This story was originally published on Malaysian environmental journalism site Macaranga and republished on the Globe as part of a content sharing partnership.

For years now, mass tourism has been impacting the environmental health of coral islands off Sabah’s west coast. Among them is the Mantanani three-island group, located off the northwestern tip of Borneo.

But there are far fewer tourists now as the pandemic stifles travel. Some islanders are using the lull to try new businesses and better manage their environment.

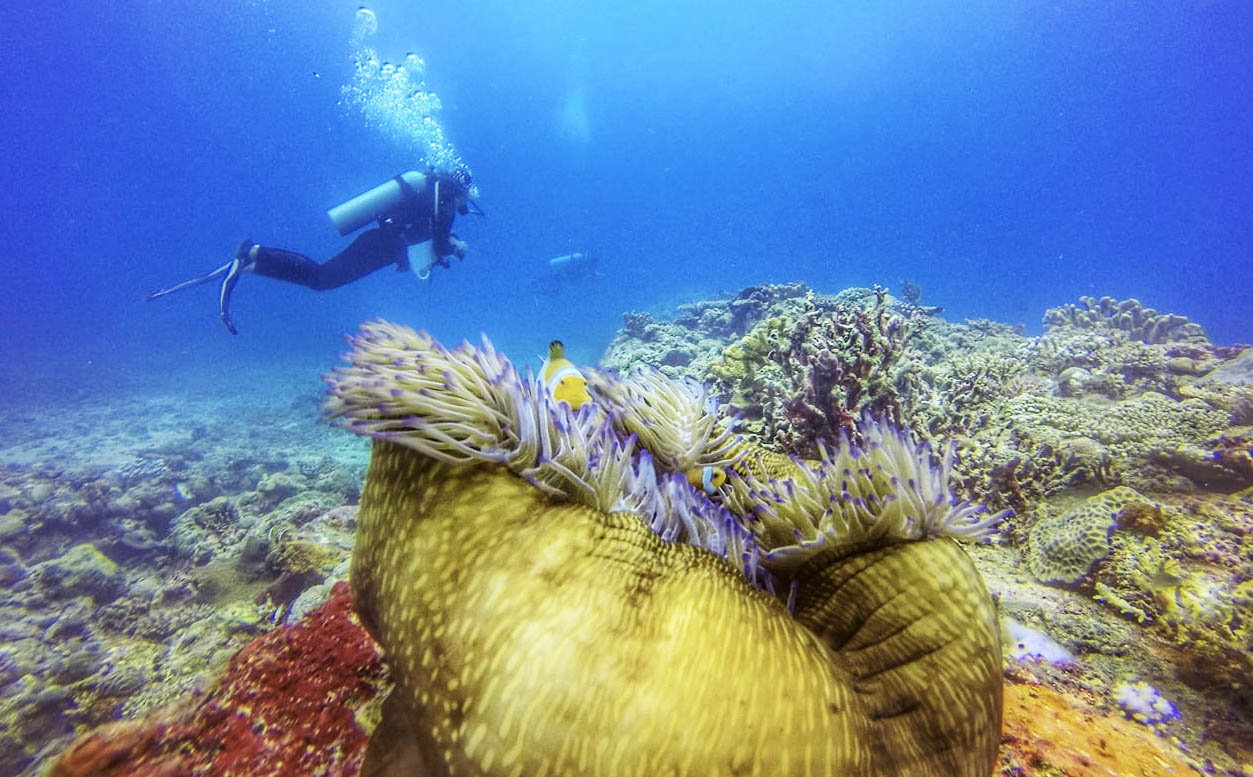

Of tropical-isle idyll, Mantanani is set in shallow azure waters fringed by coral reefs. It is home to a 1,000-strong Bajau Ubian community who are traditionally fishers.

But as far back as a decade ago, overfishing and fish-bombing had degraded the islands’ marine ecosystem, said Adzmin Fatta, the island-based programme manager of NGO Reef Check Malaysia.

As a result, “fishing was no longer providing sufficient income for the island’s households,” he said. A 2013 survey showed that “nearly two thirds [of households] were earning below RM500 [$120] per month.”

Around the same time, tourists started visiting Mantanani.

The islands became so popular that visitor numbers rose from 50 day-trippers in 2011 to 3,000 day-trippers last year, said Adzmin. The majority are day-trippers from China, followed by South Koreans.

The clear seas of Mantanani are a joy to swim in, leading to the explosion in tourist numbers (pics by Homestays Mantanani) and boat operators (pic by Reef Check Malaysia). Pictures are from pre-Covid-19 lockdown.

At the peak of tourist season, the blue waters, especially around the 3km2 main island, are covered by the bobbing bodies of snorkelers overlooked by rows of speedboats.

The tourist boom prompted the islands’ fisherfolk to switch to running boats for holiday-makers, operating homestays and selling handicraft. By last year, around 80% of islanders were earning incomes from tourism.

About half of this group developed their tourism skills with the help of Reef Check’s Cintai Mantanani conservation programme. The objective is sustainable tourism.

Building businesses

Mainah binti Maulana is one of eight local women who approached Reef Check to build their homestay programmes. Last year, after 12 months of tourism skills training, they earned RM50,000 – their first homestay income in five years.

“After we got help, our earnings rose straight away,” said Mainah with pride. She is now the homestay coordinator for the group.

In fact, this year, despite the Movement Control Order (MCO) shuttering tourist arrivals for three months, they have already raked in RM19,000.

But things were bad when the pandemic first shut down tourism in March.

“During the MCO, all my bookings were cancelled,” said Mainah. “We were fully booked for March and April. I was really sad.

“My children lost their jobs in the resorts. So we fished in the nearby waters. We only ate rice and fish every day.”

Worried that the fishing would become “unsustainable if the entire community returns to fishing”, Adzmin said Reef Check organised food aid, for which Mainah, for one, was grateful.

In fact, this continued support from Reef Check has also prompted her to sign up for the NGO’s post-MCO pilot project to diversify incomes.

The so-called economic recovery project aims to overcome the heavy dependency on either tourism or fishing by developing community agricultural, virgin coconut oil production and abalone farming.

Mainah is participating in the coconut component. “I really want to learn how to make the oil, where to market it … It will help generate income.”

Funded by Yayasan Hasanah, the 18-month-long project also has buy-in from another 17 other villagers, including several who have never participated in Reef Check’s programmes.

Adzmin admitted that it was a difficult project to implement, but they are getting help from experienced partners such as a commercial coconut virgin oil producer.

With an eye on the impact of these introduced livelihoods, Adzmin said, “We’re keeping it small-scale, tapping into existing resources like the many coconut trees that are already growing on the island, and wild abalone with which we will be doing in-situ farming in the sea.

“The community farming is for food security.”

Nor has tourism been sidelined, said Adzmin. “We are improving the facilities of homestays, training more guides, and putting together activities and packages – all to encourage tourists to stay longer.

“By the time tourism recovers, say in two years, all services and facilities will be in place.”

Tourism and conservation

Where the marine ecosystem is concerned, tourism has had both positive and negative impacts, according to Reef Check surveys.

On the one hand, the devastating activity of fish bombing has reduced (around 2,000 incidents in 2015 to 200 in 2018) and the population of fish and other sea life has started replenishing, said Adzmin.

On the other hand, with so many tourists pre-MCO, “waste is directly discarded to the sea and polluting reefs,” said Adzmin.

“Unsustainable practices in diving and snorkeling also contribute to the destruction of reefs, such as divers kicking and breaking corals, animal harassment and fish feeding.”

As international borders remain closed, the smaller number of domestic tourists has relieved the stress on the environment

In addition, the locals had been prompted to return to less sustainable fishing to feed the growing number of tourists’ appetite for live seafood.

“This causes over-exploitation of some commercial reef fishes such as grouper and invertebrates such as lobsters and abalone.”

Now, as international borders remain closed, the smaller number of domestic tourists has relieved the stress on the environment.

Sustainable management

However, better tourist management is needed, and is indeed in the offing, with the announcement of the gazetting of Mantanani as a state park by 2023.

Adzmin said Reef Check and the community are working with Sabah Parks towards a long-term sustainable management of the area.

The goal is for Mantanani to be jointly managed by the community and the government so that the locals are empowered, tourism can be run responsibly and the environment is cared for.

Where the bigger picture of ecotourism is concerned, Sabah is already a frontrunner in Malaysia, stated tourism academic-practitioner Prof Dr Amran Hamzah from Universiti Teknologi Malaysia.

“I would say that Sabah is deserving of its status of premier ecotourism destination in the country, not only in terms of price, but service quality and interpretation, story-telling.”

However, he is disappointed that the state’s industry are going for what he calls “a high volume/low yield business model”.

As the lead consultant of Malaysia’s National Ecotourism Plan 2016—2025, Amran has had numerous engagements with the Sabah tourism agencies and industry players, “which were always enlightening”.

He said Sabah was in a prime position to capitalise on its premier label. Besides enhancing interpretation, story-telling and service quality, the state could also build on innovative product development and embracing IT and certification.

“Discerning tourists would not mind paying a premium for a unique and memorable tourist experience,” he said. “But price undercutting, ‘zero cost tours’, illegal guides etc. have impeded Sabah’s tourism industry from moving up the value chain.”

On the whole, mass tourism does not work in protected areas, agreed Surin Suksuwan, Member, IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas.

“There is conflict between having a lot of people be present and maintaining the ecology of the area.”

But mass tourism might work if it were planned properly to be confined to a very tiny part of a park.

“You could for example, allocate a very specific spot like a lookout where you could draw people and keep them there to take their selfies … Only a small percentage would actually venture to explore an area in depth. But it might not work in all contexts.”

However, it is undeniable that “without tourism, many state governments would have been less interested in gazetting a protected area,” he said.

“Chances are, the size of the areas that end up being protected might also have been smaller. Or another site might have been gazetted instead.”

The reason is the loss of income for example, from timber revenue. ”If they are not allowed to touch timber, they need alternatives. Tourism is it.”

This is the second of Macaranga’s two-parter on the impact of Covid-19 on ecotourism. Part 1—When Covid Resets Ecotourism introduces ecotourism in Sabah and zooms in on Kinabatangan.

Acknowledgements: Darshana Dinesh Kumar and Cede Prudente contributed research and map-making. Reporting for this story was supported by Internews’ Earth Journalism Network. This is part of Macaranga‘s series ‘Taking Stock’ examining how environmental sectors in Malaysia are responding to Covid-19 and a new federal government.