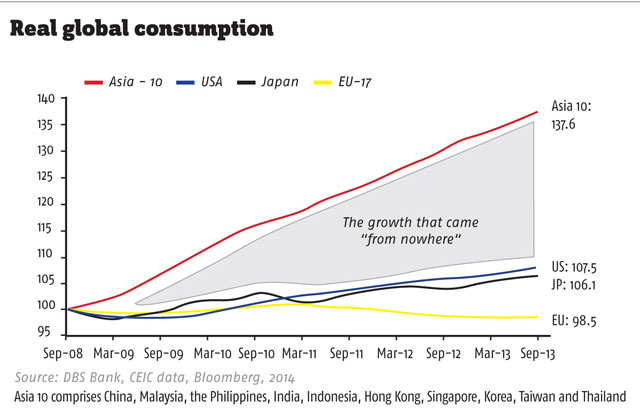

What we are seeing today is possibly the most fundamental and revolutionary transformation of Asian economies: the global middle class expanding eastwards. Thanks to economic and demographic growth, global consumer demand has shifted dramatically towards emerging markets – and that shift will continue.

Southeast Asia is at the heart of this development: Observers already call the region the next frontier for consumer growth. Asean member states have dramatically outpaced the rest of the world on growth in gross domestic product (GDP) per capita since the late 1970s.

Income growth has remained impressive since the beginning of the century, with annual gains of more than 5%, according to consulting firm McKinsey.

“The growth of the emerging middle class has made Asean a growing hub for consumer demand,” said Mohit Das, head of McKinsey’s Asia Consumer Insights Centre. “This will have a big impact on economic development, especially in markets such as Indonesia, where consumer demand already accounts for 57% of GDP.”

Today, some 67 million Southeast Asian households are part of a new affluent class, with incomes exceeding the level at which they can begin to make significant discretionary purchases. This number could almost double to 125 million households by 2025, Das added, making Asean a pivotal consumer market in the future.

Within the region, Indonesia is likely to profit most, not at least due to its sheer size. “Indonesia is the most obvious one, whereas the Philippines is the potential dark horse,” said Santitarn Sathirathai, an economist at Credit Suisse in Singapore.

“The Philippines and Indonesia are more in a group where you have a lot of poor people and lower income people. So you have that initial entrance stage” for the emergence of a middle class, he added.

With its almost 250 million inhabitants – the fourth most populous nation worldwide – attractive demographics and a strong investment climate, Indonesia “represents a more compelling opportunity than many others”, a report by management consulting firm Boston Consulting Group (BCG) said.

Its middle and affluent class population is expected to double to more than 140 million by 2020, “making this period a significant opportunity for businesses seeking strong growth”.

“Multiple other Asean countries will see rapid growth as well,” said Tuomas Rinne, partner and managing director at BCG in Bangkok. “In particular, we remain optimistic regarding the long-term outlook for Vietnam where we expect the middle class […] to grow by 150% between 2012 and 2020.”

Over the same time period, Myanmar’s middle class will nearly double to 10.3 million. “Companies should enter now but recognise that Myanmar is a long-term play. The first mover advantage will not last long,” said Daw Win Win Tin, managing director of the country’s largest retailer, City Mart.

“If you come in late, the cost to win will be much higher. In other words, they need to hurry to go slow.”

At the same time, investments and growing domestic consumer demand will make Asean nations less dependent on exports. “Domestic demand will be an important driver for future growth,” said Rajiv Biswas, chief economist Asia-Pacific at IHS in Singapore. “The focus is gradually shifting from relying only on the US, the European Union and Japan, which will be still important, but also recognising that trade among their own countries will be crucial.”

The wave of new wealthy citizens potentially has positive effects in many of the region’s industries. “Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam […] have seen quite strong growth in consumer demand. This is encouraging investment by large multinationals in the consumer products sphere,” Biswas said.

“Some of the largest multinationals think that these countries are some of their fastest-growing markets, also due to their very significant size.”

Asean’s automotive sector is seen as one of the most promising industries to profit from the emerging middle class. Almost half of Indonesia’s and the Philippines’ citizens have no car, while both countries as well as Thailand rank among the top ten countries globally for the intention of their citizens to acquire a car within the next two years, according to market research company Nielsen.

“For many of these consumers, car ownership is the ultimate symbol of how far they have come and the success they have achieved.”

The world’s second-largest automaker, Germany’s Volkswagen, so far not very visible in this part of the world, now sees Southeast Asia “as a key growth region” and aims to increase its market share in the region “quite significantly” in coming years.

The services sector is another area that will benefit disproportionally from new affluent customers, in particular the banking and insurance industries, but also tourism, retail and telecommunication.

With rising wealth consumers also see a bigger need to secure their social position. “The insurance sector is expected to benefit from the rise in the middle class in a major way, but consumers need some more time to change their perception of insurance products and recognise the need to protect themselves,” BCG’s Rinne said.

Apart from that, luxury goods come into focus. “When consumer’s graduate to the middle class, their consumption habits change. They start to afford convenience, comfort and indulgences,” he added.

Asean countries are no exception. “Southeast Asia has become the rising star of the Asia-Pacific region,” a study from management consulting firm Bain said.

Growth in the luxury market amounted to 11% last year, interestingly not only in its historic core of Singapore, where every tenth citizen is a millionaire, but in Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam and Thailand as well, according to the study.

Luxury-product manufacturers are even focusing on Cambodia, still one of the poorest countries in the world.

Porsche and Rolls-Royce entered the market recently and will open up showrooms in the country’s capital this year. “In Southeast Asia, there is clearly a correlation with other regions between rising disposable incomes, middle classes, urbanisation and demand for branded mid-level and luxury goods,” said Deborah Aitken, senior luxury analyst at Bloomberg Industries.

“The luxury sector is growing 1-2% above GDP, as middle and higher incomes expand at faster rates than overall GDP.”

However, the prospects for the region are not all rosy, and challenges remain. “Economic development often goes hand in hand with urbanisation. As consumers become wealthier, they start owning cars and can afford to live in larger dwellings,” Rinne stressed.

“These changes will put a heavy strain on cities that need to meet the resulting construction and traffic challenges. Forward-looking urbanisation plans and massive infrastructure investments are needed.”

With the share of wealthy citizens in the region surging, increasing energy demand also poses huge risks to the environment. “If Asia’s expanding middle-class citizens all aspire to Western living standards through the Western model, the strain placed on our global environment could prove disastrous,” Kishore Mahbubani of the National University of Singapore wrote in a study.

Without radical changes to Asia’s energy mix, oil consumption will double, natural gas consumption will triple and coal consumption will increase by 81%, almost doubling global carbon dioxide emissions, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) warned recently.

What’s more, there is no guarantee that Asean member states will continue to evolve as a high-income society once they have reached middle-income status. Countries fall into the so-called middle-income trap if they are unable to move up the value chain, failing to develop from a low-cost to a high-value economy, making it difficult to compete with both low-cost and high-income nations.

“It appears highly possible” that several countries in Southeast Asia including Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand are at risk to fall into the middle-income trap, the ADB said.

To avoid such stagnation, governments must strengthen the industrial basis, foster research and development, and in particular invest in education to encourage innovation in their economies. However, education systems do not evolve in tandem with the region’s development. In Indonesia and Myanmar alone, McKinsey projects an undersupply of nine million skilled and 13 million semiskilled workers by 2030.

Another worrying trend is Asia’s unique ageing process. For example, the US took 72 years for the population of ages 65 and over to double from 7% to 14%. Most countries in Southeast Asia are expected to take only 20 to 25 years for the same process, according to the Malaysian central bank.

“Asia will have a much shorter timeframe to ensure an adequate social safety net is in place to support an aged society,” the bank’s assistant governor Donald J. Jaganathan said.

And even if all these challenges are mastered, there is still the danger that significant numbers of Asean citizens will be left behind. While poverty in Southeast Asia has fallen dramatically over the past two decades, income inequality is on the rise almost everywhere.

“High and rising inequality can curb long-term growth because it leads to a waste of human capital, reduces social cohesion, hollows out the middle class, undermines the quality of governance and increases pressure for inefficient populist policies,” Juzhong Zhuang, deputy chief economist at the ADB, wrote in a research paper published in April.

Recent analysis by the ADB shows that if inequality had remained stable in the Asian economies where it increased, the same growth in 1990 to 2010 would have taken 240 million more people out of poverty, he added.

“It is an inevitable result of the emergence from very low income levels that there will be some increases in inequality,” IHS’s Biswas said. Still, he remains optimistic.

“You need rapid growth of the urban middle classes as this is the first step to broader economic development. The benefits of that will over time flow through society.”