Each came for a reason and died taking a chance. They were veterans and amateurs, staff shooters and independents, gun-toters and pacifists. One never sold a photograph; two had won Pulitzer prizes. Some were buried with honours and mourned by nations; others simply disappeared. They came from around the globe to become the greatest assemblage of photojournalists in history.

If they’d all been gathered together on the Continental Palace’s terrace, watching beautiful women in ao dais glide by, they wouldn’t have been able to speak one another’s mother tongue. But in the field, in the mud and blood and monsoon, they found a common language through the lens.

Some stayed on for the glory, the money, the thrill. Others returned, again and again, because it was the place to be. North Vietnamese and Viet Cong shooters didn’t have a chance: their orders said stay until victory or death. All lived for the next picture; it could be the best one of all.

‘Stick close to him,’ one youngster would whisper to another, pointing to François Sully or Larry Burrows or Henri Huet. ‘He’s lucky. He’ll keep you alive‘

“Got another Time cover; I think it’s the eighth picture I’ve had in Time and Newsweek since July,” the American Dana Stone said into a tape recorder in 1967. “That’s a lot; that’s more than I could’ve gotten anywhere else in the world, so I guess it pays off.”

“If you hear that I’m coming back soon, forget it,” Oliver “Ollie” Newton wrote home to America shortly after his arrival in what was then called Saigon. “I like this place. It’s really great over here for a newspaperman.” Like those who had arrived before him and those who would come after his death in a helicopter crash in 1969, Noonan relished the camaraderie and the competition.

Rookie photographers, like second lieutenants, had a life expectancy of 15 minutes. Some survived just long enough for colleagues to learn their names. Others were not who they seemed. After the Englishman James Gill was killed in Vietnam in 1972, friends were sent to his apartment to pack up his possessions and discovered that he was a deserter from the British marines named James Cattell.

Some photographers carried guns, others smoked opium, many drank. Some spent all their money when they got it; a few got rich off spoils. Some won every major award in photojournalism; some barely sold a single photo. To live in a war zone is to live on top of the world; friendships are closer, love deeper, fear stronger. Vietnam was not a cautionary tale. All that mattered was the work and staying alive to get it out.

Some survived only weeks. Those who lived long enough became legends. Old Vietnam hands were pied pipers to newcomers. Cults sprung up around them. “Stick close to him,” one youngster would whisper to another, pointing to François Sully or Larry Burrows or Henri Huet. “He’s lucky. He’ll keep you alive.” Everybody knew it was nonsense, but …

Longevity in war isn’t just luck. Survivors are smart, superstitious, careful. Sometimes that still isn’t enough.

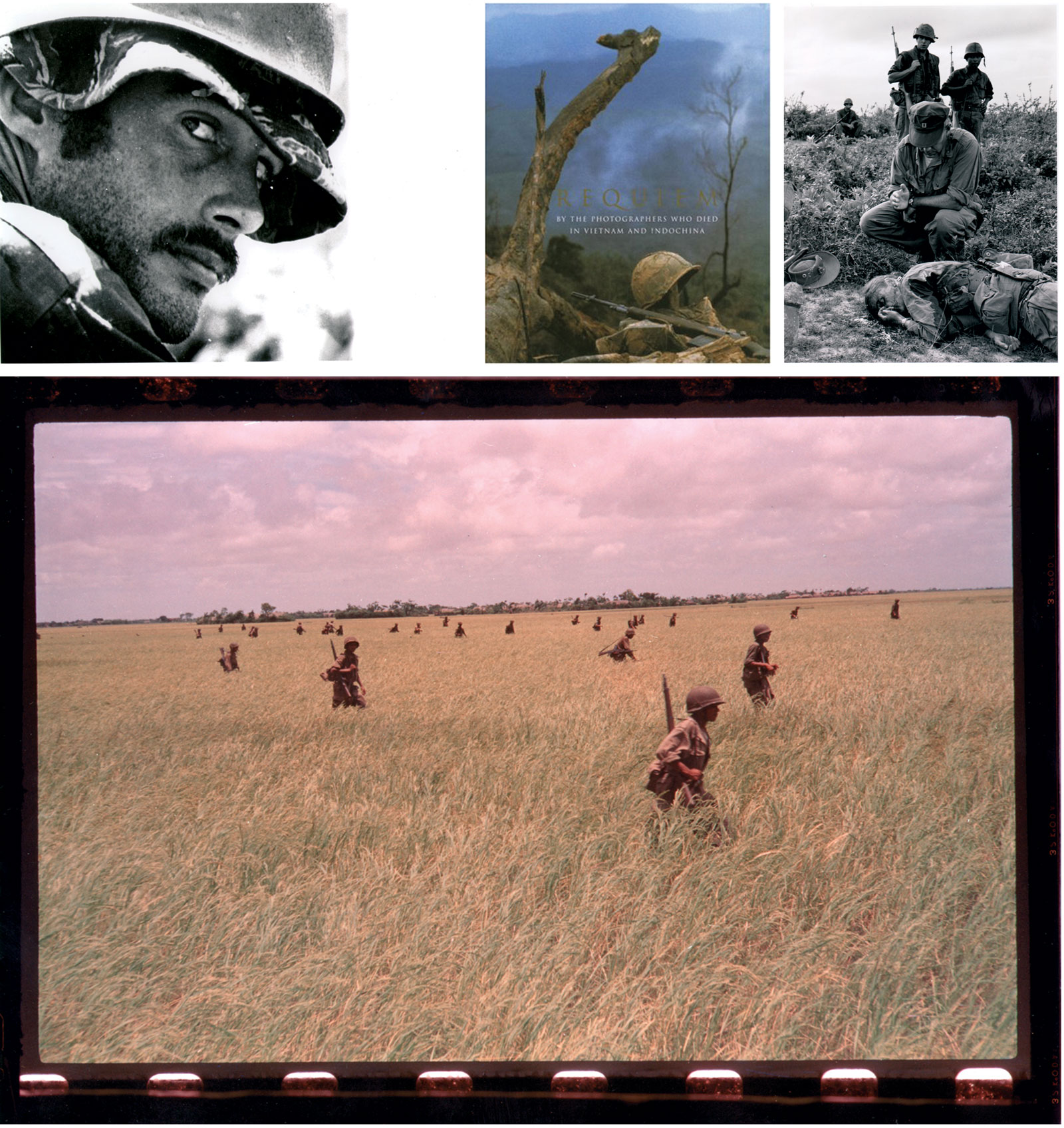

Robert Capa: His last colour film (bottom) was retrieved from his camera after he stepped on a mine. Sean Flynn: Top far left, who disappeared in Cambodia, inspired Page and Faas to produce Requiem. Dickey Chapelle (top far right) receives the last rites after she was killed by a mine

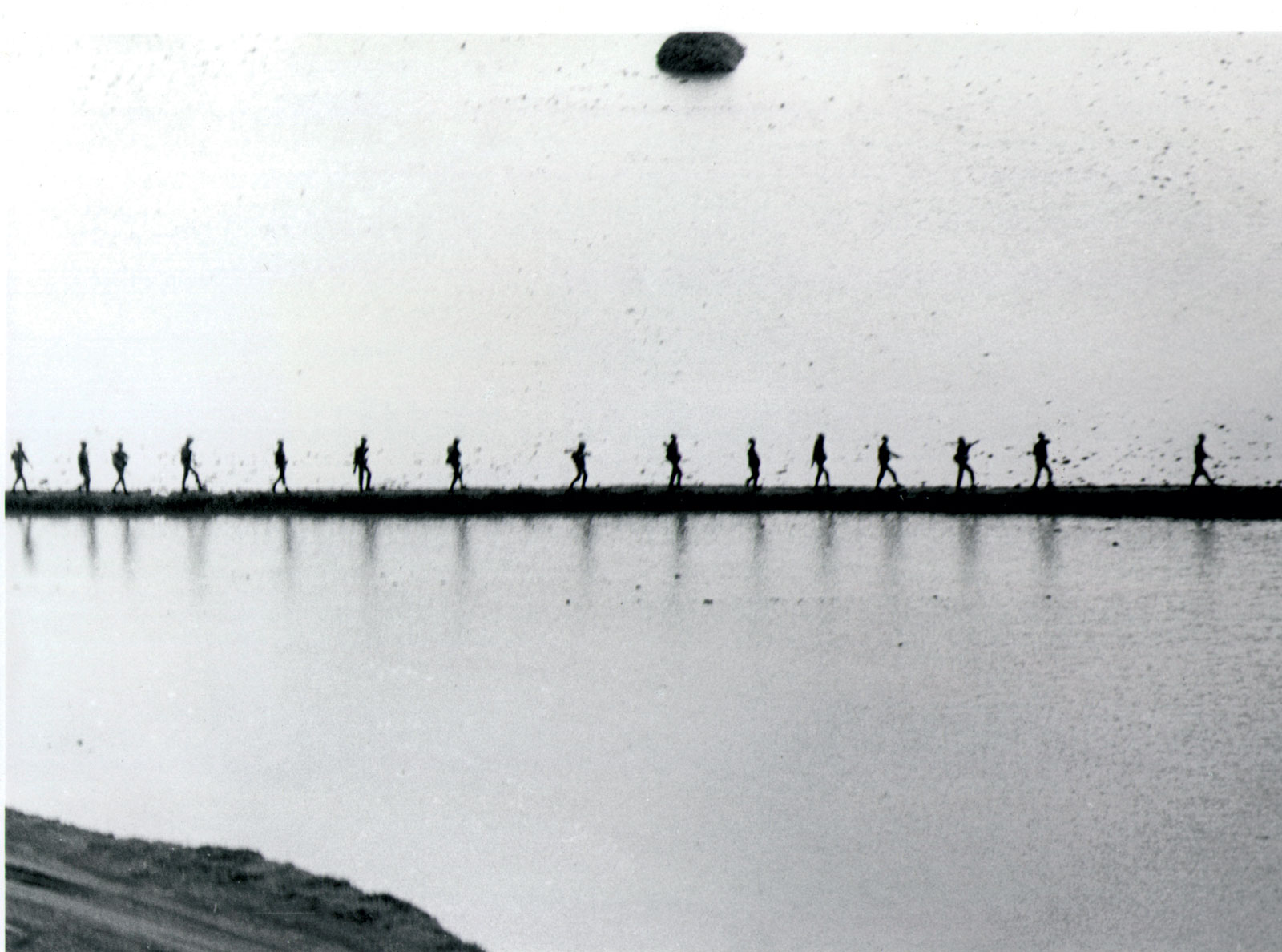

Robert Capa epitomised the experienced professional in Vietnam. He was covering his fifth war when he set out with French troops in 1954 to photograph a story in the Red River delta near Hanoi. He spent the day in late May photographing rice paddies surrounded by tanks. Routine. There was a false step. Only the legend remains.

Everette Dixie Reese, a Texan working as a freelancer and for the US Information Agency, covered Dien Bien Phu and the ceasefire following France’s defeat. He captured rare images of peace between the two Indochina wars.

His landscapes reveal rainforests before defoliants, rice fields without B-52 craters, marketplaces free of barbed wire. Some of his favourite shots were of Cambodia’s Elephant Brigade and the Laotian royal family.

A civilian pilot was flying Reese above Saigon for aerials of an attempted coup when their tiny L-5 Stinson was shot down on April 29, 1955.

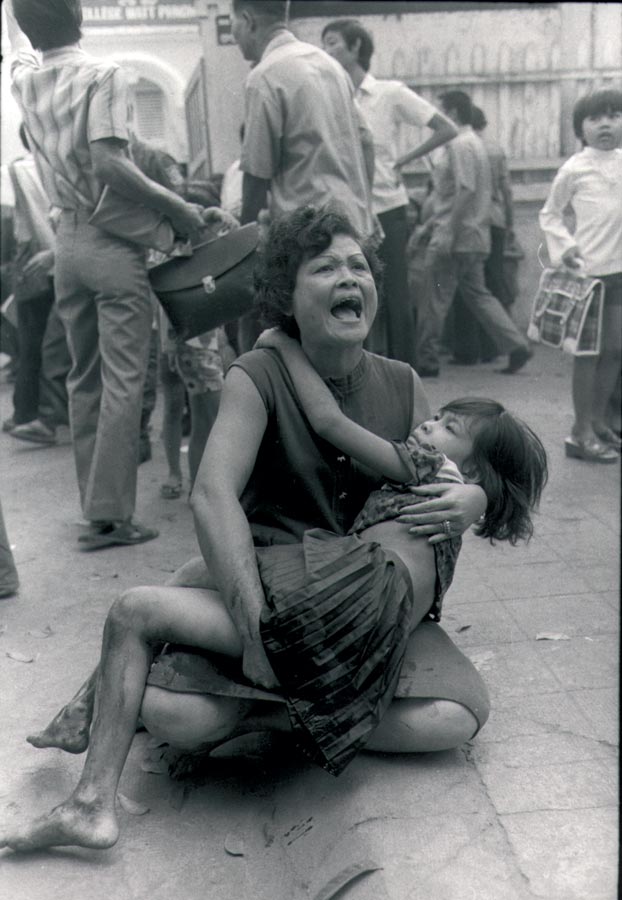

Civilian cameramen, sound men, correspondents for radio, television and newspapers, special writers for magazines, even newsreel cameramen with the French in the first Indochina war – members of every journalistic medium lost their lives from 1945 to 1975. Death was not discriminatory or selective.

That year [1970] 24 Western journalists died or disappeared in Cambodia

Cameraman Terry Khoo and his replacement, Sam Kai Faye decided, on the spur of the moment, to leave Hue on the morning of July 20, 1972. Engaged to be married in a week, Khoo was leaving Vietnam the next day, after seven years, to take a plum job in ABC News’s Bonn bureau in Germany. Faye, a veteran, had just returned to Vietnam for another tour. Both cameramen already were celebrated still photographers; Faye had won the British Commonwealth photo contest twice and Khoo’s photos were printed in Asia.

A sniper shot Faye first. Khoo stayed with him, calling out “I’m okay” to a soundman who escaped. A sniper then killed Khoo. Their bodies weren’t recovered for several days. A Vietnamese army cameraman was killed with them in the same open field near Quang Tri, one of dozens of military photographers who perished during the war.

Some photographers were highly educated, even scholars; others came without formal schooling to find an education in life.

Kyoichi Sawada was an orphan who discovered photography as a clerk in a camera shop. His UPI bosses in Tokyo wouldn’t assign him to Vietnam, so he went there on vacation; his pictures from that trip landed him a permanent staff job in Vietnam, where he won the 1966 Pulitzer prize for news photography.

A cautious man who always wore a helmet, he reluctantly agreed in 1970 to introduce an eager new UPI bureau chief to Cambodia’s Route 2. Twenty six miles out of Phnom Penh both were shot in their rented blue Datsun. That year 24 Western journalists died or disappeared in Cambodia.

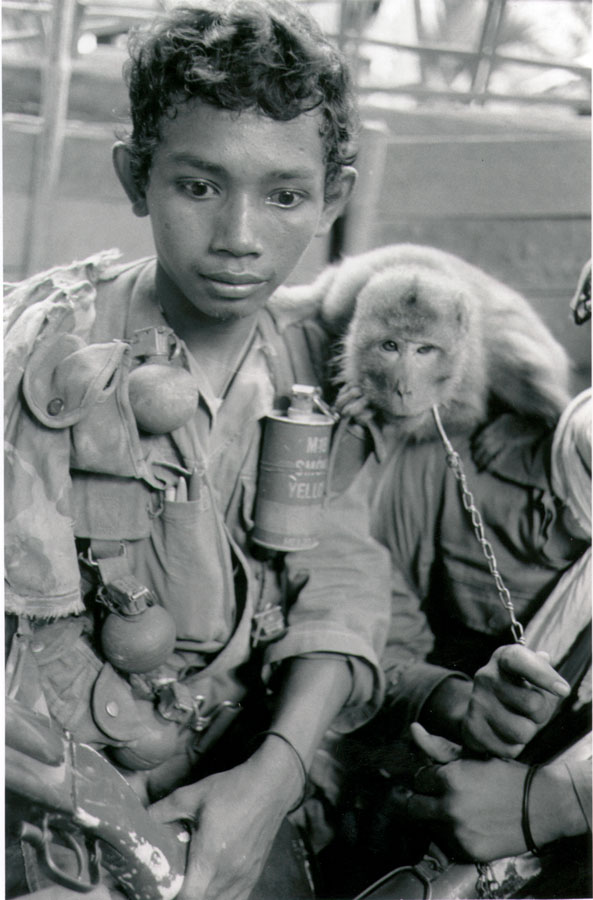

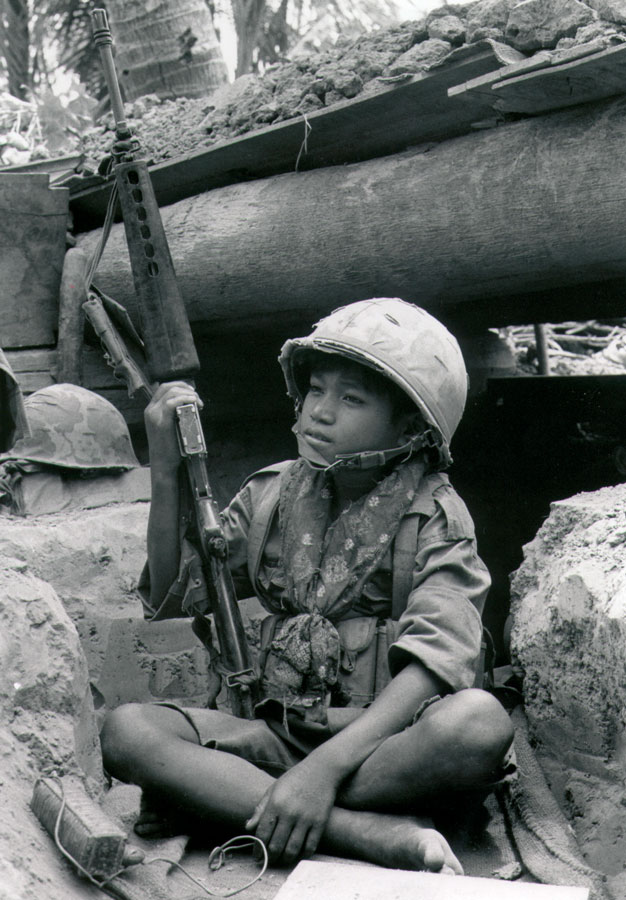

Horrified: a child soldier with his only friend. Children were often included on both sides in the war because they were easy to control and eager to become heroes

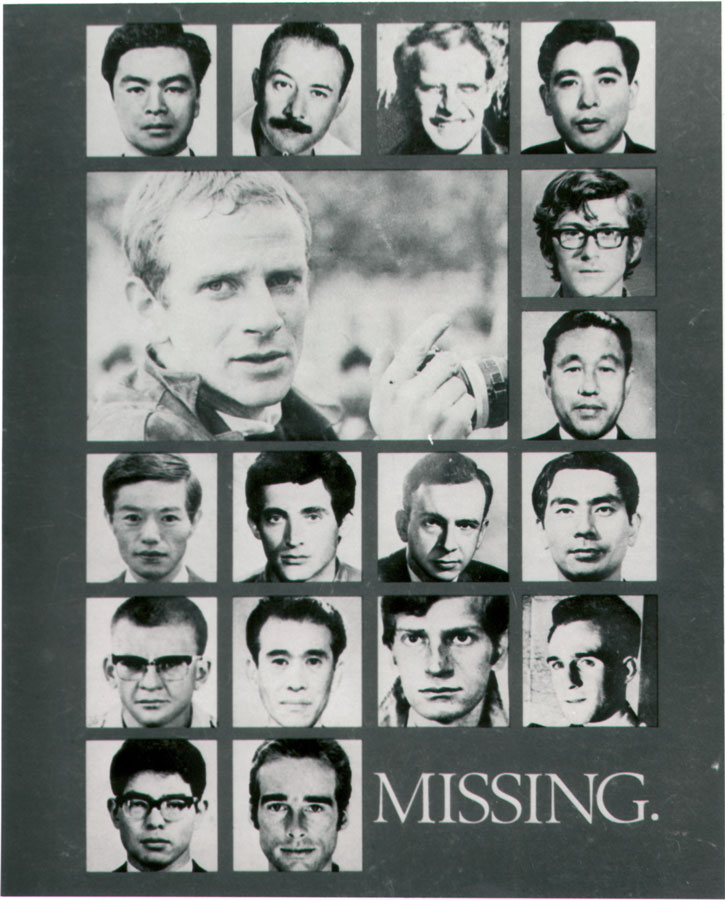

The Missing

Seventeen journalists went missing in Cambodia over the course of only two months during 1970, after the coup d’etat that ousted the government of Prince Norodom Sihanouk. Many searched for them; everybody hoped they would return. There but for the grace of God was the fate of everyone who covered the conflict. But in a war with few clearly delineated frontlines, final sightings of many of them were the last fleeting memories people had as they went into battle with their cameras and notebooks. Many of them disappeared on their way to Kampot and Takeo and all efforts by the press corps to locate them were to no avail.

From top left to bottom right: Takeshi Yanagisawa (Japan), Gilles Caroon (France), Yujiro Takagi (Japan), Dieter Bellendorf (German), Teruo Nakajima (Japan), Roger Colne (France), Claude Arpin (France), Tomoharu Ishii (Japan), Sean Flynn (USA), Georg Gensluckner (Austria), Welles Hangen (USA), Guy Hannoteaux (France), Akira Kusaka (Japan), Dana Stone (USA), Kojiro Sakai (Japan), Yoshihiko Waku (Japan), Willy Mettler (Switzerland).

Because they spoke the language, knew the terrain, had the contacts and worked cheap, Vietnamese photographers were the backbone of coverage for the Western news organisations.

Huynh Thanh My set the standard for the rest of his countrymen, including his younger brother. After Thanh My was killed in 1965, his brother Huynh Cong Ut hung around the AP office begging to be taught how to take pictures. Eventually the kid, dubbed Nick by the AP staff, was hired full time by the wire service. In 1972, Nick Ut took the Pulitzer prize-winning photo of the little girl burned by napalm and running down a road.

In Ho Chi Minh’s army, photographers were soldiers first, then journalists. They carried light arms at most times, used rocket launchers, mortars and threw grenades and often had to fight their way out of tight spots. They wore uniforms and were often seen with AK-47s slung over their shoulders and a camera around their necks. Two of the 72 communist photographer-correspondents killed in the war were women, Le Thi Nang and Ngoc Huong.

The circle closed. A war that began with the death of the French photographers Raymond Martinoff and Jean Peraud in 1954 ended with the loss of their countryman Michel Laurent on the eve of the end of the war.

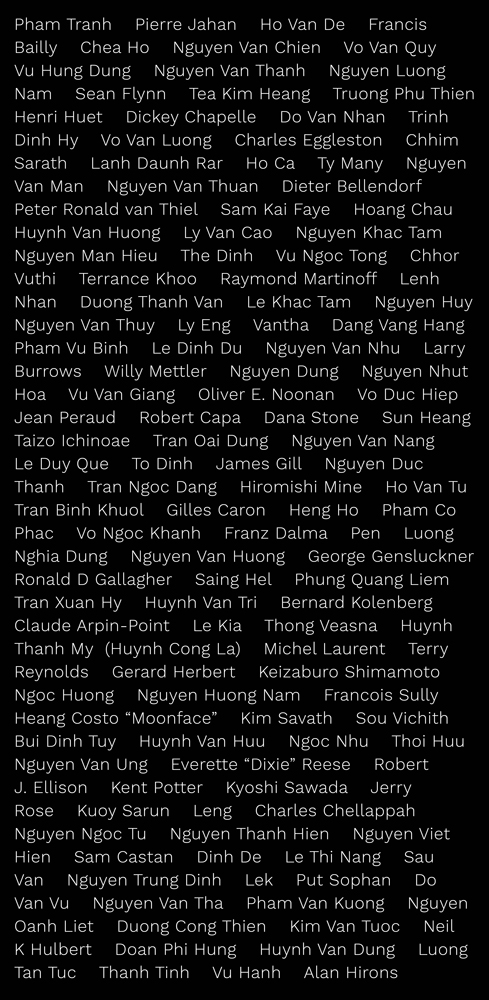

Between November 24, 1945, and April 30, 1975, 135 combat photographers died in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. They were all loved; they were all unlucky. None lived to grow old.

It is for their photographs, not their dying, that the world remembers them.

Luck favours the brave

A wartime survivor speaks out for the first time about his role as a Cambodian war photographer and his escape from the killing fields

Mao Run is possibly the only photojournalist remaining in Cambodia to have survived the Indochina wars and has lived through six Cambodian regimes. A quiet, stocky man with thinning hair, he tells his story to the sound of gentle wind chimes in the otherwise empty restaurant.

Mao Run was named Chey Sarun when he was born on June 5, 1945, and educated in French and Khmer. At the age of 21 he went to work delivering three state-controlled magazines: Kambuja, Le Sangkum and Phseng Phseng. He had been passionate about photography since childhood, so when his brother bought him his first camera he taught himself photography. By 1971, he was working as a photographer for the state-sponsored Interest Khmer newspaper and United Press International (UPI).

When he received his foreign and national press accreditation he immediately joined the Cambodian army in the frontline.

“At UPI we competed with AP. We sent out 30 stories a day,” Run says. His favourite photo opportunities were when soldiers on the battlefield would break for lunch and he would walk freely between the enemy lines to photograph the government soldiers . . . or when the Khmer Republic army flushed Khmer Rouge soldiers out of a bunker and he was able to capture their frightened expressions.

He says he enjoyed his life as a photojournalist because he got to meet so many powerful people. “Once during a meeting between General Lon Nol and Sisowath Sirimatak, the two hugged and my flash didn’t work. I asked them to hug again so I could take the photo. I dared to ask these two powerful leaders to do something for me, and they did!”

Five days before the Khmer Rouge took Phnom Penh he managed to get to meet a number of American diplomats at their embassy. “I went to the ambassador’s [John Gunther Dean] final press conference where he delivered the now famous line of: ‘I have no further comments for you all. I have to go now and would like to say goodbye’.”

Run refused to be evacuated from Phnom Penh and worked until the Khmer Rouge marched into the city. He shot seven rolls of film, which included photographs of government soldiers taking off their uniforms and throwing down their guns near the Japanese Bridge. That afternoon he sent his last news report to UPI from Phnom Penh to Saigon: “SOS. Today it is finished for Phnom Penh and the Lon Nol regime. Now the Khmer Rouge are occupying Phnom Penh and the people are leaving. Please help me.” If UPI responded, Run was not there to receive it.

He left the city four days later with his wife and four children, the youngest of which was 13 days old. The 100km trek to Kampong Thom took Run and his family a month because of illness, frequent stops to gather food and through congestion on the road where events foreshadowed the hardships and lucky breaks to come.

Goodbye: US ambassador Dean, above, with Cambodian troops. Lon Nol before his departure from Cambodia. Mao Run found only two rolls of film when he returned to Phnom Penh

Luck came in the form of a Khmer Rouge soldier who told him that if he wanted to live, he should pretend he was a farmer. Grief struck when his four-year-old son died from a lack of medication and Run came down with malaria. Fortunately his wife’s grandparents picked them up in an ox cart 30km from their destination. “Otherwise I would not have made it,” he says.

His journalistic background prepared Run for the tough and dangerous years ahead under the Khmer Rouge. “I knew from talking to their prisoners what life was like in the Khmer Rouge-controlled areas,” Run says. His wife’s grandfather also warned him how to behave. “After one day the Angkar will win. For sure. You must close your mouth and your ears if you want to survive.” Run changed his name to the one he uses now. “I chose Mao Run,” he says, “because it sounds like a farmer’s name.”

While in Kampong Thom he worked on the First January dam project for four months, barefoot on sharp stone chips. It was his hard work that prevented him from being sent to the killing fields.

“My name was on the list to go, but my district representative recognised me from my work on the First of January dam. He knew I was a hard worker, so he crossed my name off the list and told me to go home, but not by the main road.” In April 1979 he made a cart and made the journey back to Phnom Penh. His personal cost was high: “I lost another child to tetanus and 20 family members, including two brothers and an uncle.”

Run’s last assignment as a photojournalist was in 1998 in Preah Vihar, where he was sent to film the surrender of the last remnants of the Khmer Rouge. The helicopter he was on crashed, but he miraculously escaped unhurt apart from some cuts and bruises. Ever the professional, though, he “took a picture before the crash and after it”.

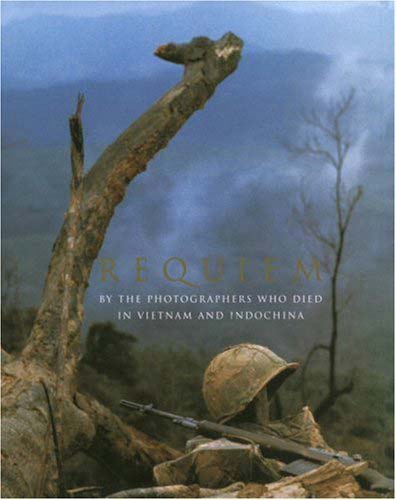

Requiem: By the Photographers Who Died in Vietnam and Indochina

Between the height of the French Indochina War in the fifties and the fall of Phnom Penh and Saigon in 1975, 135 photographers from all sides of the conflict were recorded as missing or having been killed. Edited by German photographer Horst Faas, Requiem is the ultimate homage to those men and women, with the book in many cases featuring the last photographs they ever took. A tribute by the Globe to the late Faas shortly after his death in 2012 can be found here.