Climate anxiety is not gender equal.

According to a recent survey on climate change perceptions Southeast Asian women express stronger climate concerns than their male counterparts.

Around the world, analysing climate phenomena through a gendered lens is gaining more traction than ever. And understanding these different perceptions more deeply is necessary for acknowledging the rights of climate justice across various groups and avoiding masculine domination in shaping climate policy discourse such as complicated data projection, profit-driven economic modelling, and search for quick-fix technologies.

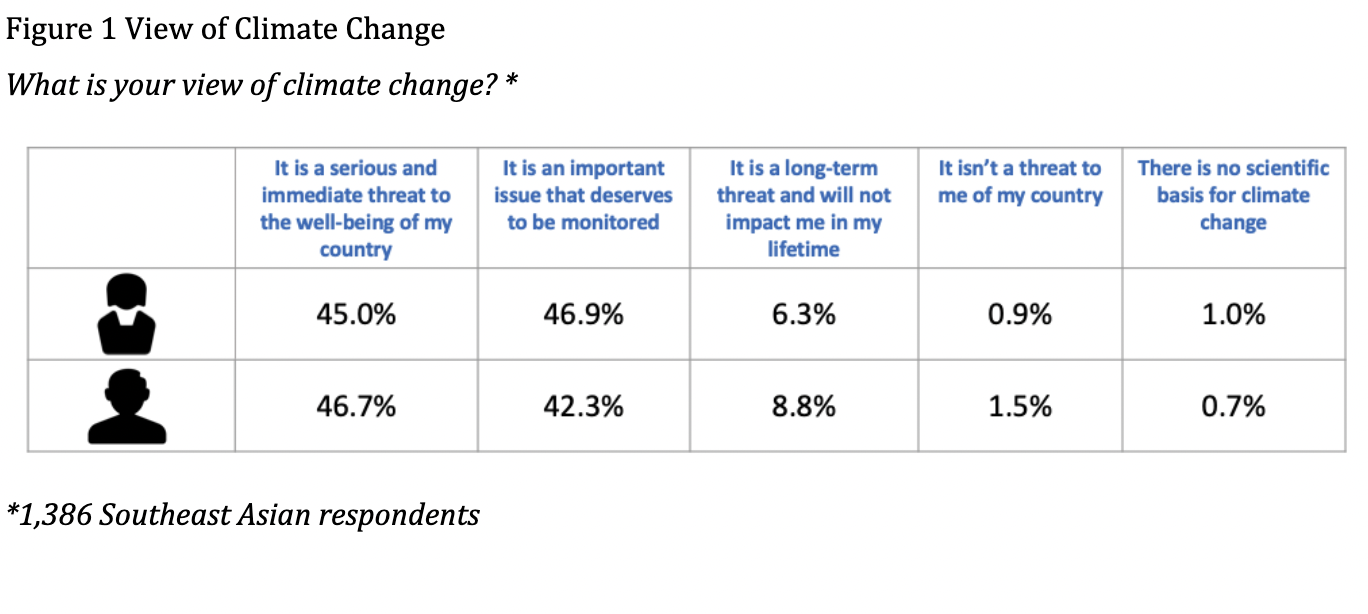

According to the Iseas-Yusof Ishak Institute, 91.9% of women in the region view the issue as an “immediate threat to the well-being of their countries” and “an important issue that deserves to be monitored.” Meanwhile only 89% of men in the region agree with those views.

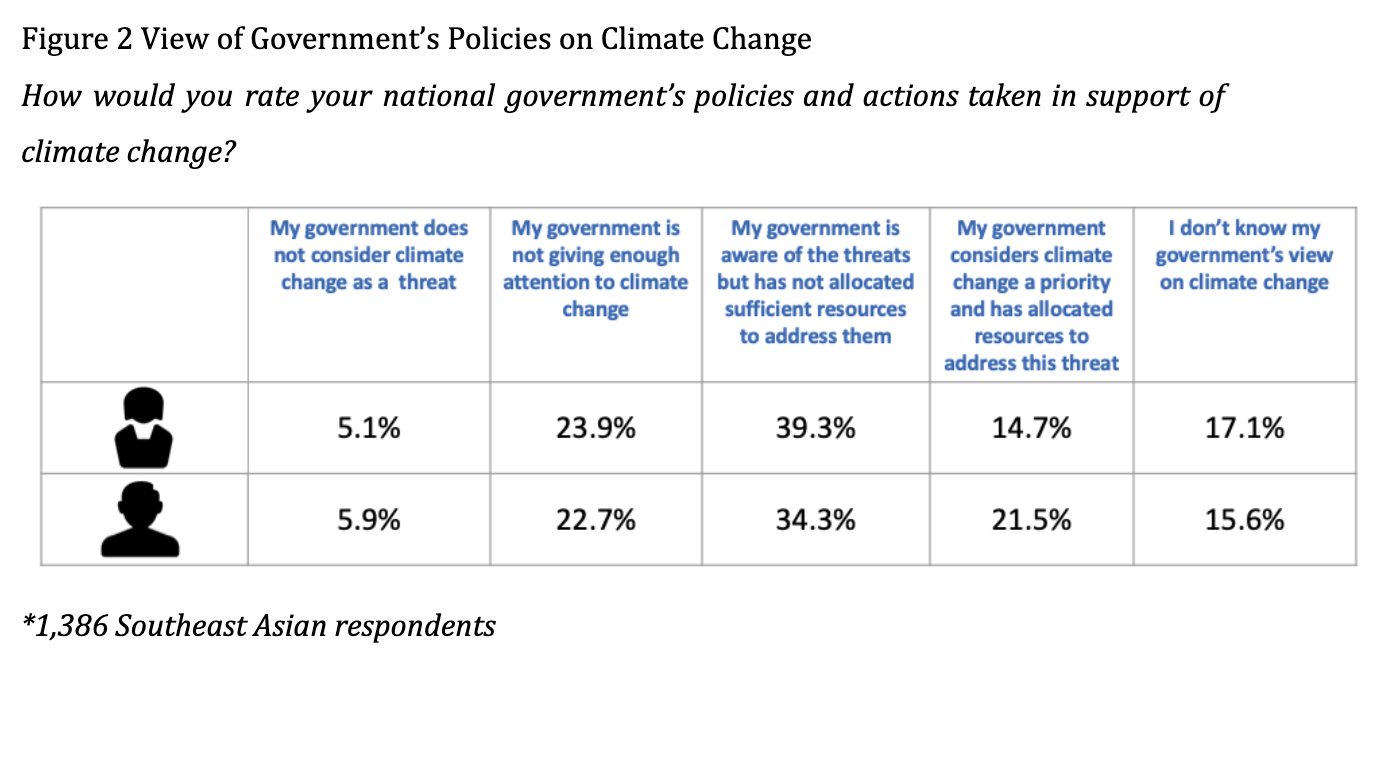

Women in the region are also more likely to report concern over their government’s response to climate change and climate threats, worried that their government’s have not allocated sufficient resources to address the issue.

The study is not an isolated case. Many global reports indicate the same findings on gender and climate anxiety.

As the climate crisis becomes increasingly urgent, governments in Southeast Asia risk overlooking how it is inherently linked to the equally urgent issue of gender inequality.

When Typhoon Haiyan struck the Philippines in 2013 and recorded a death toll of more than 6000, the global community saw the impact of this extreme climatic event on women.

The Amihan Federation of Peasant Women, a leading research group on gender-sensitive policies, estimated that 64% of the Typhoon Haiyan death tolls were female. . Even a year after the super typhoon impacts receded, women in the affected areas still struggled with the social and financial effects. Many women were found living in tents and temporary shelters without enough nutritious food and stable jobs.

Southeast Asia is among the world’s vulnerable regions to climate change due to its geographic exposure and high dependence on climate-sensitive sectors such as agriculture, forestry, and fisheries.

The Global Future’s poll on eco-anxiety in Great Britain in 2021 found that 45% of female participants reported higher levels of worry about climate change compared with 36% of men.

Similarly, a study on Climate Change in the American Mind in 2019 by the Yale Program on Climate Communication, found that women have higher risk perceptions that climate change will harm them personally today, with ramifications for future generations of people.

Climate anxiety might not yet be perceived as a social phenomenon in Southeast Asia and not officially recognised as a mental disorder globally, but as the impact of climate change is escalating it seems unsurprising for certain vulnerable groups such as women, people with disabilities, youth, and the elderly to feel distress about the future of the earth and their limited capacity to cope with the climate crisis.

.

Women in Southeast Asia are already disadvantaged in many ways. Given certain cultural norms and an equitable sharing of roles, resources, and representations, women are often vulnerable.

According to the International Labour Organisation in 2019, Six Southeast Asian countries – Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, and Thailand – have recorded under 60% of female employment rate, below other Asia-pacific major economies.Although other regional countries such as Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam recorded a relatively higher female employment rate, they continue to have a considerable number of women in informal and low-skilled jobs that make them susceptible to job losses.

As effects of climate change begin taking shape across the globe, women’s jobs will be more vulnerable. A version of this was seen during the pandemic, as women represented approximately 91% of manufacturing job losses, and 58% of overall job losses in Thailand.

The State of Gender Equality and Climate Change in ASEAN report highlights that women in the region make up a significant portion of the workforce in the sectors exposed to climate change such as agriculture, fisheries, and forestry.

Female farmers are more likely than men to face water, food, and land insecurities in regards to climate change due to their caregiving roles.

Meanwhile, 92% of those who benefit from carbon-intensive industries, such as crude, petroleum, and natural gas, are men, according to an outlook published by UN Women. The same report states that men are also seven times more likely to be employed under mining and quarrying industries. Thus, men are mostly responsible for the climate crisis.

Women face more barriers to their male counterparts when it comes to pivoting to new jobs. For instance, when a climate disaster happens in a village, both men and women will lose their incomes. However, unlike men who can move more swiftly to find other jobs in cities, women’s mobility is somewhat restricted due to their caregiving roles to their families, children, and communities.

Feelings of distress from climate impacts could make women worse off in several ways. Women with child-bearing roles in particular might be more concerned with loss of food, reduced household supplies, and disruptions on healthcare access for their children which may lead to chronic mental stress compared to men who are not involved in caregiving roles. Women are perceived as protectors of the household while men are away at work. Such a role can become an extremely dangerous task in the event of a natural disaster, and only becomes more unsafe in the case of pregnant women.

Women are also misrepresented in various decision-making processes at the top level. According to the OECD, Women in Southeast Asia held only 20% of the region’s parliamentary seats in 2018, although there is a great deal of variation amongst the countries: 30% in the Philippines, 28% in Laos, 27% in Vietnam to a mere 5% in Thailand and 9% in Brunei. This lack of representation will make it hard for women to put forward gender-sensitive policies and laws that can enhance sustainable development goals and climate actions.

Regardless, gender inequality in climate affairs can appear more skewed when viewed more closely. In the Philippines, four government departments are responsible for the country’s natural disaster risk management. Between the years 1986 to 2017, only 12.5% of all appointed secretaries in the Department of Science and Technology were female, and only 5.6% of all appointees in the Department of Environment and Natural Resources. None of the appointees in the Department of Interior and Local Government and the Department of National Defence were women.

Concerns about climate change and gender inequality have started to occupy various regional agendas. This year, ASEAN published the State of Gender Equality and Climate Change in ASEAN to examine the impacts of climate change, vulnerability, and the adaptive and mitigative capacity of women in the region.

Last year, ASEAN also adopted the Regional Framework on the Protection, Gender, and Inclusion and in Disaster Management (ARF-PGI). The framework highlights different policy strategies against gender-based violence and the general exclusion of women, children, youth, elderly, poor, and disabled in disaster management. It also provides evidence that such issues are indeed present in Southeast Asia’s existing climate. While the frameworks have successfully amplified awareness on gender inequality and climate change among policymakers, these frameworks can only serve as guidelines as its adoption remains at the discretion of member states.

There is an increasing recognition that gender equality and women’s empowerment are critical to socioeconomic development. Due to worsening factors of climate change, Southeast Asian governments need to step up their game to future-proof their women from climate distress.

Melinda Martinus is Lead-Researcher at the ASEAN Studies Centre and the Climate Change in Southeast Asia Programme at Iseas-Yusof Ishak Institute.

Beatrice Riingen is Research Intern at the Climate Change in Southeast Asia Programme at Iseas-Yusof Ishak Institute.