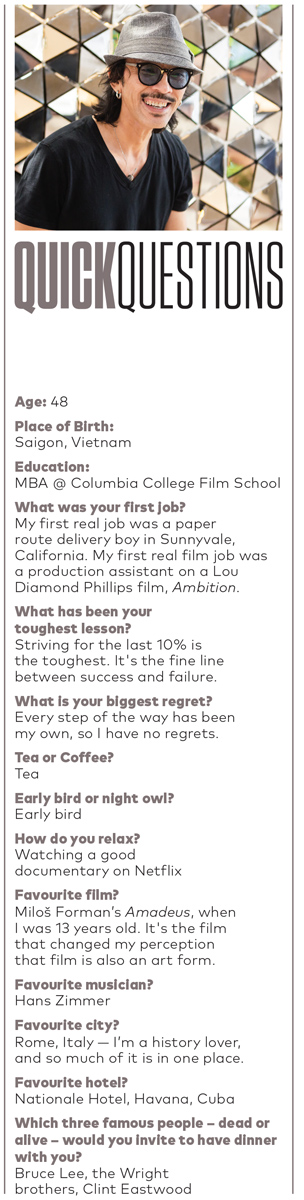

Timothy Linh Bui still has VHS tapes of the first movies he made. They were snappy action-packed shorts filmed on a camcorder in his parents’ backyard near California’s Silicon Valley.

“I remember a friend of mine and I, we created this detective story… He had a hat and a trench coat on and was looking for this killer,” says Bui of an early ’80s effort. “There was no editing machine at the time, so you kind of had to really plan everything. You have to plan ahead where you shoot this. You stop it. You change the camera angle. You shoot it again. So, when you watch it, it’s all [been] edited in your head already. I guess that was the first time I was thinking that way.”

Roughly 40 years later, Bui thinks about these details for a living – but instead of producing in his parents’ backyard, he works in their home country of Vietnam, where he and his business partner Anh Tran launched Happy Canvas Film in 2016.

The Ho Chi Minh City-based company does everything – from writing screenplays to producing and delivering films to audiences. Their current challenge is to develop a Vietnamese version of the long-running US television show The Bachelor, which requires slashing the salaciousness and building a platform for genuine relationship-building to appease the local audience.

Nine people, including the two co-founders, run the company, which also works hard to develop young, local talent. It runs on an annual budget of just $200,000. Their aim is to propel the local industry by creating locally relevant content using “universal storytelling”, meaning the storyline is cross-culturally engaging.

Bui wants Happy Canvas productions to share realistic insights into the Southeast Asian country with the rest of the world.

“There are a lot of bright minds, a lot of creative kids here coming out of film school, but without the proper [understanding of story] structure,” Bui says. “So we went out, we hired a team of young, very creative individuals, and we spent the first three or four months honing the craft of understanding the structure and then applying it into stories that are localised.”

Growing up, Bui’s primary exposure to Vietnam was through Hollywood war films that left him with a derogatory view of the communist country. The film industry was largely alien to him, despite Hollywood being a coin-toss away, his fledgling backyard movie productions and his joining a high school film club. Working at his parents’ chain of VHS rental stores was his only connection to the industry. When he graduated from high school – and from his summer job tending his parents’ shops – Bui moved to Los Angeles for business school.

“Being in LA, driving around, you come across film productions, and I thought, ‘Oh, that’s very fascinating, there are people who actually do this for a living’,” he says. “From there, I dropped out of business school and enrolled in film school.”

That decision was a radical turning point for Bui. He soon found himself interning as a production assistant on a Lou Diamond Phillips film, a gig that led to mentors and more opportunities to gain firsthand experience on sets.

In the mid-’90s, Bui flew with his brother Tony Bui to Vietnam for the first time to film Three Seasons, the first-ever US-funded film made entirely in the country, which they co-wrote. It was then that Bui fell in love with Vietnam and began challenging the sentiment ingrained in much of the media he had been exposed to. In 1999, the film, about a US veteran’s return to Ho Chi Minh City, stole the audience award, the cinematography award and the grand jury prize in one fell swoop at the Sundance Film Festival.

“Three Seasons found some success, opened some doors, and then I went on to make a film called Green Dragon,” says Bui. The 2001 film about Vietnamese refugees to the US starred Patrick Swayze and Forest Whitaker. “Those were kind of, I think, the sparks for me getting into the film industry.”

But there was a divide between his newfound love for Vietnam and cinematography.

“There was no industry [here] back then. We were shooting in Vietnam with these movies, but they were both American-financed films,” he says. “It wasn’t for the market [here].”

“I was at the crossroad right there. Do I go back to the US and focus there, or begin in this emerging market?”

Timothy Linh Bui

Over the years, other filmmakers travelling to Vietnam kept him abreast of the local production scene, which has been growing over the past few years, Bui says. In 2013, he and Tran created Happy Canvas as a US entity, but then Bui returned to Southeast Asia to produce a ghost story, The Housemaid. Despite tight regulations on ghost films, the movie premiered in Vietnam in 2016 and became one of the company’s greatest achievements.

“We broke some barriers… Ghost stories weren’t allowed [here]… [A]t the end of the movie, you would have to say somehow that the ghost was a fake; in The Housemaid, the ghost existed,” he says. It went on to become a top-grossing picture in Vietnam, and also found success in Latin America, the UK and elsewhere. Happy Canvas is even collaborating with a US company on an English-language remake.

With The Housemaid, Bui feels he showed how local filmmakers could use universal storytelling to draw interest to Vietnam.

“I was at the crossroad right there,” he says. “Do I go back to the US and focus there, or begin in this emerging market?”

Tran and Bui chose the latter when they established Happy Canvas as a Vietnamese company. It has since been on a production schedule of roughly three films a year, and Bui regularly attends pitch fests to find young screenwriters with potential – future filmmakers who need mentors like the ones Bui looked up to in Hollywood in the ’90s.

Almost immediately after they launched, Happy Canvas faced one of its first hurdles.

“Vietnamese films were going through a period where there was a lot of fear in the industry that the audience was backing away from Vietnamese content,” he says. Because the industry was so young, the box office was flooded with low-quality slapstick comedies. Locals were going to Hollywood films instead.

“They’re watching films that are well put together with sound design and lighting and so forth, so there became a backlash [from the audience],” Bui says. “The box office was going down for Vietnamese films drastically, and… it was a wakeup call for the industry. Like, wait a minute, we’ve gotta really take our time in developing. We can’t just put anything out.”

Happy Canvas overcame the lull by continuing to cultivate well-planned films, which are more time consuming but pay off at the box office, Bui says – but they’ve had to peddle hard to convince still-sheepish studios to take risks on their films since the industry scare.

But as more highbrow films are getting produced in Vietnam, the competition has become a key driver, says Bui: “Competition breeds success… and there is that underlying competitiveness now.”

Bui sees signs of increasing quality everywhere in the Vietnamese film industry: sound, lighting, visual effects and even stunt work. The previously limited talent pool is percolating. It’s a perfect storm for Happy Canvas and the film sector. As the company seeks investing partners, Bui says he expects to hear better and better pitches as he scouts talent in the coming years. Over the next two years, he plans to train up his team to be able to produce without his oversight and to increase production beyond three films a year – and hopefully branch further into television as well.

And it’s all been about giving others the mentorship and training that turned his backyard hobby into a profession, he says: “For me, it’s exciting because I know what it’s like to be on the other side, to be on a set and have someone in a sense take you under their wings or believe in you and create that opportunity. So that’s what I try to do here.”