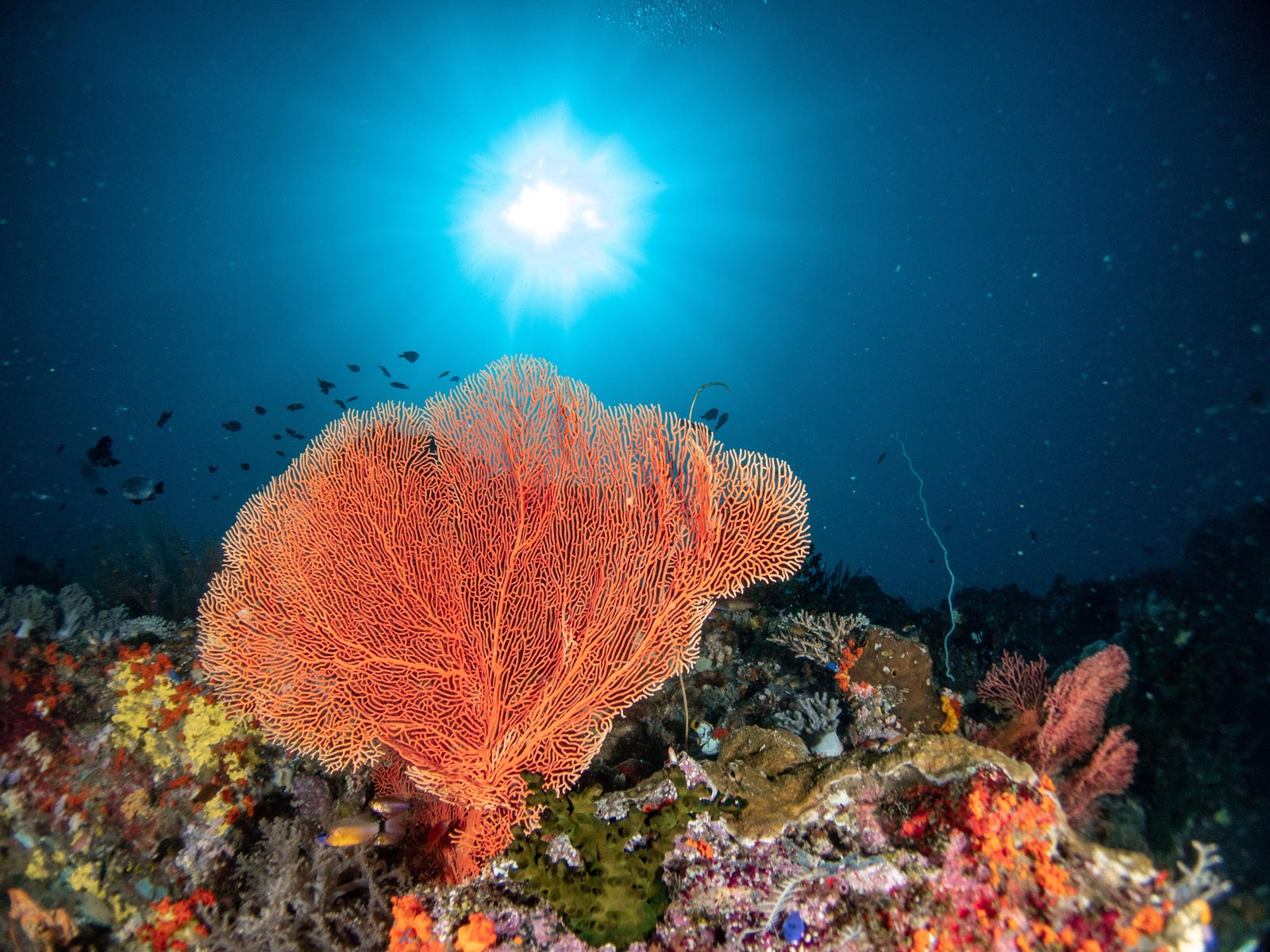

Under the waves, the climate crisis is changing the nature of the oceans. Coral reefs, built on a foundation of hard corals whose calcium carbonate skeleton hold up all the life and colour that we see, are in peril. These hard corals are already being impacted by climate change, with bleaching and ocean acidification reducing them, and the ecosystems they support, to rubble.

But a growing network of scientists and divers believe there is hope. They have seen coral colonies adapt their behaviour to survive bleaching events, or even resist it all together.

Dr Rodney Salm is one such coral optimist, and his research into coral resilience around the world, including observations in Indonesia, is bringing hope to the region. Dr Salm is the senior advisor emeritus for The Nature Conservancy’s Pacific Division Marine Program, and has been focused on coral reef conservation for 50 years.

He believes that we are underestimating the strength of coral to resist the effects of climate change.

“We need to believe that some corals do survive and can survive, and we need to focus on those survivors. Not just as individual corals, but as coral communities and coral reefs. It is those survivors that are the hope for us in the future,” he says on a recent visit to Bali, Indonesia.

Dr Salm’s passion for coral reefs takes him across Indonesia each year, and in February he spent time working with the Coral Triangle Center (CTC), a regional marine conservation organisation based in Bali, sharing his research with local conservationists and marine resource managers.

Dr Salm and CTC want to build up networks that utilise citizen science to identify ecologically resilient coral reefs. These networks would bring together volunteers to support marine conservation projects in identifying key ecosystems, and managing reefs for climate change resilience.

We will see reefs formed by the more resistant corals. We will still have coral reefs, just different reefs

Dr Rodney Salm

This resilience is fundamental to reefs surviving the challenges climate change is creating, in particular mass bleaching events. Coral bleaching occurs when coral polyps become stressed, and the photosynthetic algae with which they live in symbiosis, called zooxanthellae, are expelled.

Zooxanthellae give coral its colour, as well as key nutrients, and without them coral polyps die. If the cause of stress diminishes, the coral can take in the zooxanthellae again and heal. But with rising water temperatures the leading cause of bleaching, many warming events are now so extreme or so sustained that the coral cannot recover.

But Dr Salm says not all coral is affected equally by bleaching. Some are naturally better able to adapt and recover, and supporting coral health before bleaching events means they are more resistant to the impacts of warming seas.

“I do think that we will see the loss of coral reefs in some areas. But I think what we will also see is the change in the communities of coral reefs in other areas, and we will see the expansion in the range of corals, and coral reef formation in yet other areas,” says Dr Salm.

He has seen these changes firsthand, and believes that coral reef conservation plans must incorporate climate change resilience factors. Working with natural resilience, and protecting and supporting survivors of bleaching events could enable faster and greater recovery of reef ecosystems.

Dr Salm says that the resilience of different coral species will mean changes in reefs as the impacts of climate change worsen. “We will see reefs formed by the more resistant corals. We will still have coral reefs, just different reefs.”

Some coral, because of a combination of genetic and environmental factors, can resist bleaching altogether, while others are able to use their environment to reduce the impact. Shade from land or naturally occurring sediment in the water can protect coral from light stress as the water warms, while some areas are protected by the mixing of cold water from the deep, drawn up by currents to blend with the warmer surface water.

Recently, some corals have even been found to change their behaviour to survive bleaching events.

“We are learning so much on coral resilience. There are differences that people are beginning to learn, that corals can control their zooxanthellae, and how they can populate their tissue with ones that are more heat resilient, and how they can move them around [to help them survive],” says Dr Salm.

After a worldwide mass bleaching event in 1998 – one of the worst recorded in which one sixth of the world’s coral died, acting as an early warning on the impact of warming seas – Dr Salm saw how coral reefs across the world were affected, and how they recovered.

Following more recent bleaching events, he saw some of the same coral colonies impacted again. Only this time they responded differently, with the sides of the coral colonies bleaching first, and the top sections showing less signs of stress, or even remaining unaffected.

Dr Salm says this is the result of the coral moving their more heat-resistant zooxanthellae to the top of their structure, where the combination of heat and light stress would normally cause more extreme bleaching. Dr Salm believes this was an adaptive response, so as to lessen the impact of bleaching on the coral colony’s overall health, and enable them to recover faster.

“If corals can do that, it means they are now responding differently to how they did before. I think it is a great cause of hope,” he says.

Hope is the key takeaway here from these findings, says Marthen Welly, CTC’s marine conservation advisor.

“Coral resilience is giving hope to us. Hope for nature in facing climate change issues, and for marine conservation programmes and actions to support the ecological and economic functions of coral reefs.”

Welly has been supporting marine protected area (MPA) management in Indonesia for decades, and is also optimistic for the future of Indonesia’s marine life.

“Coral reefs can be adaptive. We have seen their resilience in facing climate change, as well as other anthropogenic factors.” He sees the health of coral reef ecosystems within MPAs as an indicator for management effectiveness, and believes MPAs can be designed to protect reefs so they can build up their own natural resilience.

Before the conservation area was established I saw a lot of damaged coral. [But now] the coral is healthier because it is protected

Mindu Sondag, an artisanal fisherman

But protecting these reefs is not without its challenges. Indonesia may be the country with the largest area of coral reefs in the world, but it is also dealing with extensive marine pollution, overfishing, destructive fishing, and coastal development. While action to fight the climate crisis must happen at the global level, managing damaging fishing and tourism practices is vital to giving the reefs in Indonesia a chance.

Out in the remote islands of Maluku, the eastern Indonesian province where both Dr Salm and Welly have spent many hours above and below water, surveying the reefs and talking to communities, local fishing families are experiencing the impacts of climate change. Welly and his team have been working with the local government and communities in the Banda Islands to build up a network of MPAs, which aims to support coral resilience, as well as protect marine life and encourage sustainable livelihoods.

Mindu Sondag is an artisanal fisherman who lives on Ay Island in the Ay and Rhun Islands MPA, one of three currently in the network. There is little understanding of the climate crisis here, but like many in his coastal community, Sondag knows what is at stake. He believes the MPA around his island is already supporting the health of reefs, an important factor for their resilience to future threats from bleaching.

“Before the conservation area was established I saw a lot of damaged coral. [But now] the coral is healthier because it is protected,” Sondag explains.

Spending their lives on these coastlines means local residents are seeing the changes to their reefs firsthand, and are afraid for the future of their island. As his community primarily depends on subsistence fishing, Sondag describes how their future relies on protecting these reefs.

“If the coral is healthy, we will see a lot of fish, and they will have a place to spawn,” Sondag says. But a loss in fish stocks would be devastating, and have wider impacts on the preservation of cultures, as well as the national economy.

Despite these hurdles, Dr Salm says Indonesia is in a good position to support the resilience of its coral reefs. Indonesia lies at the heart of the Coral Triangle, widely regarded as the epicentre of marine biodiversity.

Natural conditions like the Indonesian Throughflow, an ocean current conveying warmer water from the Pacific through to the Indian Ocean, bring eggs, larvae and new life through the region. Indonesian marine and coastal ecosystems are a melting pot for marine biodiversity, and the reefs here sustain life that supports healthy oceans worldwide.

This biodiversity is crucial to maintaining reef structures and building up resilience. Dr Salm says that more diverse reef systems will have a better chance of survival, and that conservationists, governments, and marine protected area managers must focus on protecting and supporting diversity, and prioritise areas that are adaptive and resilient.

Dr Salm says he is still energised by the life in Indonesia’s reefs.

“No other place in the world could sustain the reefs in Indonesia, because of all these good features you have here. So for me, Indonesia is a hope spot for coral reefs, I really believe that all the ingredients are here to help these reefs survive.”