“Without the Vietnam war, I wouldn’t be”

He shot some of the most iconic images of the Vietnam War, but Tim Page became just as famous for his ferocious appetite for life. Now 71 years old, the famed photographer says he still hasn’t taken his best picture

Most articles about Tim Page begin with a reference to drugs. Something along the lines of: “He lit up his fifth spliff of the morning…” or, “There was a faint scent of opium lingering outside his room.”

“I can’t avoid the truth, I do smoke a lot and did a lot of drugs and am known for it,” says the 71-year-old as we sit on the sun-pocked patio of a quiet hotel in Kampot, southern Cambodia, watching fishing boats churn their way down a peaceful river.

But, he adds, his reputation as a “wigged-out crazy”, a “stoned-out freak” – descriptions of Page in Michael Herr’s classic Vietnam War book Dispatches – is starting to fuck him off a bit.

“I don’t want to sound like a wanker… but my photos hang in the Tate in London and the Smithsonian in America…”

Tim Page

“What annoys me is that it clouds what I really do well: I can make a reasonably good picture, I can make an iconic picture,” he says, pausing to drain the remnants of his lime juice – nowadays, he limits himself to consuming alcohol only after midday. “I don’t want to sound like a wanker,” he adds, gesticulating the word with curved fingers against his thumb, “but my photos hang in the Tate in London and the Smithsonian in America – they wouldn’t be there unless they were good.”

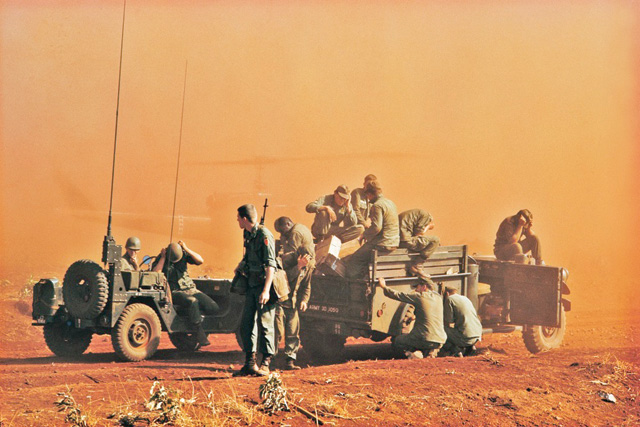

These photos include many he took during the Vietnam War. Page arrived in what was then Saigon in 1965, a 20-year-old Brit a long way from home. Despite being an inexperienced photographer – he had only been making a living from photography for a few months in Laos before being offered a job with the wire service United Press International in Vietnam– it was not long before his images of worn-out US servicemen and Vietcong guerrillas were gracing the pages of Time, Paris Match and other leading publications.

It was also during this conflict that his aforementioned reputation was incubated. He was known for getting closer to the action and into more dangerous situations than most war photographers. As a result, he was injured four times, once or twice almost fatally. The last injury left a piece of shrapnel embedded in his head that could only be removed by also removing tissue the size of a tennis ball from his brain.

“And I’m sick of the Dennis Hopper questions,” says Page, apropos of nothing, suddenly returning to the issue of his reputation two hours into our interview.

He is referring to the fact that his gung-ho nature and extroverted personality led Francis Ford Coppola to use Page as the inspiration for the whacked-out, drug-addled photographer played by Dennis Hopper in Apocalypse Now.

This is the way he speaks – in a permanent ellipsis, non-linear to the extreme, though by no means is his scrambled chatter unenjoyable. Trains of thought regularly take unexpected detours, such as a long monologue about the inhumanity of war that dovetails into a ten-minute analysis of the best place to hang paedophiles in London.

One topic constantly on Page’s mind, however, is photography, especially from the Vietnam War. But this is no mawkish nostalgia – many of his friends and colleagues lost their lives during the conflict, as did those on both sides of the war who he immortalised on film.

For decades, Page has devoted himself to commemorating those who died. In 1991, he established the Indochina Media Memorial Foundation, which sells the prints of photographers who covered the conflict, with the proceeds helping to train young Vietnamese photographers. Six years later he co-published Requiem, a highly acclaimed book that presented the work of 135 correspondents and photographers, from both sides, who died during the war. This collection is now on permanent display on the top floor of Ho Chi Minh City’s War Remnants Museum, as are Page’s own images of the conflict.

In April, he was invited back to Vietnam by the government to help the country commemorate the 40th anniversary of the war’s end. “I was on a Vietnamese TV show, standing there in front of my photographs, and a journalist asked me why I snapped all of the pictures. And it was like a big flood – ‘click, click, click’ – of faces, the friends and people I met from those days who are no longer alive,” he says. “I don’t know why, but I just started balling my eyes out. There was no control. I felt like such a twit-turd.”

During his half a century as a photographer, Page has also covered events from Timor-Leste to Afghanistan, from Cuba to Cambodia. He has spent much time in the latter, in an ongoing attempt to discover what happened to friends and fellow photojournalists Sean Flynn and Dana Stone, who were captured by the Khmer Rouge while on assignment in Cambodia in 1970.

But it is the Vietnam War that both haunts and sustains him. At one point he comments that: “Without the Vietnam War, I wouldn’t be.”

“Every image taken, in a way, was anti-war and captures something that is basically obscene, profane and immoral.”

Tim Page

Dressed in pale cargo shorts, a loosely buttoned shirt and a green-chequered Cambodian scarf, known as a krama, that seems to never leave his neck, Page speaks in a low-pitched drawl, enunciating each word as if it’s his last. His vocabulary, peppered with anachronistic yet meaningful turns of phrase, also imbues certain sentences with an almost philosophical weight.

“The photography of the war changed the course of history like no other time,” he says. “Unlike in other wars, where you had to take the photo, develop it and then send it back home by post, which could take days, the images of Vietnam could go around the world the same day and appear in print the next. Every image taken, in a way, was anti-war and captures something that is basically obscene, profane and immoral.”

“You were always walking a fine line between understanding the meaning of life and death. It’s like in Apocalypse Now, when someone says the conflict is like sailing on the edge of a razor blade.”

Page’s reminiscences stand in stark contrast to the way some older men talk about their ‘glory days’. Except for the odd occasions when young women in skimpy bikinis walk past our poolside table, prompting Page to joke about his virility during the war, he says he doesn’t miss those youthful days of action and insanity. The one thing he wishes he did more of, however, is take pictures. “I think of all the images I didn’t take,” he says. “It’s not regret, I can just see now the ways I could have improved.”

Page now lives in relative comfort in a 17-room house in rural Queensland, Australia, with his wife. But he says he has a modest pension and money stash. “I guess my archive is my pension, but I have to keep on finding places to publish them,” he adds.

This sets Page off on another angry monologue, this time about the life of a modern freelance photographer. “Getting images into meaningful publications is much harder than it used to be. Every motherfucker has a camera or iPhone,” he starts, regularly dipping his head towards my dictaphone to fire off an expletive. “And day rates are fucked. Millions of people want to be photographers. I see all these eager beavers sat in classrooms… and even if you did shoot the most incredible image, who’s going to publish them? There are no more magazines that sit on coffee tables, and stuff online is looked at and then fucking deleted.”

Suddenly, though not uncharacteristically, his irritation recedes as he admits that he is never too short of work. “I regularly get calls from very weird publications to do some weird stuff – motorcycle races or wacko weddings. Maybe it has something to do with being known as a character, my reputation,” he says. “I worked with Hunter S. Thompson on completely gonzo things, or whatever you call it. Over the past few days I’ve had four or five weird shit – commissions – come by email.”

Yet weird shit seems to sit well with Page; he does not consider himself too important to accept such jobs. “I suppose the thing about being freelance is that you get to do interesting things, whether it’s a rock concert or portrait shoot, even a wedding. It tests your capabilities to put your lick on the story, your own spin or personality, and flex that muscle in your own little selfish way, your own artistic way,” he says.

With that, he excuses himself from the interview. As he makes his way to the bar, it is hard not to notice that he doesn’t walk as much as hobble. While he says this is due to a motorcycle accident as an adolescent that left him with a five-inch bolt in his hip, which did happen, there is an inescapable fact: Tim Page is getting old.

Page getting old is like a Ferrari under the process of oxidation, an Olympic sprinter with arthritis. “If I had the energy and resources I’d go and do a lot of things,” he says. “But physically I can’t do it, and that fucks me off too. I haven’t got that much time left. I shouldn’t be smoking and drinking so much. Why don’t I obey my own body?” he asks but never answers.

If, as he says, he hasn’t got much time left, Page is certainly not going quietly. In many ways, he is a throwback, a product of a time when society was less sterile, a man who came to maturity during one of the most savage and senseless wars of the past century. And he refuses to change. It would be difficult to imagine Page following the latest health-food trends or sucking on something that wasn’t carcinogenic. It would not be difficult, however, to imagine him smoking, drinking and, more importantly, being a participant in life rather than just an observer, right until the very end.

“I still haven’t shot my best picture yet. You can get close to perfection, as close to the 100% feeling as you can, but somehow you know it can still be better. You see someone else’s photos of the same event, and you think: ‘Why didn’t I catch that thing?’” he says, crushing out a cigarette and cracking a wide smile. “But it’s okay, you did your own thing.”