19 on ecotourism. In Part 2, we head to the islands, as well as look at opportunities to improve ecotourism overall.

Acknowledgements: Darshana Dinesh Kumar and Cede Prudente contributed research and map-making. Reporting for this story was supported by Internews’ Earth Journalism Network. This is part of Macaranga’s series ‘Taking Stock’ examining how environmental sectors in Malaysia are responding to Covid-19 and a new federal government.