Jakarta is not a city renowned for its aesthetic charms. With 9.6 million citizens clogging its arteries, traffic is reputedly the worst in the world and the city’s huge expanse comprises everything from burnished skyscrapers to corrugated iron homes. For Andrew Gaol, however, the city is simply one giant canvas.

an anti-corruption drive

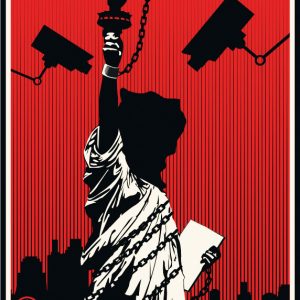

Working under the moniker Anti-Tank, Gaol is a street artist who posts political stencils and drawings all over the capital. His work is simple – often comprising no more than two or three colours and a short phrase – but thought provoking. One of his pieces features a dove carrying an olive branch in its mouth and a bomb in its feet, flying amongst a group of B-52 bombers. Another work melds together a hand grenade and a can of spray paint, with the implication that art is Anti-Tank’s weapon of choice.

“The power of art is that it brings energy to the viewer, be it positive or negative,” says Gaol. “For example, when Charlie Hebdo made their cartoon, everyone in Indonesia and the world made a hell of a noise about a simple drawing. This is how art can work, by provoking people. My work is a response to Indonesia’s current situation. I feel the need to use my art to comment on whatever is happening around me.”

However, in a world where an original work by the infamous British street artist Banksy can fetch upwards of $500,000 and graffiti has its own reality show named Street Art Throwdown, there is concern that the artform has moved away from its underground roots. It is a trend that is also infiltrating Southeast Asia, with some governments even commissioning artists to spruce up their cities.

Lithuanian artist Ernest Zacharevic completed six murals in Penang, Malaysia, as part of the 2012 George Town Festival. And the Singaporean government is a sponsor of the Singapore Street Festival, which will feature graffiti workshops for children aged 12 and over. The courses cost more than $2,000 for 12 lessons.

“I can definitely see [street art] commercialising,” says Kristopher Kotcher, a street artist in Ho Chi Minh City who has himself done work for Converse and BucketFeet shoes. “[There are people] who will start painting and try to get paid mural jobs within two months. You have to pay your dues first.”

Riksa Afiaty, a researcher and curator of street art at Ruangrupa Arts Laboratory in Jakarta, also feels that street art is moving away from its seditious roots and is being appropriated by the wealthier sections of society.

“You’ll find a lot of street art in the rich areas of Jakarta,” she says. “[But this art] doesn’t have any meaning. They are just trying to copy the American and European aesthetics.”

However, with the most established art scene in the region, as well as a rich recent history of collecting that began with the country’s founding father President Sukarno – who was a champion of the arts and an avid collector himself – Indonesia remains more in tune with street art’s doctrine than most of its regional neighbours.

A mural in Tangerang, just outside Jakarta, painted in the 1940s during Indonesia’s struggle for independence, reads: “Freedom is the glory of any nation. Indonesia for Indonesians!” More recently, Apotik Komik, a visual arts collective based in Yogyakarta, Java, became well known in the 1990s for their DIY social commentary pieces fashioned from cardboard and house paints. They favoured irony and subversion over more explicit messages, as exemplified in their mural “Ongoing Illness”, which shows a group of dancing doctors rolling away a wheelchair-bound patient.

Amien Subandono, who works under the pseudonym Menaw, makes art that takes on a surreal, almost disturbing quality. He paints bug-eyed cartoons that eye the viewer uneasily, or blue skulls with oversized cigarettes dangling from their mouths. Subandono says he loves the fact that he “can make connections and build a brotherhood with artists from different cities in Indonesia”, and that sense of community pervades his art. Rather than kowtow to Western artists, he draws from a unique local identity.

“My art uses characters from traditional Indonesian culture,” says Subandono. “I take wayang puppet theatre and the old-school Indonesian masks, for example, to combine the old and the new.”

Meanwhile, Jakarta’s Andi Rharharha uses duct tape to make his street installations. His fixtures can be removed within minutes, but his message is enduring. “My goal is to involve as many people as possible to create a network of social movement in the streets,” he says.

In one piece, Rharharha simply spelled out a quote from Indonesia’s first president and national hero Sukarno: “The Republic of Indonesia does not belong to… any religion, nor to any ethnic group, nor to any group with customs and tradition, but [is] the property of us all, from Sabang to Merauke.”

At the other end of the spectrum, when former Indonesian president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono won the World Statesman Award in 2013, Rharharha had protesters hold signs and lay down next to an arrangement of duct tape that read: “Indonesia Menangis” (Indonesia Cries).

While his work frequently takes aim at authority, Rharharha is also pragmatic enough to embrace Indonesia’s well-documented obsession with social media.

“The big issue in Indonesia right now is corruption,” he says. “We’re using Twitter, Instagram and Facebook to inform and mobilise people.”

As street art begins to move away from the counter culture in much the same way as tattoos or dance music, a certain breed of newcomer can be relied upon to exploit it for notoriety or financial gain.

“Graffiti and street art are the rock’n’roll of visual art, so of course they can be both rebellious and a way to make a buck,” says Caleb Neelon, co-author of Street World: Urban Art and Culture from Five Continents. “But good political street art makes its way around the world on the internet in a matter of hours.”

It would seem that authenticity is at stake, but to many of Indonesia’s underground tastemakers artistic intent will always be key. “The popularity [of street art] is inevitable,” says Rharharha, “but the commercialisation of public space is something we have to control and fight. Street art needs to be an inspiration to the city. It needs to spread a message of humanity.”