Early this year, the Vietnamese central bank had quite a serious quarrel with Moody’s, one of the world’s big-three rating agencies. Moody’s estimated on February 18 that non-performing loans (NPLs) in the country’s banking system total at least 15% of its total assets, more than three times the central bank’s official ratio of 4.7%.

“Capital remains inadequate to absorb the extent of potential losses stemming from pervasive weaknesses in asset quality,” said Gene Fang, Moody’s vice-president. At the same time, the agency kept its “negative outlook” on Vietnam’s banking system.

The central bank, or State Bank of Vietnam (SBV), disputed the assessment almost immediately, saying that if “carefully calculated”, the country’s bad debt ratio was about 10%. This did not help convince wary investors that bad debts were under control.

“Reality shows who is more trustworthy. The central bank has always said the NPLs were manageable and then [following Moody’s statement] they suddenly changed the number to 10%,” said Phan Minh Ngoc, a Singapore-based economist at Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation. “It must have been a prolonged problem but the central bank does not want to recognise it.”

Moody’s estimates the amount of total bad debt at $41 billion while the central bank sees it at $25 billion, if one calculates the amount using their official ratio. In either calculation, the figure is considered as one of the highest in Southeast Asia, and just too high for the banking system to function properly, according to observers.

Since the financial crisis, “the ratio of NPLs has in fact remained the same in Vietnamese banks”, Tran Dinh Thien, chairman of the Vietnam Institute of Economics, stated in April. “This does not only destabilise the banking system but also hinders the capital flow to dying business sectors.”

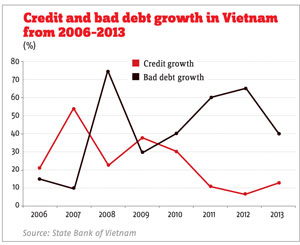

Vietnam’s bad debt trouble stems from its investment-led economic development model. The non-performing loans piled up during the country’s 2004 to 2007 economic boom as banks were eager to lend relentlessly, particularly to state-owned enterprises, which account for 60% of the problematic debt sum. Annual credit growth peaked at a staggering 54% in 2007. By contrast, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) views growth rates in the range of 10% to 15% as sustainable.

When property and stock market bubbles burst in 2008, lending rates climbed up to 25%, challenging many borrowers to serve their debt. The central bank tried to tackle the problem with tighter regulations and forced banks with a weak financial base to merge with stronger ones. So far, eight institutes have been “restructured” or merged with others.

Last year, the central bank established a bad bank, the Vietnam Asset Management Company (VAMC), as a major tool to fight the debt mess. The mission is to clean up the finance sector by issuing “special bonds” in exchange for non-performing loans. However, the result has been disappointing.

Up until now, Vietnam’s bad bank has bought bad debt worth about 50 trillion dong ($2.3 billion), barely a tenth of the system’s NPLs. In the first quarter this year, stated goals were missed even more dramatically as the institute issued bonds worth about $180 million, just 3.9% of the targeted sum for the full year.

While it is obvious that Vietnam should deal with NPLs as soon as possible, there are not many solutions on the table, said Nguyen Minh Phong, an economist at the Institute of Socio-economic Development Research in Hanoi.

Given the VAMC’s limited equity of about $23 million, doubts are widespread that the institute can bear the burden of the country’s NPLs, which amount to more than $20 billion, or 10% of Vietnam’s GDP, according to conservative estimates.

Apart from that, Vietnam has failed to develop sophisticated financial institutions, such as a derivatives market, to help handling non-performing debt with the assistance of the bad bank.

“The prospect of reducing NPLs in the banking system as fast as expected is bleak,” Nguyen said. However, the central bank aims to “solve the fundamental problems of bad debts” by 2015, it said last year.

What’s more, there have been no significant changes to debt classifications and the relevant legal framework, leaving the banking system on a fragile footing.

“The target itself is not important, because the central bank can force banks to sell NPLs to the VAMC,” Sumitomo Mitsui’s Phan said. “The question is how the central bank is going to deal with all the debt. It’s just like going to war without proper weapons.”

The bad bank holds the debt for five years, hoping that banks will be strong enough by then to deal with the issue themselves. “But what if in five years things are not getting better?” Phan questioned.

In the meantime, the bad debt problem has taken a heavy toll on Vietnam’s economy. The high debt level forced banks to set aside huge capital amounts instead of lending to private businesses. Moreover, as banks need high margins to shield themselves against debt defaults, it is hard to see a significant reduction in lending rates even as the central bank eased its monetary policy to foster economic growth.

Current lending rates in Vietnam range from 13% to 16% – among the highest in Asia. Credit growth was negative for the first two months of 2014 before recovering to positive territory thereafter.

The number of bankruptcies climbed 12% to 60,000 last year. Since 2006, half of the 600,000 registered Vietnamese companies have ceased doing business.

The bad debt problem is the “bottleneck” for Vietnam’s economic recovery and long-term growth prospects, Bert Hofman, chief economist East Asia-Pacific at the World Bank, told a conference in early April. “Vietnamese authorities should not tolerate any move to hide NPLs. They must show their determination to deal with it,” he added.

All in all, with the central bank struggling just to measure the scope of Vietnam’s debt mountain, it might be difficult to regain investors’ confidence.