Editors Note: Mental health issues among Malaysia’s population continue to surface. According to Hannah Yeoh, Deputy Minister of Women, Family and Community Development, last year the Social Welfare Department saw 1,929 people come in for psychological and counselling services, a 300% increase from the previous year. While political and economic commitment to the issue remains patchy, awareness around mental health issues is slowly growing.

In December 2019, the Malaysian Psychiatric Association, the Malaysian Mental Health Association and Pfizer Malaysia Sdn Bhd launched the country’s first ever mental health handbook to help people recognise symptoms. Health Minister Datuk Seri Dr Dzulkefly Ahmad said at the book’s launch that “valid knowledge for the community is one of the most important steps to promote greater understanding of mental health issues”.

On her good days, Vishalatchi Arunagiri went for flower arrangement classes, wrote, and gave speeches and media interviews as a mental health advocate. On her bad days, the 26-year-old could do none of that. Severe anxiety and a diagnosis of schizo-affective disorder crippled Vishalatchi, leaving her unable to feed, clean or take care of herself. Delusions filled her head. So did the voices – which attacked her mum and siblings while pushing her to kill herself.

As Vishalatchi teetered on the tightrope between productivity and paralysis, she was supported by her 61-year-old single mother, Mala Davi N Thanjappan.

“Visha is very attached to me. I cannot leave her and go to work for too many hours; she often has anxiety attacks when alone,” said the Montessori education consultant. Mala’s freelance career allows her to provide this care, but the downside is irregular projects and pay.

Approximately one in three Malaysian adults suffers from a mental health condition or is at risk of developing a diagnosable mental illness, according to the country’s last National Health and Morbidity Survey (NHMS), in 2015.

Mental health figures into the vast majority of suicides, with 90% of cases associated with mental health disorders, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO). WHO reports an average of 2,000 suicides a year in Malaysia, or more than five a day.

A WHO study in 2016 found that two disorders alone – anxiety and depression – knock $1 trillion off the global economy each year. Many of those living with these afflictions struggle with productivity at work or can’t hold down a job. This squeezes their earnings, which means less ability to pay for mental health treatment. Thus a vicious cycle is born.

Cheaper treatment can flip the script. It certainly did for Vishalatchi, who gets free care at a public hospital as a holder of an OKU card under the government’s Social Welfare Department – OKU stands for “orang kurang upaya”, which means “disabled person” in Malay. This saves Mala an average $247 that she used to cough up every month for her daughter’s treatment at private facilities since mental health treatment is not covered by most medical insurance in Malaysia.

Even paying patients at public mental healthcare facilities save substantially, according to Bridging Barriers: A Report on Improving Access to Mental Healthcare in Malaysia, published by the Malaysian think tank Penang Institute earlier this year.

Take the treatment charges for depression, for example. The report calculated that the total price for psychiatric consultation, psychotherapy and medication is at most $55 a year in public healthcare sectors. In private hospitals, the amount balloons to $2,016.

In its pre-election manifesto, the newly elected government of Malaysia promised to channel more resources to mental healthcare through government hospitals.

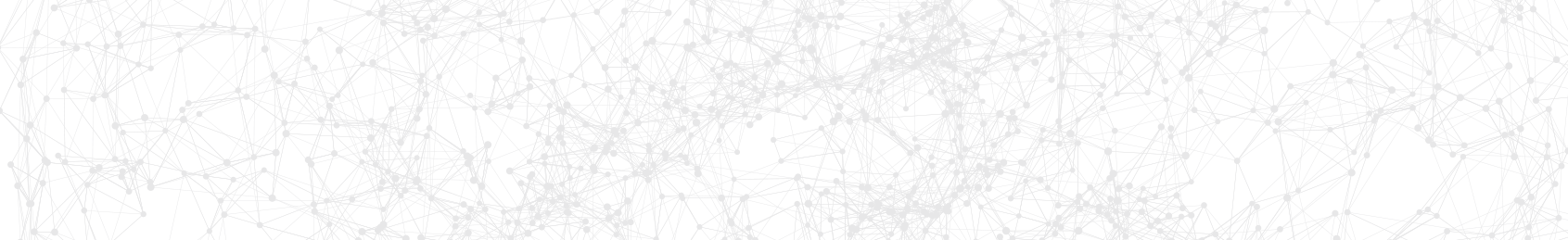

More money would be nice. Since 2012, the Malaysian Ministry of Health (MOH) has spent less than 1.5% of its annual operating budget on mental healthcare.

But money may not be able to fully patch the gaps – not when much of it is caused by a broken system, as laid bare by the dearth of clinical psychologists in public service.

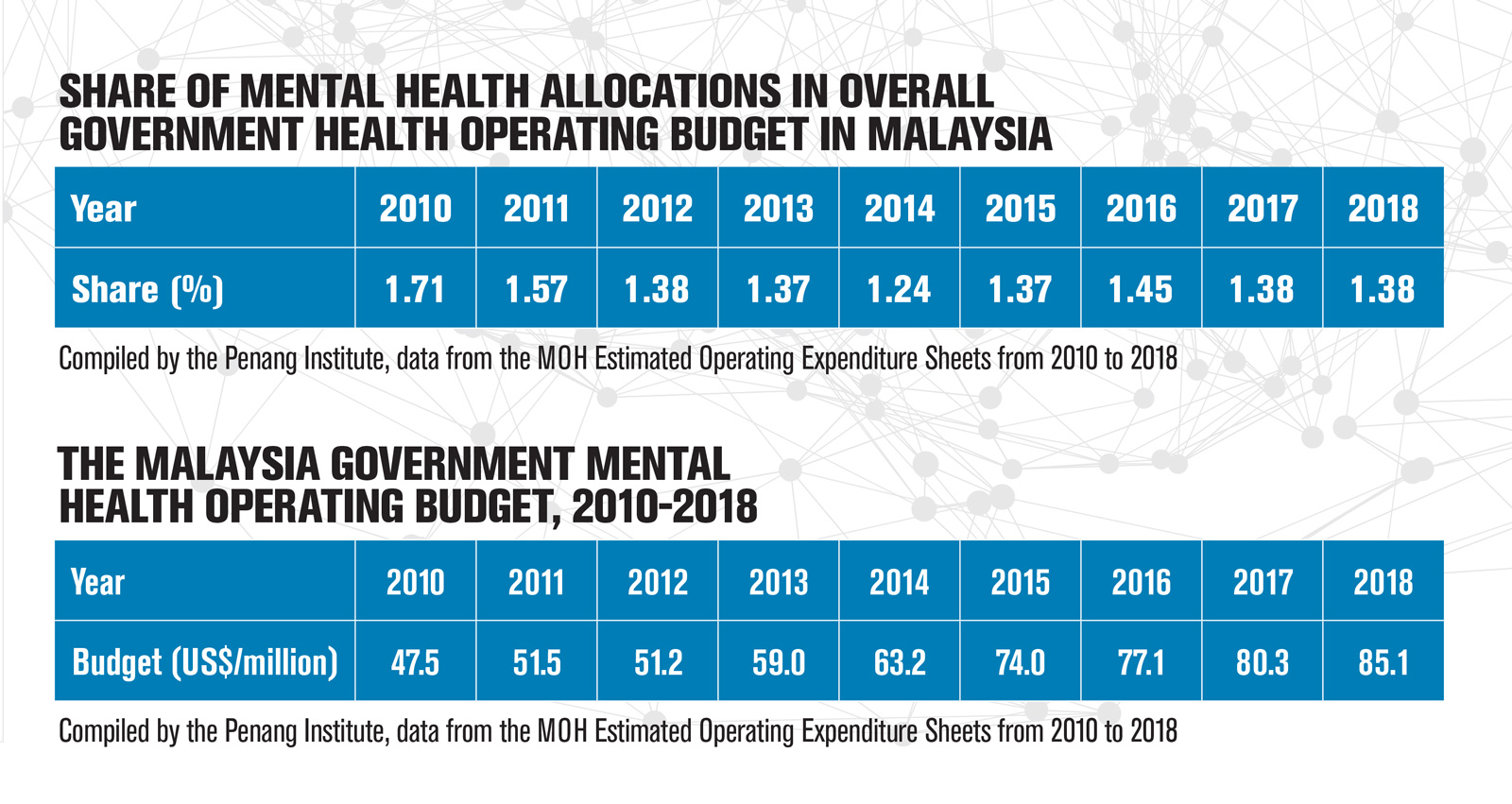

To be fair, the mental healthcare workforce is shorthanded all around. It’s just not a popular career choice in Malaysia. Yet the shortage of clinical psychologists in government-run facilities seems self-inflicted. The MOH has capped its positions for clinical psychologists at 15, even though there are 45 hospitals under the ministry offering psychiatric services throughout the country, according to the Bridging Barriers report.

In other words, more clinical psychologists could not enter the public service even if they wanted to. Here’s why that matters.

Clinical psychologists are instrumental in psychiatric departments. They perform different functions from psychiatrists, but both complement each other in stabilising a patient’s condition. Psychiatrists diagnose mental disorders and offer biomedical treatment, often with medication, but popping pills alone cannot cure underlying issues that lead to a disorder.

Clinical psychologists cannot prescribe medicine, but they are trained to do psychological assessments, crucial for accurate diagnosis of some disorders. They also administer clinical interventions to assist in emotional and mental recovery, as well as long-term behavioural change.

In many cases, clinical psychologists help treatments stick – but there were only 14 clinical psychologists employed in Malaysian government healthcare facilities as of January 2017, compared with 114 psychiatrists. This is actually a step up from 2016, when 12 clinical psychologists were working in these facilities. In contrast, there were 188 counsellors, who deal with less severe emotional distress compared with clinical psychologists within a non-psychiatric setting.

The prevailing sentiment among clinical psychologists is that the government has mixed up its role with that of counsellors.

I’ve personally seen a patient experience more intense symptoms which could have been prevented if the assessment, treatment or intervention had been provided earlier

The recruitment system could be part of the problem. Under the civil service, clinical psychologists are lumped under the same scheme of “psychology officer”, as are counsellors and general psychologists.

But these specialisations have different entry requirements. Clinical psychologists typically need a master’s degree and rigorous formal training, whereas counsellors and general psychologists are qualified to practice with a bachelor’s degree and no formal training.

Recruitment schemes for Malaysian civil servants are designed by the Public Service Department (PSD). In an email reply to Southeast Asia Globe, the department said it sees “psychology, clinical psychology and counselling [as] inter-connected with each other, and no field is better or superior than the other.”

But the PSD noted its recruitment scheme for psychology officers is based on proposals from the MOH – and that ministry declined Southeast Asia Globe’s request for clarification.

Meanwhile, the shortage of clinical psychologists in public hospitals requires a process of triage. Many public facilities have only one full-time clinical psychologist onboard. Dr Daniel Seal, a clinical psychologist, sees this at a public teaching hospital where he works part-time. “But if you work with people with the most complex problems first, they are also the ones who need the most time to treat, so this makes the waiting list even longer,” said Seal, who also runs a clinic at another private hospital. (His site psychologist.com.my discusses clinical psychology issues in Malaysia.)

Long wait times are not a scourge unique to public hospitals – Mala recalled enduring three- to four-hour queues at private facilities as well. She said wait times are especially excruciating for mental health patients like her daughter, Vishalatchi. Her high anxiety was frequently triggered when sitting in a crowded waiting room filled with strangers who were just as stressed.

Some patients are stuck in longer treatment limbo. Ellisha Othman, a clinical psychologist, recalled the triage process during her training in government hospitals in Malaysia. Her supervisors would sort the case files in piles – higher-risk cases went on top and were treated first, while less-critical ones waited.

“I’ve personally seen a patient experience more intense symptoms which could have been prevented or [had] better treatment outcomes if the assessment, treatment or intervention had been provided earlier,” said Ellisha, who is currently the director of SOLS Health, a Malaysian NGO offering community psychological healthcare.

Because the treatment duration for each case was long, she explained, there was often no time to get to the cases at the bottom of the pile. These patients would have to be referred to mental health NGOs or private hospitals.

NGOs like Ellisha’s, which use a sliding fee schedule, can alleviate the patient load at government facilities. Another example is the Malaysian Mental Health Association (MMHA), which has qualified and trainee clinical psychologists to provide therapy sessions for as low as $5 for underprivileged clients.

But red tape binds them. MMHA’s secretary general, Dr Ang Kim Teng, told Southeast Asia Globe that the volunteer outfit has been struggling to obtain a license to operate its Community Mental Health Centre.

“The Private Healthcare Facilities and Services Act does not allow [non-governmental charitable organisations] to operate healthcare facilities, except for hospices and dialysis centres,” said the retired public health specialist.

She added that the MOH acknowledged the need to amend the regulations. But until today, their license approval remained up in the air.

Another channel that can redirect the patient flow from clogged government hospitals is private facilities. In Malaysia, though, it is difficult for patients to separate legitimate clinical psychologists from hacks. Licensing and registration was not required for private practitioners in the field until the Allied Health Professionals Act was passed in 2016. After two years, the registry is still pending.

Dr Alvin Ng, head of the Department of Psychology at Sunway University in Malaysia, welcomes the mandatory registration because he sees it as reining in malpractice and reinforcing clinical psychologists’ role in the mental healthcare system.

The whole mental healthcare system in Malaysia seems to be behind the times

But enforcement could be complicated, said Ng. The act covers a wide range of allied health professions working in clinical, non-clinical and technical settings. The vice president for the Malaysian Society of Clinical Psychology would have preferred standalone legislation for clinical psychology alone.

Despite its shortcomings, Ng said this legislation represents hope for a more regulated profession, given the tepid government support for a standalone law and the lack of qualified clinical psychologists in the country to draw it up.

Unregulated practice is just one issue in the private sector. The other is the steep price. As long as most medical insurance in Malaysia excludes coverage of mental illnesses, treatment at private healthcare facilities will be inaccessible to the majority. Meanwhile, the queue at government hospitals gets longer.

Lim Su Lin, a research analyst at the Penang Institute and author of the Bridging Barriers report, pointed out that countries with private insurance coverage for mental health treatment like the US tend to have strong support for research into local mental health data. Her research in Malaysia, by contrast, was a bureaucratic maze. Tracking down the latest figures from Malaysian government hospitals required her to snail-mail official letters, register her research and apply for approval. And after she jumped through the hoops, she never did receive those data.

The biggest challenge for researchers, to Lim, is the “dispersed nature” of public mental health data that is not compiled into a single “storehouse”.

On top of that, both Lim and Ng said that scientific research into mental health in Malaysia is not as robust as in other medical specialisations. This impedes understanding of mental disorders.

“The deficiencies of data on mental health explain why private insurance underwriters are so guarded against introducing policies for mental health coverage,” Lim wrote in her report. “Without solid evidence-backed data on mental health conditions in our country, it is hard for them to act [since] they would not be able to perform calculations of mental health risk, let alone gauge potential premium rates for mental health treatment.”

Paltry research and the lack of medical insurance coverage may have written the fates of Vishalatchi and Mala.

For the past seven years, Vishalatchi bounced from one confusing diagnosis to another. Every diagnosis came with a new cocktail of medicines, with one doctor refuting another’s prescriptions. Some stabilised her conditions. Some did not. But all of them had to be paid for with Mala’s irregular earnings.

Vishalatchi believes that stronger research would have improved the field’s understanding of complex cases like hers, and better supported her recovery.

“But the whole mental healthcare system in Malaysia seems to be behind the times,” she said.

And because of that, she is kept behind, too.