Stealing With The Eyes details Buckingham’s research and pursuit of traditional Tanimbarese sculptures while encountering captivating people and getting caught up in folklores and witchcraft along the way.

The book also questions the practice of anthropology and the effects it has and how this experience ultimately led Buckingham to quit his anthropological studies

You provide excellent and detailed descriptions in the book of your work, the people you met, the adventures and misadventures you had. Can you give us a brief insight into that – and what life was like living in the Tanimbar Islands (without giving too much away)?

There is so much to say here. My main experience of Tanimbar was one of disorientation. I think I say in the book that to really commit to being somewhere else, you need to succumb to the peculiar logic of that place. And this can be very strange and puzzling. Let me take an example. Witchcraft beliefs are very strong in Tanimbar. When I was in Tanimbar, I met with witches and their victims, I was myself possessed and then exorcised – not particularly successfully, it turned out. And I spent many hours hearing stories about witches and the havoc that they can cause. With my rational head on, of course I don’t believe in the literal existence of witches. But having said this, it was almost impossible to function in Tanimbar without taking witchcraft beliefs into account. At the very least, matters of social delicacy demanded a certain degree of care and circumspection when it came to matters of witchcraft and black magic. When you start to take these things into account so that they affect your daily life, your experience of the world begins to change

Three things above all stand out when I think back to my time in Tanimbar. The first is the immense patience and generosity of my Tanimbarese hosts when my presence there must often have been burdensome and annoying. The second is the sheer exhilaration of finding myself unanchored, adrift and disorientated – the curious delight of realising I didn’t have a clue what was going on around me, and of trying to work it all out. And the third is the intense loneliness of living in a world that was culturally alien, a world I comprehended badly and that I was often only barely competent to navigate. This strange loneliness, the days spent speaking only Indonesian, the sense of being cut off from my own roots, are all a part of what made me a writer. After several months in Tanimbar, I borrowed a typewriter, sat down at my desk and started to bash out stories, fragments and plans for future books. For this, at least, I owe Tanimbar an awful lot.

You had a brief yet very intimate relationship with the place and the people of Tanimbar, and expressed your yearning to go back there. Would you like to visit again or leave it as a romantic notion of what was?

I’m not sure that my recollection of Tanimbar is particularly romantic. One thing about actually spending time somewhere is that you quite quickly lose your romantic preconceptions. In some ways, Tanimbar was a hard place to be. But it was a fascinating one. You are right that it was, for better or worse, a curiously intimate relationship. And this relationship with Tanimbar ended up having a huge effect on the course of my life. Tanimbar got under my skin. It changed how I saw the world.

As for whether I would like to return, I think I would, although the prospect is daunting. One reason I’d like to go back, as I say in the book, is that I am interested – and a little bit frightened – to know what people in Tanimbar themselves might make of what I have written. How does what I have written stand up for those who lived and who still live there? This is both an interesting question and perhaps a necessary one.

Very early on in the book, we discover the reason behind the title and find out what ultimately led you to quit the field of anthropology. Do you still feel the same way about anthropology?

I have very mixed feelings about anthropology. When I first came across anthropology as a rather hapless art student, I fell in love with the subject. What enchanted me was the sheer malleability of human life and culture. Anthropology made me realise that things I took for granted, the things I considered to be common sense, were far less obvious and natural than I had always assumed. In its careful exploration of difference, I think that anthropology still has the power to undermine Eurocentric or Western-centric views of the world. It can show us that there are other possibilities for how to live. It can give us new ways of imagining our lives. It can put into relief how culturally bound are the assumptions we make about what it is to be human, and can awaken us to the narrowness of the ideas we hold about how we can, should or might organise our lives.

At the same time, anthropology is an enterprise that is thoroughly entangled with the legacy of colonialism, so it is always a pretty problematic business. As an academic discipline, anthropology has changed since I first studied the subject: it is now much more self-aware when it comes to the ethical and political complexities involved. Anthropology has got a long way to go before it shakes off its colonial past – if it can do so at all. But at the same time, without diminishing the seriousness of these issues, it still has a lot to say and to contribute.

Your encounter with the French traveller and the Dutch journalist in Tumbur depicts a stereotype that we have all come across – one with an uninformed notion leading to cultural exoticism. What are the biggest issues with these preconceived expectations?

These are two extreme cases of cultural exoticism that I explore in the book, but there are more subtle cases too. I am fairly upfront about confessing my own culpability here as well: my experiences in Tanimbar, how I thought about these experiences, and even my desire to go there at all, were all themselves underpinned by a kind of cultural exoticism.

But then, I don’t think any of us truly escape cultural exoticism. For my friends in Tanimbar, the West was itself a place of exotic strangeness, the subject of all kinds of preconceptions. In the book, I am fascinated about these crosscurrents, where dreams and fears of sex and death – the exotic, ultimately, is always tied up with ideas of sex and death – seem to swirl together.

I used to tell my creative writing students that everywhere is exotic from the point of view of somewhere else; but on familiarity with elsewhere, we always find it is never as exotic as we hope or dream. J. M. G. Le Clézio, in The Book of Flights, writes that we always hope to arrive in a place where people wear owls on their heads, but we never do. Exoticism gives birth to disappointment. Nevertheless, once you get over this disappointment, once you realise that all places are pretty much the same, then you can start to see that different places really are different, just not in the way you had imagined.

The problem with exoticism, in the end, is twofold. We imprison others inside our notions of how we want them to be different, and we blame them when they don’t live up to these notions. But in doing all this, we also become inattentive to the real, and often fascinating, differences there are between us.

Do you think that the logging and deforestation fears expressed by one of the sculptors in Tumbur will eventually come to pass? Or worse, have they already come to pass?

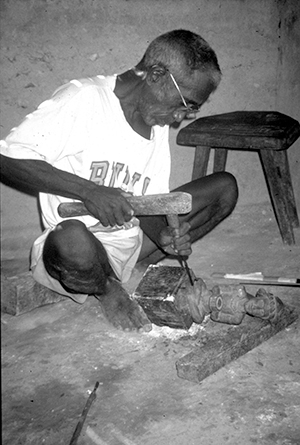

From what I know, the slow-growing kayu hitam – a kind of ebony – from which many sculptures were made in Tumbur is now more scarce than it was, in part due to logging and deforestation. Of course, deforestation has much bigger implications for local communities and for the environment than just its impact on the practice of artists. People in Tanimbar knew this: there was a sense amongst local people that the proper stewardship of the forests was a matter of survival, not just for the wood-carving industry, but also for the Tanimbarese way of life as a whole.

Having said this, although there has been some decline, Southeast Maluku has so far avoided the aggressive deforestation of some other parts of Indonesia, largely due to its remoteness.

Can you talk about where you are and what you’re doing these days?

Just at the moment, I’m back in the United Kingdom. After returning from Tanimbar, I studied for an MA, started a PhD in anthropology, dropped out of the PhD, spent time living in Buddhist communities, started and finished a PhD in philosophy, wrote some books, got tangled up in Chinese philosophy and literature, and worked in universities for several years, teaching both philosophy and creative writing. A couple of years ago, after the death of my long-term partner, the museologist Elee Kirk – who took the wonderful photo of the Tanimbarese ancestor figure made by Damianus Masele, pictured towards the end of the book – I resigned my university post. Since then I’ve been freelancing.

At the moment, I spend my time writing, teaching and setting up various interesting projects. I’ve just set up a project called Wind&Bones with my fellow writer Hannah Stevens, and we are doing all kinds of things related to writing here in the UK, in Bulgaria and – in a couple of months’ time – in Myanmar. I was working in Myanmar for several months last year, so I’m currently brushing up my rudimentary Burmese language.

Finally, I’m also cooking up another non-fiction book with my agent. We’re at proposal stage, so I’m not going to say any more at the moment, but it should be a lot of fun if it comes off.