A popular feature at funerals in Thailand, books of the dead also provide historians and chefs with a glimpse into a forgotten world

By Richard S. Ehrlich

Necrological literature may sound morbid and vampirish, but both Thailand’s wealthy elite and its humbler citizens are writing, publishing and reading millions of nostalgic ‘funeral memory books’ for free.

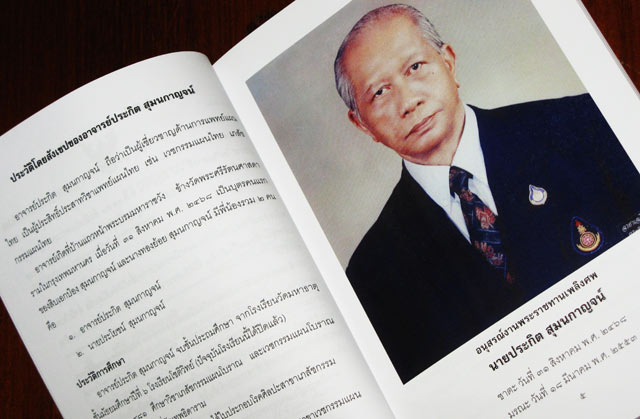

In print: the late Prakit Sumonkan’s funeral memory book describes him as an expert in traditional Thai medicine and the eldest son of three children

“These are books written about dead people,” says 83-year-old Tieng Nantoe, who wrote one when his younger brother died six or seven years ago. “It was only a booklet, so it did not take me many hours to write. He was about 55 years old and died from drinking alcohol, but in the book I did not say why he died. I just wrote that he had been sick. He was a colonel.”

Tieng’s other brother contributed to the booklet, which they hastily completed and printed at home before distributing it during the funeral.

Called nangsu anuson ngansop in Thai, these funeral memory books convey the ideas, thoughts and feelings of the dead, becoming a biography of sorts.

The text and photographs are not always grim, mournful or poignant. The publications can include eulogies, cheerful tales by loved ones, Buddhist prayers or descriptions of the deceased’s favourite recipes. The books are often illustrated with colour or black-and-white photographs displaying cherished family portraits, graduation pictures, weddings and, in some cases, meetings with celebrities, monks or royalty.

While the elite may produce opulent obituaries, bound in gold-embossed leather covers, others may plump for simpler, stapled pamphlets. Those who cannot afford to pay for such memorials opt to forgo the gesture or produce a short list of biographical details amid a selection of Buddhist aphorisms.

These books are not only read by mourning relatives and friends, but their captive audience can include scholars, chefs, artists and collectors, who have been quietly examining the volumes for historical references, traditional food preparation instructions, etymology, descriptions of travel, medical and herbal cures, quaint tales and gossip, and other eclectic cultural information.

Some high-end eateries in Bangkok, such as Nahm, boast their authentic cuisine is sourced from recipes found in antique cremation books. Chefs do not need to belong to an Illuminati-style Dead Recipes Society. They can simply visit libraries, museums, temples, shops or homes to find funeral books, or the homes of people who keep the documents for others to read.

“Southeast Asian collections in Western libraries have made an effort to increase the number of such works in their possession,” wrote Grant A. Olson in a 1992 edition of Asian Folklore Studies. “Recently, largely because of the rising cost of paper, cremation volumes are produced only selectively and are increasingly becoming an activity of the more well-to-do. Videos are becoming popular in Thailand, as they are in other parts of the world. While they are not yet handed out at cremations, videos of funerals are being sent out as mementos.”

Up until the mid-19th century, Thais traditionally gave out small gifts at funerals but then began offering something more personal and long-lasting.

The arrival of printing presses in 1835 popularised locally-produced books. One of the first cremation books appeared in 1881, when 10,000 copies were created for the double funeral of King Chulalongkorn’s Queen Sunanda Kumariratana and their daughter, who drowned when their boat overturned in the Chao Phraya River. That book included Buddhist chants and verses.

King Chulalongkorn, also known as Rama V, later became involved in shaping the contents of funeral books after he lamented that most people were merely filling their pages with stilted, confusing information.

In 1904, the king “proclaimed that these volumes, containing all this deep Buddhist philosophy, were not very enjoyable for most people to read. He requested that people begin to publish fables, Jataka (Buddhist) tales, and fiction,” wrote Damrong Rajanubhab, who managed Siam’s royal libraries at that time.

More recently, a library was established at Wat Bovornives to preserve funeral books for archiving, allowing curious families to learn more about their heritage and ancestry. From ashes to pages, Thailand’s tradition of funeral books means a person’s legacy can live on long after the cremation flames have died down.