For the first time in at least six years, voters in Thailand will be heading to the polls this weekend for nationwide provincial elections.

National politics since June have been mostly dominated by the ongoing pro-democracy protests that have pushed for sweeping government reforms while shattering taboos around addressing the power of the monarchy. Against that tense background, the 20 December provincial elections will make an opportunity to test the waters of change, shifting discussion out of Bangkok and into the local arena to see how new ideas fare with voters outside the capital.

From northeastern Thailand, Ubon Ratchathani University political science professor Patawee Chotanan told the Globe the absence of provincial elections for more than half a decade has eroded accountability among leaders in local areas.

“This time the elections are very important. We haven’t had provincial elections in six years. In some places, it’s been eight years,” explained Patawee, who studies local administration. “What happened [during that time] is that the accountability between the elected leader and the people has deteriorated.”

The last Provincial Administration Organization (PAO) election was held in 2012, with all local elections suspended soon after the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) staged the 2014 military coup that displaced Yingluck Shinawatra’s government and seized power.

In the past, local elections were not of high interest, but this election comes at a time when Thailand’s political divides are running deeper than ever. Mark Cogan, a former UNDP communications specialist in Thailand, now peace and conflict studies professor at Kansai Gaidai University in Osaka, Japan, notes the importance of this year’s provincial elections.

“This election is a test of whether or not the [Progressive Movement] or any sort of new movement can influence elections that have been dominated by patronage networks and by old familial connections,” said Cogan.

A major new player in these elections is the Progessive Movement, born from the remnants of the Future Forward party (FFP), a rising opposition group dissolved under controversial circumstances by the Constitutional Court in February.

Leaders of the FFP, Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit along with Piyabutr Saengkanokkul and Pannika Wanich, now banned from holding public office for 10 years, reformed as the Progressive Movement to continue the FFP’s agenda and campaign for local elections throughout the country.

For this upcoming election, the Progressive Movement has candidates in 42 provinces, campaigning under the slogan “changing Thailand starts at home”.

“[The Progressive Movement] have advocated decentralisation, but they’re way way behind the curve in terms of their influence and their ability to undermine the influence of local political networks and dynasties,” said Cogan. “[Thai politics] is dominated by these local political dynasties that have their sort of tentacles all over the local communities.”

A high voter turnout is expected at this weekend’s polls, with the National Institute of Development Administration survey finding that over 80% of voters say they will exercise their ballot on December 20, compared to the 60-70% in 2012.

The competition is fierce for PAO chief executive positions, with this the first time that all 76 provinces in Thailand are holding provincial elections at the same time. There are 336 candidates running for provincial chief executive and 8,186 for members of the PAO council in this year’s contest. Of a total local government budget of $2.7 billion, operating budgets for each PAO range from $3.9 million to $77 million per year, depending on the province.

The provincial election will also be the first time that voters aged between 18-26 – the predominant demographic at this year’s ongoing pro-democracy protests – will be able to exercise their right to vote for the provincial administration. Young voters are an important support base for the Progressive Movement and will test if they are able to generate the same level of enthusiasm that their predecessor, Future Forward, generated among youth at the 2019 national election.

“People haven’t voted in a very long time and I think they’re itching to do so,” said Cogan.

Across Thailand, campaigning has started as party trucks roam, posters fill the streets, and leaflets are snuggled into gates of homes across the country. This time around, social media, especially Facebook, is also a major platform for campaigning.

“They’ve started campaigning. It’s the week of the elections now so I expect them to campaign a lot this week. Campaigning cars pass our shop all the time,” said Gob, a resident in Nonthaburi province, just north of Bangkok.

In local politics, there really is a mafia system that exists. Even in Nonthaburi, an area that is already quite developed. We don’t want local politics to be tied to political elites or oligarchs

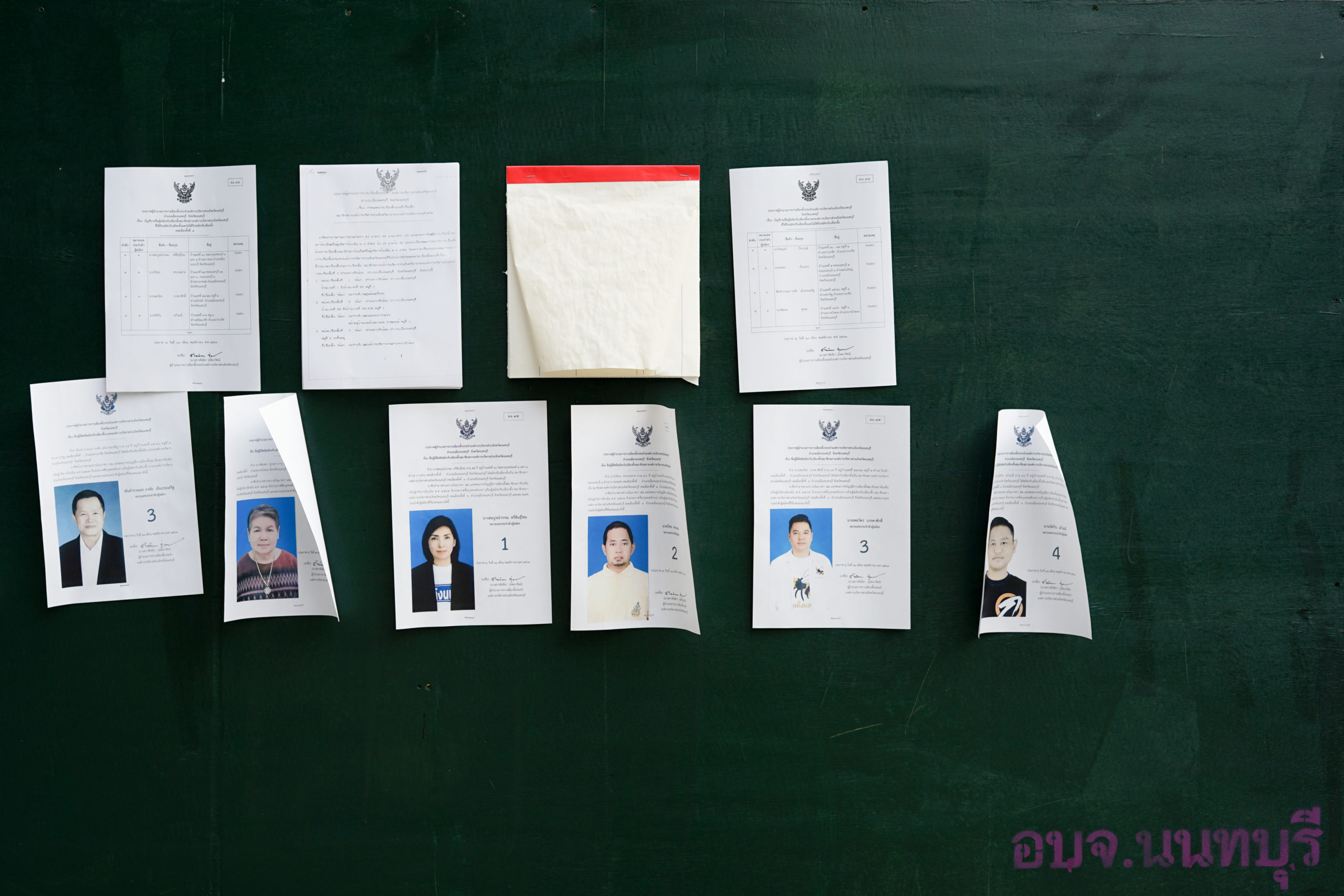

In Nonthaburi, there are three main candidates for the provincial chief executive – Paiboon Kitworawut with the Progressive Movement, Chalong Riewraeng, and Thongchai Yenprasert, previously a three-time PAO chief winner.

For the Progressive Movement’s Kitworawut, a candidate for provincial chief in Nonthaburi, he hopes to bring a new generation to solve local problems.

“In local politics, there really is a mafia system that exists. Even in Nonthaburi, an area that is already quite developed,” said Paiboon, answering questions via Facebook live while on a boat ride through Nonthaburi. “We don’t want local politics to be tied to political elites or oligarchs.”

While local politics is a different ball game to national politics, Cogan notes that entrenched networks of patronage transcend and connect the two in Thailand.

“It’s [the election] a test of the strength of these old networks. It’s local people connected to local political families and these are the nuts and bolts of Thai politics. Political families connected to local people, and the local people come out to canvass for them, and then they canvass for the national politicians.”

As 2020 nears a close with still-raging demonstrations that have pushed boundaries in Thailand’s political discussion, it is yet to be seen if that change will be reflected in the results of these provincial elections.

A loss of faith in the country’s political institutions, from the monarchy to the government, has been among the largest motivating factors drawing people to rally on the streets of the Thai capital in recent months. For Cogan, the return of local elections could go some way to repairing that.

“If you enable local institutions and local officials to make decisions without the input of a centralised bureaucracy or a centralised ministry, you empower local officials, and trust theoretically can be restored,” he said. “Decentralisation will promote local decision making and it speeds up the delivery of essential social services. It shifts the centres of political power, or some of it, to local governments.”

Local politics is an important school that trains citizens to become active citizens and to exercise their rights

For Patawee, local politics is a reflection of the wider health of Thai democracy.

“If national politics is good, local politics will follow and will also be good,” said Patawee. “But also, if local politics is good, it’s an important mechanism to drive national politics to also be good because they bring local issues, summarise the problems, and present it to their local leader. Local politics is an important school that trains citizens to become active citizens and to exercise their rights.”

Thailand’s development is highly centralised in Bangkok, with the capital accounting for over 40% of national GDP. But central to provincial elections is the opportunity for the local needs to be heard and met, with candidates campaigning on specific problems to the area, given the authority and resources to resolve them, and then held accountable.

This, Patawee argues, is key to remedying Thailand’s lopsided development and the growth of provincial areas.

“If there is decentralisation, local leaders have the authority and resources to develop their local area, then it will develop further because they want to maintain their voter base,” said Patawee. “But in the past six years, that process has been frozen.”

So as the provincial elections go ahead this weekend, in the eyes of Patawee this election is an opportunity to restore the roots of local democracy, torn up six years ago with the military coup.

“The PAO has turned to decorative wood – like a Bonsai tree, its growth is determined by the [central government] and it cannot grow much further than that,” said Patawee. “This election is important as a point to determine what will happen next with local politics.”