Seng Vannak looks up from his desk at Phnom Penh City Hall to see numerous sepia photographs of the capital pieced together on the wall across from him. They are the first shots ever taken from above the city for architectural purposes and reveal some of the urban planning and development that had been put in place in the 1950s.

Vannak, the exciting, young architect tasked with helping orchestrate Phnom Penh’s modern urban sprawl, says these images show the framework of a beautiful, Paris-inspired street grid. They also bear the challenges the municipality was left with after the city centre was conceived under French colonial rule and Cambodian independence was claimed in the 1950s – from a lack of parks to the limited capacity of the city’s streets.

“This city – we didn’t create [it]. We inherited it this way,” says Vannak, the deputy chief of urban management at City Hall, seemingly as a means of explaining away issues that remain unresolved. In this inherited city the Tonle Sap river hugged the east side and districts were linked by a handful of thoroughfares that maintain their prominence today.

According to some of Phnom Penh’s most promising young architects, though, the city’s chequered history of urban management has scarred its present and compromised its future, allowing rampant private development that lacks consistent planning or thought about how Cambodians inhabit their space.

The resulting issues are numerous, they say. Streets throughout the capital are becoming increasingly clogged with traffic, and homes lack functionality due to developers copying blueprints and squeezing buildings onto precious land. Condominiums cut into the skyline, attracting foreign buyers without meeting the needs of locals. Public spaces, from sidewalks to libraries and parks, are limited at best. Nonetheless, the same architects agree that the city has the potential to become a vibrant, community-focused metropolitan hub – if provided with a bit more direction.

“It’s not just [about] the look of the architecture, but what will happen when humans start to take over the space,” 37-year-old Hun Chansan, founding director of Re-Edge Architecture and Design in Phnom Penh’s plush BKK1 neighbourhood, says of architecture’s role in guiding the city’s ongoing development.

This small port town began its evolution from wooden homes to modern city in 1865 when it became the country’s new capital, taking on the land laws of its colonisers in the process. By the 1940s, beautiful, French-inspired architecture began sprouting up throughout the city, earning Phnom Penh its nickname of ‘the pearl of Asia’.

A street grid and urban master plan was formulated, sorting the city into four main districts – Chamkarmon, Daun Penh, Prampi Makara and Tuol Kork – as developers prepared for the city’s expansion and industrialisation.

It was abandoned … Not only abandoned, but also we lost a lot of documents concerning urbanisation, urban management, urban planning. We lost also a lot of competence on urban planning, like how to work with the city

Architect Seng Vannak

The execution of these plans was cut short in 1953 by Cambodia’s independence from France, but a group of Cambodian architects, including the late and much-admired Vann Molyvann, continued to build up the city with ‘New Khmer Architecture’, a distinctly modern style that incorporated nods to established Cambodian structural techniques as well as the country’s tropical climate.

Structures including the city’s Independence Monument and Olympic Stadium were erected by these visionaries, and the country’s rural citizens poured into the capital, doubling its population to about one million by the 1970s.

But civil war and the city’s evacuation by the Khmer Rouge regime in 1975 left Phnom Penh virtually untouched for years.

“It was abandoned,” Vannak says. “Not only abandoned, but also we lost a lot of documents concerning urbanisation, urban management, urban planning. We lost also a lot of competence on urban planning, like how to work with the city.”

Without maintenance, the city’s architecture and infrastructure weathered. Despite the overthrow of the Khmer Rouge in 1979, control over urbanisation was not returned to City Hall until the early 1990s as the country rebuilt its political system with UN assistance. A master plan for urbanisation was not finalised until 2015.

“The most important [factor] for that master plan is how to protect the city centre to keep this urban fabric which is our heritage,” Vannak says, walking over to the images on his wall and outlining the perimeter of the city’s four districts with his finger. City Hall wants the city to continue to grow beyond these boundaries, “but to grow with some history as well”.

Immediate urban management plans include the completion of the city’s 6.8km ‘riverside walkway’, the clearing of sidewalks overtaken by shops and vehicles and the designation of a network of streets as one-way to help traffic flow, he says.

Meanwhile, private development is already booming. By the turn of this year, Phnom Penh was home to an estimated 8,600 condominium units, with 13,000 more due to be completed by the end of the year, according to data collected by real estate services firm CBRE Cambodia. Vannak says that nearly 2.5 million people occupy the capital day-to-day, including those living outside the city centre and those commuting in from nearby provinces.

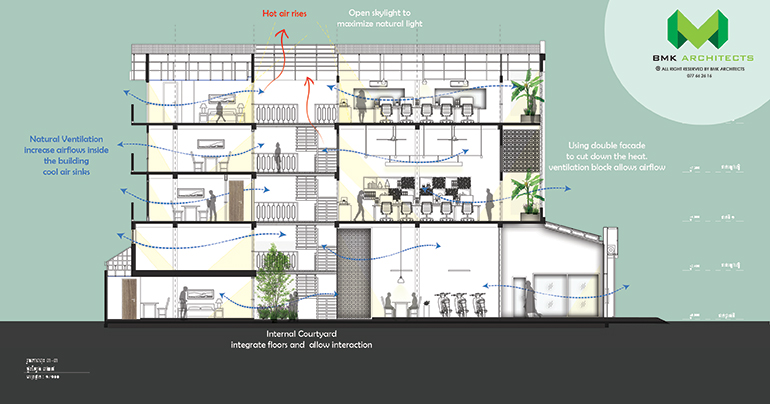

Unfortunately, the development aimed at accommodating such numbers rarely takes into account architectural features such as natural light and airflow, often creating stale homogeneity across residential developments, according to Sok Muygech, the 26-year-old founder of BMK Architects in Phnom Penh.

“They don’t care about the function inside the building, they just know that they want to sell out,” she says. “As a designer, you have the power to control the lifestyle of the people. If you design the kitchen in the front, they’ll have to cook in the front. If you design the living room in the back, they’ll have to stay in the back. So you have to think a lot about how users will experience the designs.”

Hollowing out the middle of Phnom Penh’s long, narrow shophouses from the top floor to the ground has become something of a Muygech calling card, with the architect keen to make space for light and fresh air. A digital blueprint of her redesign for a four-storey shophouse with a pharmacy on the ground floor shows beams of natural light stretching from a ventilated skylight down to a green courtyard at the centre of the ground floor. Each floor receives sunlight from the glass tunnel that runs from top to bottom of the building. Her team’s focus is always “how we can change the lives of the inhabitants”, she says.

As cities grow, you want to look into other types of development, not just private. I think you should look into more education – cultural centres, libraries. All those public service kinds of buildings should be growing as well

n Chansan, founding director of Re-Edge Architecture and Design

Chansan has a more zoomed-out view of the city. In recent years, foreign investors have poured into Phnom Penh, erecting skyscrapers and condominiums that have transformed the city’s previously low-slung skyline. Too much of this, though, and the city becomes imbalanced, he says.

“As cities grow, you want to look into other types of development, not just private. I think you should look into more education – cultural centres, libraries. All those public service kinds of buildings should be growing as well,” he says.

BKK1, the area where his stylish firm sits, is the focus of Chansan’s vision for the city. He sees its future as an interactive walking neighbourhood with historical hubs, community and shopping centres that attract both locals and tourists. Re-Edge is currently developing an open-air mall, which he hopes will draw in community members without making them feel like they’re stuck in the confines of a shopping centre. Airflow, natural light, green space and floor plans that encourage exploration will guide visitors from one floor to the next, inside and out, he says.

“Hopefully that will kickstart the idea of a community street, community mall and then it might… take over slowly,” he says. “But then, like I said, it must involve a bigger scale.”

Chansan says people with prime real estate in BKK1 should move out of their central homes to make room for community developments, and private developers should work towards creating self-sufficient sub-cities where schools, shopping centres, community spaces and government buildings are all available without having to commute into central Phnom Penh.

Just south of the city centre, a sub-city is exactly what developer Kean Kim Leang is working on. A set of 180 condo units inspired by traditional shophouses are set to stand 20 storeys high as starter homes aimed at locals. Beside them is the Factory, a co-working space that will host arts, F&B and startup businesses.

The two projects, which he is developing alongside his American business partner Corbett Hix, are meant to make up a “small city within the city”, according to Leang. Cars and motorbikes will be banned from the streets of the community, instead being consigned to a car park on the tail end of the property to discourage their use. Bicycles for cruising the plot will be available, and the hope is the developments will cultivate a sense of community and collaboration.

But as urban development continues, the biggest challenge will be convincing the city’s population of the benefits change can bring, says Vannak. Pilot programmes to slowly clear up the hectic streets and educate the population on functional city living are likely the only way to create long-term change, he says.

“The local population, they don’t see the potential” of the city, he says. “What we’re trying to do right now is… provide better spaces for the population without real gentrification.” In simple terms, he adds, “keep this vibrant city”.

Developers must be more focused on evolving Phnom Penh for the use of its inhabitants so that citizens are not constantly upheaved by change, Leang says.

“I want to see developers in the future… focusing on what people want or what people need and then spending time on the design. Because, like it or not, they are changing part of the landscape,” he says. “It’s like a canvas: if you draw something, it’s going to stick for the next 30 years.”

This feature was corrected on 5 March 2018. The original mistakenly identified a photo of a Re-Edge development as a BMK Architects remodel.