Fly River, western Papua New Guinea. The chocolate brown water not only bears its colour due to high concentration levels of humus, it is also the result of centuries of floating timber transports and decades of spilled waste from the Ok Tedi mine mill, situated near the river’s source.

The dense forestry along the western riverbank glares into a political no-man’s-land. The river cuts the border between where Papua New Guinea ends, and West Papua begins. On both sides of the river, vast jungle corridors lead into villages populated by people who fled the Indonesian military, now living lives either as internally displaced people in West Papua, or as forgotten refugees in Papua New Guinea. They are neither fully integrated to the everyday life tied to the Fly river, nor able to return home – their home, in fact, is not even allowed to exist under Indonesian law.

Since December 2018, West Papua has been a war zone where unarmed civilians die behind closed doors and 40,000-odd IDPs are dependent on emergency aid from local churches, in what is a terra incognita for independent journalists and international aid organisations. Calls for the Indonesian government in Jakarta to hand the West Papuan people its long-awaited referendum on independence are met by warfare, mass arrests and extrajudicial killings. It was a promise made to the West Papuan people by the United Nations in the early 1960s – a promise thus far never granted, although never forgotten.

2020 – the year of Covid-19 – has converted into a decisive eleventh hour, where Indonesia’s six-decade-long rule has been sincerely questioned and openly threatened as among some of the most ardent calls for West Papuan independence to date have arisen. On 1 December, The United Liberation Movement for West Papua (ULMWP) announced the formation of a “Provisional Government,” led by President Benny Wenda, a former political prisoner who has lived in exile in London for many years.

“This is about showing the world that the ULMWP is ready to take over the country, and represents a viable alternative to Indonesian rule,” Benny Wenda told the Globe in a recent interview.

This manner of rule by Indonesia has led to grim stories told and retold in vivid detail by inhabitants of the village Dome, a West Papuan settlement on the Fly River. Bomb raids and large-scale military operations, followed by long and exhausting treks through thick jungle to temporary safety in the vicinity of Papua New Guinea. A protracted existence, they await the arrival of an independent West Papua, liberated from Indonesian sovereignty that has held their lives, forests, mountains and rivers hostage since the early 1960s.

West Papua is Indonesia’s colonised easternmost corner – where Southeast Asia ends, and the South Pacific begins. This is also one of Indonesia’s poorest and most undeveloped corners, despite sitting on top of one of the planet’s most lucrative gold and copper reserves.

It was no coincidence that the recent announcement of a provisional government occurred on 1 December. The date marks the anniversary of the 1961 ceremonial opening of the West Papuan parliament in Jayapura, when the western half of New Guinea was underway to broker independence from the Netherlands.

The dawn of a nation was near, in a time of global decolonisation.

But, far away from the colonial masses in the UN headquarters in New York, the Dutch colonial power and the Indonesian government brokered a deal in 1962, “The New York Agreement”, which paved the way for Indonesian rule of west New Guinea, awaiting a UN-led referendum. This resulted in the “Act of Free Choice” in 1969 – a “referendum” in West Papua in which only a little over 1,000 selected elders were allowed to participate.

The result, not surprisingly, was in favour of Indonesian integration.

“Many who were chosen to cast their votes have explained that they were forced to ‘vote’ to become a part of Indonesia – literally at gunpoint. All this occurred with the silent complicity of the UN,” said Jason MacLeod, an Australian academic who has taught civil resistance at the University of Sydney and author of Merdeka and Morning Star.

With more than 20 years of experience of social work in West Papua, he quite literally stumbled upon the knowledge of the conflict along a muddy road off the beaten track. Here, he realised the David versus Goliath-like conflict, meeting a man who told him about Indonesian military operations in the Baliem Valley – something never mentioned in Australian textbooks.

The Indonesian military had come, bombarded and cleared villages, finally dropping unarmed civilians into the rivers, which was soon coloured in red.

“Tell the world my story,” the man pleaded.

Two-headed response

The Indonesian government, led by President Joko Widodo, has responded to the ULMWPs demand for an UN-instigated referendum on independence – something Kosovo, South Sudan, and previously Indonesian-occupied East Timor have been awarded in the past two decades – with political indifference and military escalation in recent months.

“Two things have happened as a result of the proclamation of a provisional West Papuan government,” said Socratez Yoman, president of the Fellowship of Baptist Churches of West Papua. “First, Indonesia has increased its number of troops, and second, West Papua Council of Churches endorses the announcement and welcomes the media attention it has brought to the conflict.”

Jacob Rumbiak, the spokesperson for the provisional government, who for many years has lived in exile, believes the overwhelming violence and repression is a blatant attempt to erase future West Papuan leaders.

“We’ve never witnessed this amount of violence and repression as of now,” he warned.

We met children who told us they had to flee helicopter attacks while they attended class. They left everything behind and walked for days before reaching safety in Wamena

West Papua’s current conflict and humanitarian crisis erupted in December 2018 in Nduga regency in the central highlands. Some 20-odd workers of Istaka Kaya – a semi state-controlled construction company, constructing bridges as part of Indonesia’s mega infrastructure project “Trans-Papua” – were caught photographing a guerilla assembly, where the forbidden Morning Star flag was raised. They were executed shortly afterwards, while an Indonesian soldier was also killed in the following commotion.

The Indonesian military moved quickly to retaliate and launched large-scale operations in Nduga. Villages were bombed and burned, and civilians were killed. Over 40,000 civilians sought refuge in the mountains and vast forests. Many have since resided in temporary refugee camps, not yet recognised as internally displaced people by the Indonesian state, which does not acknowledge the conflict as a “conflict” at all.

“Many who died in conflict died alone, without anyone by their side in the end,” Theo Hesegem, director of Frontline Defenders, told the Globe.

Hesegem belongs to an already endangered species, running the risk to soon be eradicated in West Papua: human rights workers with knowledge of the conflict and author of close-to-the-ground reports, straight from the conflict zones. Tireless travels paid for from his own pocket take him to forgotten spots in the central highlands, where he interviews, listens and documents human rights violations.

Hesegem’s reports are often detailed and impressive documents, but his emergency calls from a desolated people seldom break through the political dome surrounding West Papua, imposed by Indonesian authorities. More than 200 politically motivated arrests were made by Indonesian authorities in 2019-20, of which 57 await treason trials. Far away from the demonstrations in the streets of urban areas, at least 243 civilian lives were spilled in Indonesia’s military operation in Nduga.

“The situation in Nduga remains unsafe, it’s still chaotic and utterly worrisome,” he said.

One of few outsiders with first-hand knowledge of the West Papuan IDPs dire conditions is Peter Prove, director of the World Council of Churches’ Commission of the Churches on International Affairs. What he witnessed in February 2019 in Wamena, eastern West Papua, was nothing he had ever seen before.

“We met children who told us they had to flee helicopter attacks while they attended class. They left everything behind and walked for days before reaching safety in Wamena. Along the road they saw death and many of the children were alone, without their families,” he said.

I can’t think of any other place where the international community hasn’t been present. I found that extraordinary

The WCC commission were also introduced to cannisters used by the Indonesian military. Chemical weapons, which the Indonesian government denies were used during the “security operation”.

“We witnessed wounds which looked like the result of usage of white phosphorous,” said Prove.

Perhaps most striking was the fact that hundreds of young people, displaced by conflict, were taken care of by the local church community, without any coordinated international response.

“I can’t think of any other place where the international community hasn’t been present. I found that extraordinary,” said Prove.

The perfect storm

Indonesia’s military operations in Nduga laid the foundation of a perfect storm, one which not even President Widodo seems capable of controlling.

Besides repelling low-intensity guerilla warfare against isolated military posts and sneak-attacks against Freeport-McMoRan’s gold and copper mining operations in Timika – the mine is Indonesia’s single most important tax income source – the Jakarta government continues to expand its military presence without much investment in dialogue.

The results are mass arrests of peaceful independence activists, the crackdown on social movements and the killings of religious leaders – among them 63-year-old Pastor Yeremia Zanambani, who was killed while feeding his pigs in Intan Jaya regency.

“Indonesian officials at the highest levels have made serious threats against Benny Wenda, the ULMWP and their members and supporters in West Papua,” says Jennifer Robinson, barrister at Doughty Street Chambers in London and spokesperson for International Lawyers for West Papua, in a statement.

Ever since the 1960s, Indonesia has shown its intention to hold on to the western part of New Guinea at all costs. Children sing the patriotic song From Sabang to Merauke, cementing in the next generation the narrative justifying Indonesia’s annexation of West Papua. This annexation is motivated by fiscal dependence on the mining revenues at the Freeport mine, oil reserves in West Papuan waters, the forests waiting to be cleared and sold and making way for palm oil plantations.

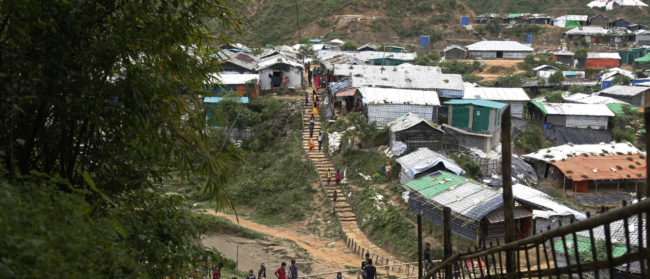

In the village of Dome, along Fly River’s western bank, many West Papuans share their experiences, losses and nightmares – their reports punctuated with exacerbation.

“What good will it do? Foreign reporters have been here before, without it leading anywhere,” they said. “So why talk to you?”

Dome’s oldest man believes he is well over one hundred years and sees poorly on both eyes. He has lived a long life, once overseeing the Dutch colonial administration’s missionaries, sent along the rivers to inform the “savages” about the benefits of salvation and civilisation.

But this salvation has arrived in the shape of Indonesian colonialism of palm oil plantations, open-pit gold and copper mines, disease, persecution, murder and political repression.

“West Papuans remain victims of colonial ideas and are being treated like savages in need of development and capitalism,” Sophie Chao, anthropologist and ethnographer at the School of Philosophical and Historical Inquiry, told the Globe.

The UN’s silent support for the 1960s Indonesian annexation and ongoing exploitation slammed shut the door to the outside world in the face of the West Papuan people. A betrayal that, per Benny Wenda, pours the responsibility of “a legitimate chance for freedom” on the shoulders of the global community in general – and the UN in particular.

“The UN knows what is really happening in West Papua today, the UN knows that the West Papuan people don’t wish to be part of Indonesia,” the provisional president of West Papua said. “West Papua is the cancer at the heart of the United Nations, and this issue is not going away until our right to self-determination is granted through a referendum on independence.”

Klas Lundström is an investigative reporter who focuses on environmental issues, mining production and indigenous people and their place in a globalized village. He is the author of several books on East Timor, Indonesia and West Papua (co-authored with Ivar Andersen).