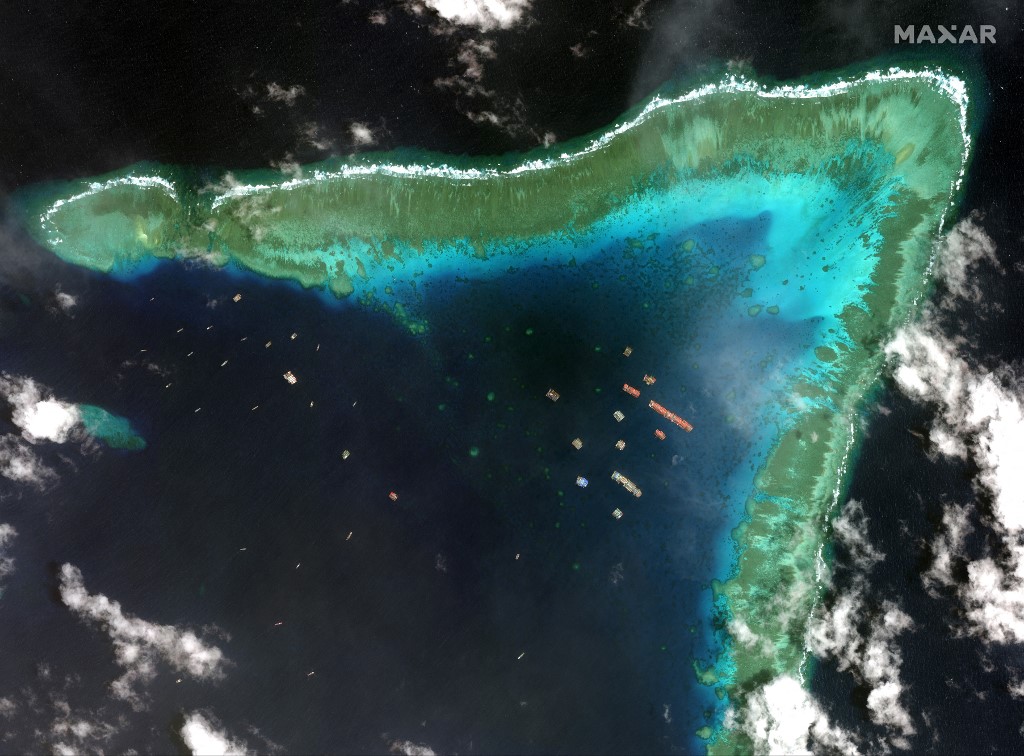

The fleet of Chinese fishing vessels huddled together in loose formation, 220 boats tucked quietly in the bend of a boomerang-shaped coral reef in what many call the South China Sea.

They first appeared in December 2020 at the place called Whitsun Reef, a natural formation at the heart of the hotly-contested Spratly Islands, some 35km west off the coast of the Philippines.

Hua Chunying, a Chinese Foreign Ministry spokeswoman based in Beijing, told the press late last month that the fishing vessels are simply taking shelter from strong winds – but no one knows for certain why the vessels are there. They’re not fishing, and they haven’t moved much. They just sit, anchored in a stretch of sea claimed by five different nations: China, Taiwan, Vietnam, the Philippines and Malaysia.

In other seas, 200 odd fishing vessels may not be much to worry about – in this one, where Chinese ‘fishing militias’ have acted as a vanguard for the state’s territorial goals, a fleet like this was cause enough to scramble the Filipino air force. Now, as jets routinely monitor the fleet, fears are mounting in the Philippines that Chinese leaders are looking to start construction on a new artificial island to further entrench a national claim to the controversial reef.

The search for answers over China’s long-game in these waters is more often linked to lucrative subsea oil and gas deposits, as well as control over a waterway through which a third of the world’s maritime trade flows. But according to Rashid Sumaila, professor of ocean and fisheries economics at the University of British Columbia and director of the Fisheries Economics Research Unit at the UBC Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries, perhaps the sea’s most overlooked asset is its living wealth.

“There’s too much fishing effort there. [China and Southeast Asian nations] need a lot, as there’s a large population [of fish] around the South China Sea. That is where you have the political games being played,” he told the Globe. “We tell [claimants], these fish are so important for the populations.”

As China attempts to consolidate its claims to the sea, long-standing rumours of food insecurity swirl in the country. In August 2020, Chinese President Xi highlighted that Covid-19 had “sounded the alarm” on food waste, later launching the “Clean Plate Campaign” to try to prevent food waste.

Singaporean defence analyst Andy Wong told the Globe he believed China was looking to increase its grip on the South China Sea due to this food insecurity back home.

“If China has a problem feeding them from the land then they’re going to turn increasingly to the sea,” Wong said. “[China would take] every single bit of coastal territory and disputed territorial waters in the South China Sea that they can get their hands on, so as to stake claim as to whatever resources they can get.”

China has some of the most complex and difficult capture fisheries management in the world. But, current capture fisheries management is looking more at the long game, focusing on the intensification of resource conservation and ecological restoration. These efforts will see a slower growth in aquaculture, marine catch and freshwater catch compared to previous decades.

Data from the commercial fishing transparency group Global Fishing Watch also showed a whopping 18.4% decline in active Chinese fishing vessels and 10.7% fewer fishing hours in 2020 compared to 2018-2019.

But an apparently shrinking fishing industry hasn’t affected the view from the dinner plate, with the demand for fish still rising. Consumers there are eating more seafood than ever before, making for 21% of animal protein consumed in China compared to a global average of 16%. Government surveys of household consumption have shown a rise in national per capita consumption of seafood from 3.1 kg in 1985, to 11.4 kg in 2016. That figure doesn’t include out-of-home consumption, which could add an extra 35%.

Hongzhou Zhang is a research fellow at Nanyang Technological University who has made a career out of researching and writing about China’s food security, as well as fishing policies and the South China Sea. He explained to the Globe that there is a disconnect between China’s slowing marine and freshwater catch and the rising demand for fish by Chinese consumers.

“That means that China will either have to import more from the international market, or that Chinese consumers will be forced to consume less [fish], like the case of pork,” said Zhang. “I would say that that is the overall picture, something quite worrying in terms of meat supply, for pork, beef and fishery products.”

Tabitha Grace Mallory, founder and CEO of the China Ocean Institute and an affiliate professor at the University of Washington, explained that China is turning increasingly to imports from foreign countries to feed hungry mouths back home.

This all comes down to China’s growing middle class, who want the kind of higher-price-point seafood found more commonly in foreign waters. That includes more basic fare such as hair tail, squid and croaker, as well as higher-dollar varieties like crabs, lobster and salmon.

“That’s a bit different from a food security issue. People aren’t on the brink of starvation,” Mallory told the Globe. “In the past, people in China would eat very low quality, low-value seafood. Now, consumption patterns have changed.”

Even if food security isn’t a top factor in China’s push to the sea, access to the fishery may be appealing for economic reasons.

Some observers argue China’s long-term interest could be to place itself as the central power in a fishing industry that would ultimately sell fish back to other, displaced claimants of the sea. As China’s maturing economy offers easier work options to fishermen who prefer dry land, Zhang told the Globe a future, Chinese-led industry could include many more crewmen from Southeast Asian nations. Fishermen from the other seafaring nations could end up back on the waters they once sailed, serving on Chinese vessels in contested areas held more securely under Chinese authority.

According to his research, this has led to a rise in labourers from Southeast Asian nations, like Vietnam and the Philippines, appearing on Chinese fishing vessels.

“Local [Chinese] fishers go out for a few years to sea, then they open shops, and they stop wanting to go out,” Zhang said. Over the years, he’s made many trips to fishing villages throughout China, speaking to fishermen to better understand their changing lives.

“Now [Chinese] labourers can find better opportunities without having to join the fisheries sectors, so now that’s why you see an increase in labourers from Southeast Asian nations, like Vietnam and the Philippines, starting to appear on the Chinese fishing vessels.”

Zhang believes that this trend will only continue, and also believes that the South China Sea could become a marketplace of fishermen trading fish stock. He said that this is already an area Chinese scholars are pushing for, to promote fishery trade among the claimant states.

China can make some gains in the South China Sea without any interference from the outside. This has been shown across the board. It’s the same as their attitude towards Taiwan and Hong Kong

But signs of cooperation are hard to come by right now.

The past year has seen China push limits in the contested waters, creating new paramilitary and political-legal actions in the South China Sea, establishing two new administrative districts and enforcing them with naval forces. Fearful of what this would mean for their own access to the waters, the US pushed back against these claims, announcing a “strengthening” of US policy regarding China’s claims in the sea.

Mallory suggests that the recent rise in aggression from China in the South China Sea could be linked to a global preoccupation with the Covid-19 pandemic, with China making the most of having less international attention on the issue.

“China can make some gains in the South China Sea without any interference from the outside,” said Mallory. “This has been shown across the board. It’s the same as their attitude towards Taiwan and Hong Kong.”

For Zhang, it’s impossible to explain the Chinese strategy in the disputed sea through just one lens, whether that be food security, resource control or geopolitical opportunism.

“The entire situation of the fishing issue is much more complicated than a single narrative,” he said. “[But] China will still have to catch fish. Whether they like it or not.