Editor’s note: Nuon Chea, so-called Brother Number Two and chief ideologist of the Khmer Rouge regime, is dead. Before his death at 93, the former prime minister of Democratic Kampuchea had been unrepentant, convicted of genocide and crimes against humanity by a court he refused to recognise. This article is not about Nuon Chea. It’s about a man who risked his life in the midst of genocide to protect the villagers under his care. As the increasingly paranoid regime turned upon itself, unleashing purge after purge against the people it had called upon to rebuild Cambodia, one local cadre gave shelter to those sentenced to die. Seven years ago, the late journalist and filmmaker Dave Walker tracked down former village chief Van Chhuon and shared his story.

“The dogs always knew when people were being killed,” explains Van Chhuon. “They would howl to each other, from village to village, a very spooky howl, unlike anything I ever heard before. I believe the dogs saw people’s ghosts. In Khmer we say, chakai lou.”

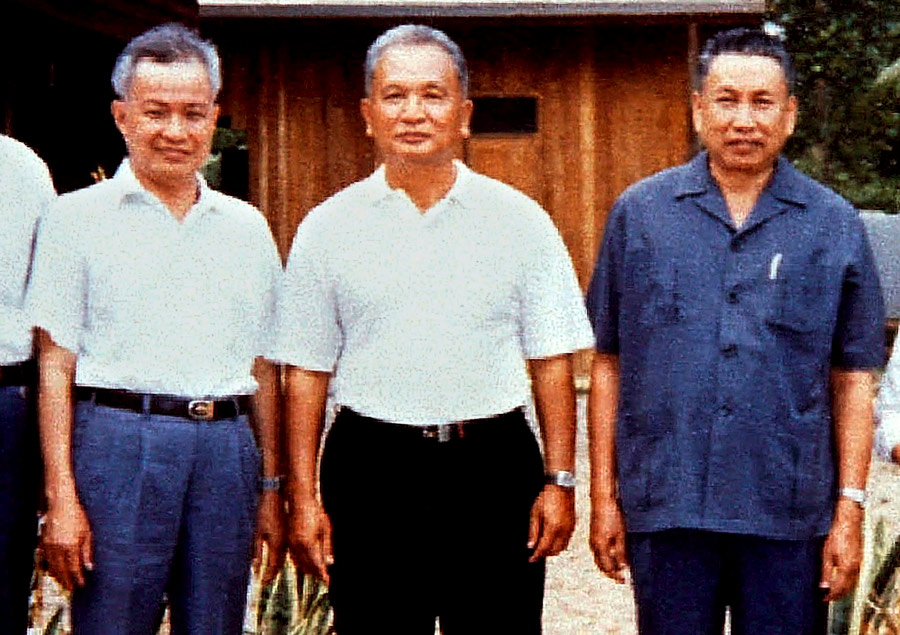

So says Van Chhuon, 64, a former Khmer Rouge village chief, yet the reverence with which he is treated is at odds with the usual perception of the regime. In the village of Kuok Snuol, close to Siem Reap airport, small groups of elders gather to greet him. Their respect for him is genuine, and moving. Some still call him may (boss).

They have never forgotten how Van Chhuon saved this small village of about 100 families during the Pol Pot regime’s bloodiest purges.

In 1970, like many peasants, Van Chhuon worked as a rice farmer and builder. He knew many of the Khmer Rouge guerrillas – local boys, recruited from the surrounding villages. As the war escalated, so did American B-52 bombing missions. Yet the havoc resulted in Van Chhuon meeting his future wife, Yim Hoy, who had fled the shelling in her own village.

“The Khmer Rouge did not allow anyone to possess rice, and hiding food was punishable by death”

Yim Hoy

Fighting drove the young couple from village to village, where they would hide in bomb craters, often having to supplement their diet with frogs, insects and lizards. Several times, Van Chhuon was forced by guerrillas to dig graves, and to carry the dead and wounded.

In 1974, in the village of Dumbrai Goan, Yim Hoy gave birth to a son, Chen Heng, in a makeshift hut. But the following year, the Khmer Rouge took control of the country and began organising the villages into communes, called sangkats.

Sangkat Siem Reap had ten villages, each with a village chief. Van Chhuon was settled into the village of Kuok Snuol, where he took on the perfunctory role of scaring birds away from rice fields, while his wife served food in the communal kitchen.

“The people requested that I work there because I always gave out fair portions,” she explains. “The Khmer Rouge did not allow anyone to possess rice, and hiding food was punishable by death. Sometimes we’d see arrested people being taken to the commune office. From there, they’d go to the old French prison in Siem Reap.”

“I knew if one of my villagers was arrested, they would be tortured into giving information, then more people would be arrested. They might also tell them we were hiding food, and then I would be arrested with my family”

Van Chhuon

In September 1977, the Khmer Rouge regime turned on itself with increasing ferocity. Troops from Takeo province arrived and arrested the existing soldiers, village and commune chiefs, who were thrown into trucks and taken away to be killed. The new administration wanted new leaders, and only from the purest of the base people.

Van Chhuon fitted the bill, after the residents of Kuok Snuol identified him as the poorest man in the village. The Khmer Rouge appointed him village chief and his first job was to bring the former commune chief, Ta Khan, for a meeting at the commune office. “When I saw the soldiers, I knew they were going to kill him. There was nothing I could do,” remembers Van Chhuon.

Obsessed with internal enemies, this aggressive new Khmer Rouge administration ordered village chiefs to report anyone suspected of disloyalty, hiding food or being pro-Vietnamese. Some chiefs reported people out of fear; if they didn’t find enemies, the regime might suspect them. In the neighbouring village of Wat Svay, over 80 people were executed. “Their chief was not a bad man,” says Van Chhuon. “He was just easily led.”

As village chief, Van Chhuon suddenly had the power over life and death thrust into his hands. Defying the Khmer Rouge for two brutal years, Van Chhuon ensured his villagers hid extra rice in the small amount of gruel they were allowed, and stashed any excess food outside their home.

“Khmer Rouge spies would search houses while people were out working,” he says. “I knew if one of my villagers was arrested, they would be tortured into giving information, then more people would be arrested. They might also tell them we were hiding food, and then I would be arrested with my family.”

His wife, Yim Hoy, recalls living “in constant fear”.

“Every time my husband was called to a Khmer Rouge meeting, I never knew if he would come home, especially if they came at night,” she says. “Four times I thought I would never see him again.”

To avoid suspicion, Van Chhuon kept up appearances. “I would tell my villagers that if they stole a potato, I would bury them in the potato field. Or if they stole a banana, they would be buried under the banana tree. I had to be a good actor.”

One villager, Ta Kuol, 65, recalls how Van Chhuon’s diplomacy saved his brother’s life after he had become embroiled in a number of sexual relationships with local women. “My brother knew he would be killed, so he climbed to the top of a palm tree, threatening suicide. We talked him down and went to see Van Chhuon. At a meeting, it was decided that no report would go to the commune office, because [my brother] would have been killed.”

When I saw Van Chhuon, I couldn’t believe it. He assigned a villager to take care of me. Today, I am alive because of Van Chhuon

Nai Kong

Another Kuok Snuol resident, Nam Van, 57, also remembers the liberal hand with which Van Chhuon ruled the village. “My job was to mill rice. Van Chhuon was always kind, and never reported anyone to the authorities. [Contrary to Khmer Rouge policy] marriages were never forced; both parents would agree to it and then the couples would be married at a village meeting.”

When the Khmer Rouge came to arrest a villager, Van Chhuon risked his own life by lying. His usual smokescreen involved telling soldiers the person had already been taken, or that nobody by that name lived there.

When fellow villager Nai Kong, now 58, was arrested for complaining about the regime, he was taken to Siem Reap prison. Showing his many scars from that time, he recalls “there were 40 prisoners in one room, all shackled together. There was one cup of rice for all 40 people. I saw many people die, and thought I would die too.”

Van Chhuon’s remit did not extend to the protection of prisoners, but he persistently argued for Nai Kong’s life. After two months of negotiation, he was granted permission to collect him.

“When I saw Van Chhuon, I couldn’t believe it. He assigned a villager to take care of me. Today, I am alive because of Van Chhuon,” says Nai Kong, who has since become Kuok Snuol’s village chief himself.

Another villager, named Heng, was also keen to share his story. “The village teacher lived here the whole time and Van Chhuon kept the teacher’s identity secret. Later, when the Khmer Rouge came for me, he sent me out to grow vegetables,” he says. “They never found me. Van Chhuon saved my life, and many others.”

But when Vietnamese tanks rolled into town in 1979, signalling the beginning of the end for the Khmer Rouge regime, it was time for Van Chhuon to preserve his own life. “I ran into the jungle to hide,” he remembers. “People were taking revenge on the Khmer Rouge. Some village chiefs were hacked to pieces with machetes. Later, some elders came and convinced me to return. I did so but left Kuok Snuol after the rice harvest.”

Years later, in 1992, Van Chhuon requested the help of two men to build a house in Siem Reap. A few days later, 45 villagers showed up. It was a showing of respect for a man who, in his time as a village chief during the Khmer Rouge period, lost only one person. That was Ta Khan, the former commune chief who was murdered on Van Chhuon’s first day in his new role.

Says Van Chhuon: “I still regret his death to this day.”