To most of the public and the international community, Than Shwe was the malicious and paranoid antagonist to the courageous democracy icon and Nobel laureate Aung San Suu Kyi. Assuming power in a 1992 palace coup, four years after a violent crackdown on anti-government protesters entrenched the country’s status as a global pariah, his two decades in power further immiserated Myanmar’s people, while a cadre of regime tycoons earned billions from lucrative business concessions and the narcotics trade.

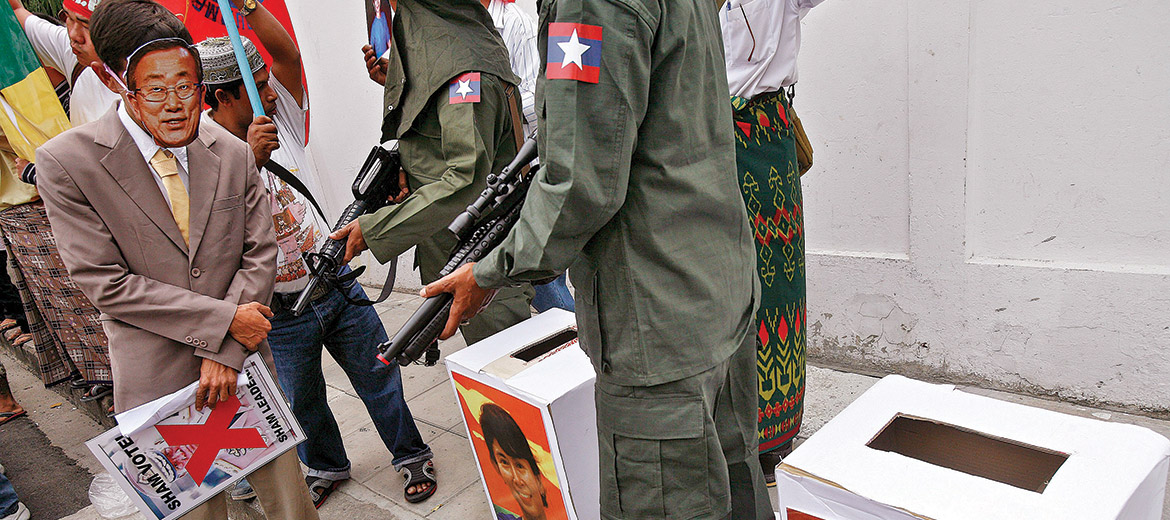

Despite indications that Than Shwe’s health was worsening toward the end of last decade, few in Myanmar’s democratic opposition believed the stream of reports, beginning in earnest around 2008, that the dictator would relinquish power and retire gracefully. Yet after an election in 2010, during which a party of retired generals won a vote widely regarded as rigged, and then the return to constitutional rule the following year, the junta was dissolved and its power ceded to a new national parliament.

In the years that followed, political reform caused a partial liberalisation of Myanmar’s crony economy and reintroduced some of the freedoms curtailed under military rule, culminating in the first free and fair multiparty elections in more than half a century and the rise of Aung San Suu Kyi as the de facto leader of the country.

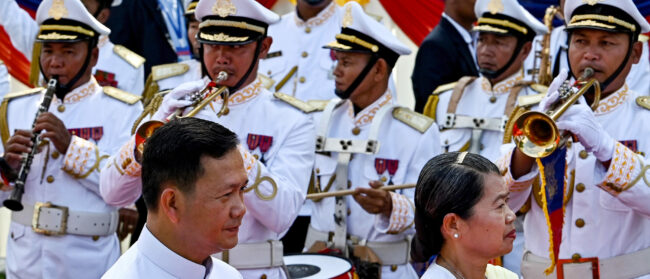

Meanwhile, Than Shwe had decamped to the gigantic compound built for him in Naypyidaw, the regime’s purpose-built capital in the centre of the country, and prepared to live out the remainder of his years as a private citizen. He had negotiated an orderly political transition that allowed him to relinquish power while guaranteeing his protection from the international prosecution demanded by democracy campaigners.

Secluded in his home and protected by a round-the-clock contingent of armed guards, little has been seen or heard of Than Shwe since his apparent retirement.

Many local political analysts, however, refuse to believe he has yielded his political influence altogether. Even now, in many quarters he is regarded as a sinister puppet master; the rare snapshots of his private life that make their way onto social media reliably set off a frenzy of speculation about his lingering power.

Of the few things convincingly documented about his post-junta life, it is certain that Than Shwe maintains an active interest in domestic politics. Htay Oo, a former chairman of the Union Solidarity and Development Party, which took the reins of government after the junta was dissolved, said in 2013 that the former dictator kept up to date with political affairs out of a desire for the country’s democratic transition to be successful.

Other military figures, however, have been unequivocal in dismissing rumours of his continued power. Min Aung Hlaing, who succeeded Than Shwe as military chief, told Radio Free Asia that there was “no influence whatsoever” being exerted by the former leader.

“He’s living peacefully by himself in retirement. I sometimes go to see him to pay my respects on religious occasions, but I do this because he’s the father of the Tatmadaw,” he said, using the Myanmar name for the armed forces. “He gives advice on the betterment of the Tatmadaw, but he won’t say `do this’ or `do that’.”

Any proper accounting of Than Shwe’s finances would likely rank him as one of modern history’s greatest kleptocrats, and his personal fortune appears to remain largely intact. A 2015 Global Witness report into the illicit jade mining industry in Myanmar’s north estimated that holding companies connected to the former dictator’s family had earned $220m the previous year alone.

Yet the opportunities for new revenue streams appear to have diminished with the onset of economic reforms. Prominent local columnist Sithu Aung Myint argued last year that Myanmar’s political leaders no longer thought it necessary to consider the former dictator’s welfare.

Why is it, then, if his political influence truly has evaporated, that so many political leaders continue to pay their respects at Than Shwe’s home?

Aung San Suu Kyi caused a sensation at the end of 2015 when, the month after her National League for Democracy swept that year’s elections, she sat down with the former dictator. At the end of the meeting, Than Shwe inaugurated her as “the future leader of the country” – a stunning turnaround for a man who had attempted to orchestrate her assassination in 2003.

Late last year, Than Shwe received a delegation from the Karen National Union (KNU), an ethnic armed group in Myanmar’s southeast that has spent much of the past seven decades in open conflict with the country’s military. The KNU are the largest participants in a multilateral ceasefire agreement brokered by the government that succeeded the military junta; that Than Shwe would involve himself in ongoing peace negotiations sparked a fresh round of guesswork about his influence on the peace process.

“I wish I knew more than I do,” Kim Jolliffe, a researcher on Myanmar’s ethnic conflicts, told Southeast Asia Globe. “Honestly, I think the main reason [the KNU] met him is the same as why Aung San Suu Kyi did – I think they realise that the power lies there to a large extent… I think they are also trying to win brownie points by showing that they support the government-led process and will be advocates for it.”

Both of these meetings followed an incident that saw the rumours surrounding Than Shwe’s malign influence reach a crescendo. During the final months of the USDP government, a simmering factional conflict between then-president Thein Sein and renowned parliamentary speaker Shwe Mann boiled into the open. A one-time favourite to succeed the dictator, in 2013 Shwe Mann had publicly criticised the legacy of his former boss – something that would have been unthinkable only two years before. At Thein Sein’s behest, Shwe Mann and his allies were purged from their party posts in a dramatic late-night meeting at the USDP’s Naypyidaw headquarters.

At least one media outlet reported claims that Than Shwe’s car had been seen outside the building while these events unfolded. However, this warrants a reasonable degree of scepticism; Shwe Mann had been increasingly collaborating with Aung San Suu Kyi, and now heads her law reform commission. There’s every chance this rapprochement between a career military officer and the junta’s most famous opponent would have been easier to accept for others in the democratic movement if Shwe Mann was cast as a victim of the former dictator’s scheming.

That such rumours continue to gain traction highlights one of the many constants between the junta era and Myanmar’s political transition. Than Shwe was always a reclusive and taciturn figure: even his English-language biographer, human rights activist Benedict Rogers, was unable to determine the dictator’s true age or birthplace. The mystery of the remote and almost universally reviled former leader has been compounded by the more open climate since the end of the junta, while a freer press and almost universal access to the internet has led to greater scrutiny of other public officials.

With the former dictator’s long shadow still casting a pall over the country’s politics, Myanmar military historian Mary Callahan told Southeast Asia Globe it was natural that belief in his influence would continue.

“I think, when you see something that can’t be explained or is mysterious to people,” she said, “that’s when you start hearing Than Shwe’s name.”