The ‘Girl Power’ revolution came late to Myanmar, the audience wasn’t ready when it arrived and by the time the country was prepared to embrace it, it was over.

It began when a Burmese man and an Australian woman crossed paths in Yangon eight years ago and quickly recognised a shared musical passion: Moe Kyaw was a music producer with a few local successes under his belt; Nicole May a dance teacher flitting about the city and doing volunteer work. It wasn’t long before they were business partners.

Fifteen years had passed since a casting call in central London first brought together the Spice Girls, giving birth to the original ‘Girl Power’ crusade, which turned out to be the biggest musical juggernaut of that decade, inspiring a legion of copycat acts across the world. Now it was Myanmar’s turn.

Nearly 200 women showed up for the audition staged by May and Kyaw in early 2010; by day’s end, there were five remaining. That week, Ah Moon, Htike Htike, Cha Cha, Wai Hnin and Kimi were taken to a makeshift studio in Yangon to begin a gruelling regimen of singing and dance training.

The Tiger Girls debuted three months later in Mandalay during the country’s Thingyan festival, the annual bacchanal of teenage drinking and public water fights that heralds the Myanmar New Year. Their provocative dress prompted a hostile reception, though. According to a contemporary account by British journalist Rosalind Russell, the women were pelted with plastic water bottles and footwear.

Yet in the three years that followed, they became an international sensation – if not one that ever found a sizeable following in their own country. As Myanmar began its slow transition away from decades of military rule, the Tiger Girls became, in the eyes of foreign media, an exemplar of the profound political changes taking place. They spoke publicly about their commitment to challenging the entrenched discrimination facing Myanmar women and their absurd battles with geriatric censorship authorities, such as when they were banned from performing in coloured wigs. After several performances in the region and further abroad, they were offered a recording deal with the Power House music label in Los Angeles.

But just as they seemed to be breaking through to a domestic audience, it fell apart. Moe Kyaw and May had parted early on in the venture, after the producer was frustrated in his efforts to tone down the act’s flirtatious image. He reserved his rights to the group’s name, though, forcing a reluctant rebrand as the Me N Ma Girls. Then, soon after releasing their second album, Wai Hnin left the group, ostensibly because of pressure to take care of her elderly family. Six months later, Cha Cha and Htike Htike also went their own way, after learning that their record deal left Power House with rights to their solo work. The remaining two members persevered for a month, before Kimi resolved to focus on her own solo career.

As difficult as it was at the time, it was ultimately fortuitous for the group’s breakout star and youngest member. “I was the only one who was left in the group!” Ah Moon told Southeast Asia Globe. “People have this myth that Ah Moon left the group and became popular, when the truth is everyone left to do their own things, and I was left sitting here. Then management asked what are you going to do, and I said: ‘I’m gonna keep singing!’”

Ah Moon spoke with Southeast Asia Globe from a rooftop wine bar in Yangon’s Myaynigone neighbourhood. Born in the Kachin capital of Myitkyina, in Myanmar’s far north, she began her music career at the age of four while performing in church halls and inked a deal with Myanmar Beer as a touring performer straight after finishing high school.

Now 26, she had just returned from a whirlwind tour of Japan, performing for the Myanmar migrant community there and filming two music videos from her forthcoming album. Now undoubtedly a national phenomenon, Ah Moon has attained 2.5 million Facebook fans in the three years since her solo career began.

It’s getting easier now… Back in 2014 I was called slut, bitch, told to get out of the country… But those words are not from the crowd; those words are only from the people that see the pictures [of me] on social media.

After the split, the other four Tiger Girls pursued their own solo careers with varying degrees of vigour. Then, in 2015, a year after the group’s final official single, the foursome announced their return as a group, reinvented once again to become the MyaNmar Girls.

Both Ah Moon and Cha Cha, who spoke on behalf of the group, said there was no acrimony on either side over the split and the formation of a new group that excluded one of its founding members. For Cha Cha, the group wanted to build their careers on their own merits, while Ah Moon continued with her overseas management.

“When we decided to leave the group, we were all prepared to leave all the things of the old group, the support, the international interest and especially the budget,” Cha Cha said. “So as a result, we had to face all these challenges without the support which we had [come to expect].”

A year after they got back together, Wai Hnin suddenly stopped appearing on the group’s promotional material. Ah Moon suggested she had been kicked out, something Cha Cha denied. She did admit there had been disagreements but said that Wai Hnin had decided to stop pursuing a career in music and now works at a private company, regularly catching up with the other three.

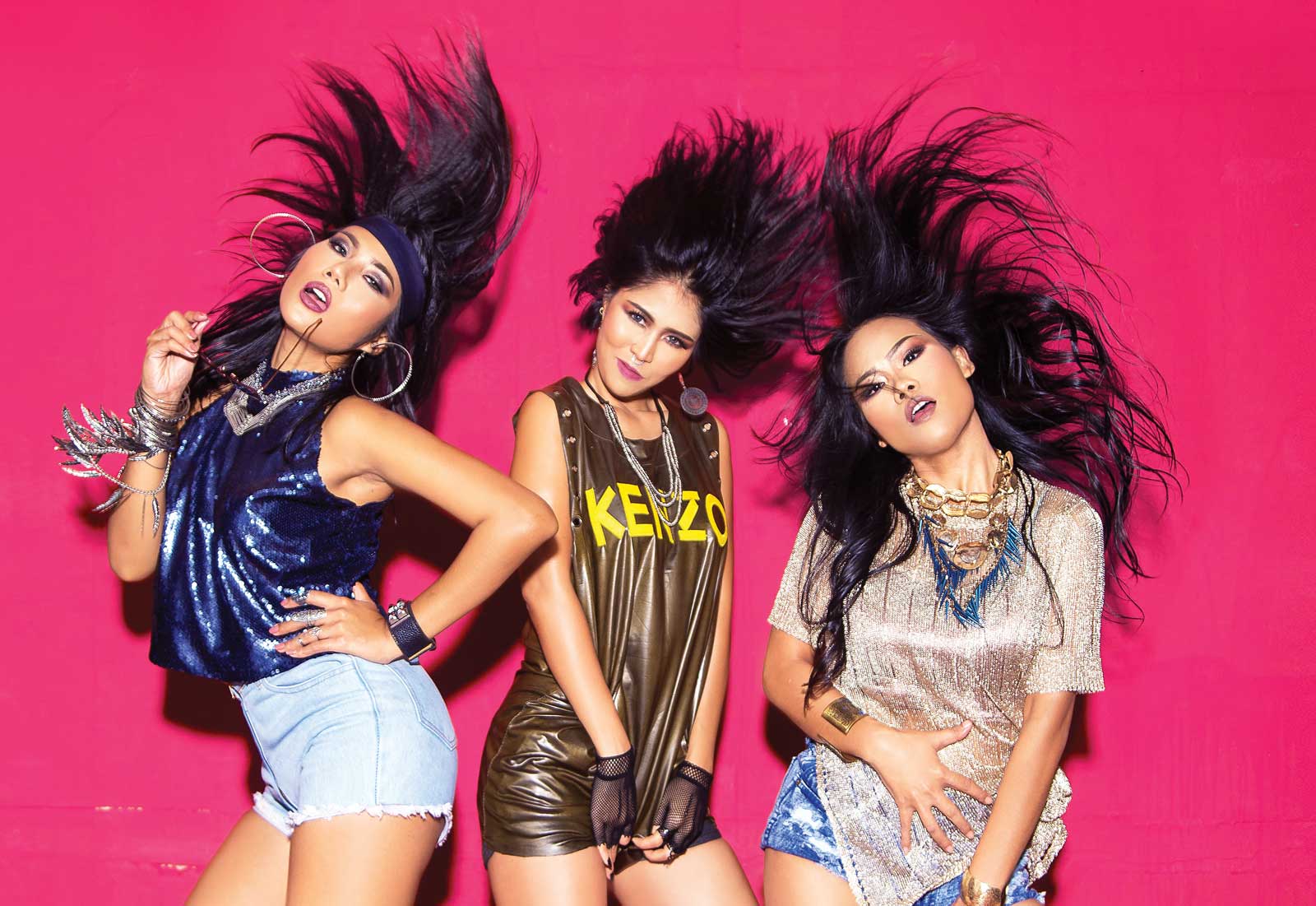

While the remaining trio have become national celebrities, appearing regularly on magazine covers and at high-society events, it has been challenging to work in a music market dominated by a small number of acts with big financial backing. The group’s debut last year, the up-tempo and raunchy Shake It!, was entirely self-funded without the resources for a big promotional campaign on billboards and in print media.

But unlike when their careers began, the audience is there. A market for the assertive, come-hither style of pop music on which the Tiger Girls built their brand now exists in Myanmar. The credit is all theirs.

“It’s getting easier now,” Ah Moon said. “Back in 2014 I was called slut, bitch, told to get out of the country… But those words are not from the crowd; those words are only from the people that see the pictures [of me] on social media. I had the love of all my fans who saw me face-to-face. They loved my performances; they supported me. I had the courage and the energy to overcome that… and that moment of being criticised is kind of over.”

Yet, in other respects, breaking out as an artist has become harder. The new government, led by Aung San Suu Kyi, has long been accused of a puritanical streak that rivals that of its predecessor and has made regular noises about the need to tone down the excesses of the Thingyan holiday. One of the MyaNmar Girls’ first public performances in 2015 was a headline slot in front of a rapturous Thingyan audience in Mandalay, the same time and place where five years earlier they’d been heckled mercilessly. This year, a ban on commercial stages at the festival meant the MyaNmar Girls couldn’t perform at all.