Sharks, long placed at the top of the aquatic food chain, are traditionally feared by mankind, as evident in the popular Jaws franchise. The reality is reverse: human activity has led to more than a quarter of shark species around the world facing extinction.

Kathy Xu remembers watching the Canadian documentary film Sharkwater, which got her interested in shark conservation and the finning industry that was decimating shark populations around the world: “I used to be a full-time secondary schoolteacher in Singapore, and I used to like to talk to my students about environmentalism, animal welfare, conservation and stuff.

“I also heard about Lombok and how there was this fish market where sharks were landed daily. So I told my students I don’t want to just talk about these issues, I want to see if I can do something about it.”

Lombok is an Indonesian island east of Bali. According to Xu, Indonesia is the second-largest exporter of shark products, and Lombok is the second-largest shark market in the country.

Xu quit her job as a teacher and created her business The Dorsal Effect in 2012. Its goal was to create alternative employment for shark hunters in Lombok, where, she said, hundreds of sharks may be landed in the market on a good day. The market sells a variety of species, ranging from hammerheads to tiger sharks, while thresher sharks have become less common.

The Food and Agriculture Administration determined Indonesia produced on average 106,034 tonnes of shark products every year between 2000 and 2011. Many of the products are shipped to China, Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore and, more recently, Vietnam.

The practise of harvesting only the fins from the shark has decreased because of global awareness campaigns against shark fin soup, but Xu said the demand for shark meat has been rising over the past five years. People are less likely to recognise shark meat because it can simply be sold as fish and it is difficult to tell the difference.

While volunteering with the organisation Shark Savers, she felt the demand-side approach to stopping shark hunting did not fully address the problem of shark hunters needing a livelihood. “When I went to Lombok to talk with the [shark] fishermen, it’s not like they really chose to want to do shark hunting because they hated the sharks or because they thought there’s a great sense of joy in killing the sharks,” she said. “It was really just a livelihood in a geographical region, and they’re just well-placed with the right equipment and the right skills.”

Xu recounted some of the risks shark hunters face: “Some dangers involve them breaching international waters. They go to places where they’re not supposed to be hunting, but sometimes maybe they don’t know or they don’t realise or they just have no choice, they just really want to catch something…. And if they get caught, sometimes they get arrested. I did hear about this [shark] fisherman who was arrested and I think they managed to escape in the middle of the night in order to go back to their boats and run back to Lombok again.”

Some shark hunters recently have had to go farther out to sea for their catch, which Xu suspected may be due to climate change or overfishing. This leads the hunters to go farther into open ocean, which puts them at greater risk of being overpowered by the currents. They also face the possibility of their simple boats being broken down in the middle of the sea and sometimes having to wait for days for rescue.

When Xu approached the shark hunters about alternative employment, they said there were some good areas for snorkelling just off the fish market, and they were open to the idea of switching from shark hunting to eco-tourism.

The Dorsal Effect offers full-day boat trips run by former shark hunters who take people out to beaches and snorkelling spots near coral reefs around Lombok. Xu also takes the visitors to the fish market so they get to see the sharks as they are being hauled on land, an up-close education about the shark hunting industry in Lombok.

She also brings visitors to the shark processing plants. “[This] is the place where they dry the fins and the bones, and all the parts of the shark that they cut up, just so they understand that Lombok is a place where they don’t do shark finning. Shark finning is something that people commonly talk about, but actually Lombok is a place that does shark fishing, and all parts of the shark [are] actually utilised.”

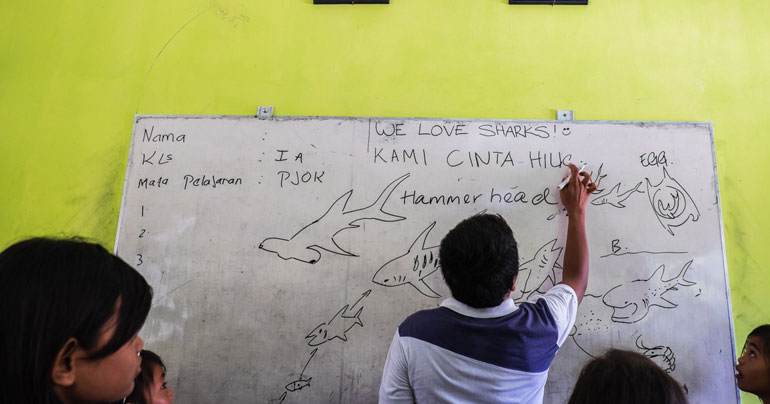

Xu sees school trips as the future of The Dorsal Effect. “[Students] learn about the complexities of the shark fishing industry, and they see how it’s not so simple. They get to see the human side, the fishermen, as well. So I think I’m going to continue to try to boost more trips… with the schools rather than with individual tourists.

“With the school trips, I really enjoy it for one because I used to be a teacher, and for another because I get a few days with the students. We don’t just go on the boat trip. I provide them with the opportunities to talk to and interview the fishermen as well so that they have a better understanding of why they’re doing this, what they used to do [and] what’s the incentive for them to want to change the trade that they’re doing.”

To learn more about The Dorsal Effect, visit thedorsaleffect.com.