The women are working for free tonight, managing a small Phnom Penh bar set up like a cooler with a backroom.

It’s a good deal all-around. The bar’s owner earns profits off the drinks, a cut of which goes as commission to the young women giggling and teasing each other on the red plastic seats at the hole-in-the-wall pub in the city’s Golden Sorya Mall near the riverside. Besides their cut of the beverage sales, there’s more lucrative work to be done with the clientele – some of whom can become boyfriends, as long as they come with enough charm and cash.

On a recent weeknight, a few men stopped by, some of whom wandered with the girls to an unseen upstairs. Otherwise, the mall was quiet, most of its businesses closed thanks to Cambodia’s rising Covid-19 outbreak.

“Better to be here than at home bored,” notes the head hostess, introduced by her friends and co-workers as the “lady boss”. Nowadays, some regulars don’t want to come by the bar anymore. In that case, she explained, the women can make a house call.

Most outsiders would consider the side-lines at bars like this to be sex work, but the group doesn’t see it that way – to them, it’s more like entertaining or picking up a boyfriend. While they don’t focus too much on the legalese of their job, lawmakers and non-governmental organisations fill in the blanks.

Illegal on paper, yet common in reality, prostitution is one of Cambodia’s best-established but not formally recognised industries. Vague laws that conflate sex work and trafficking leaves those voluntarily in the industry defined as anything from criminals to victims, as they’re subject to police harassment, raids, and forceful assumptions about why they’re there.

Despite its prevalence, sex work is often so taboo that authorities, sex workers, and non-governmental organisations struggle to even discuss it in the same terms.

“A lot of local authorities still do not know what [sex work should be] called – human trafficking, sexual exploitation, sex work, prostitution, soliciting, or procuring prostitution,” said Eng Chandy, the advocacy and networking programme manager at the Gender and Development Center (GADC), which advocates for gender sensitive projects, national laws and policies in Cambodia.

“But, in all cases, police would fine or collect individual sex workers’ money or bring them to education centre.”

The life of a sex worker operates in a legal grey area in Cambodia, making it all the more difficult for people like Sok Linda, who has worked in the sex industry for eight years and is also an Organising Officer for the Women’s Network for Unity (WNU), an advocacy group for sex workers in Cambodia founded in 2002.

‘Freelance’ sex workers, or those who work on the street, face the brunt of arrests, bribes, and violence. But despite Linda’s less tenuous job at a KTV, or a karaoke parlour, she still says sex workers are treated like criminals.

“The implementation of the law has arrested sex workers more than traffickers,” Linda said, who believes security and police alike take advantage of it.

Covid-19 restrictions have shuttered most of the usual spots in which women such as Linda have made both their livelihoods. Karaoke parlours have been among the first businesses closed by authorities in each of Cambodia’s viral outbreaks of the past year, and today, most of the capital’s red-light districts have been forced into hibernation.

On a recent night in the riverside area, a usually tourist-friendly promenade adjacent to side streets of gaudily lit hostess bars, only a few women were left to roam the avenues looking for clients. Some women gathered to share a quiet meal in front of their darkened workplaces, mostly small beer rooms with dim windows and names like the Honey Pot Bar, slotted against each other in dense rows.

What little action remained on the street was likely to be dampened even further as authorities announced the next day, on March 31, a nighttime curfew to stem the rising Covid-19 infection counts. With an 8pm cutoff, there’s little time for nightlife during an outbreak.

Linda says that during Cambodia’s second Covid-19 mini-wave late last year, police raided a karaoke bar she used to work at, demanding bribes, seizing property, and arresting sex workers. But while these raids were justified in the name of Covid-19, raids like this aren’t new to Linda and her coworkers. Legal ambiguity has long left them vulnerable to demands at the whim of police. Oftentimes, Linda explained, raids from law enforcement end in bribes of money, property or sex.

“If they want to get back their motorbike, they have to pay $500 per moto. If not, just sleep with the police for one night,” she said.

Those without a fixed workplace are also vulnerable, says Pech Polet, the director of WNU. Polet said while police conduct the raids, security guards for different businesses report women waiting for clients around Wat Phnom, a common spot for sex workers, who are expected to pay them a bribe of $3.50 so their work isn’t disrupted.

“The reason the security guards arrest sex workers is because of the social order [law] or to rescue sex worker, but this is not really rescuing them,” Polet said.

Not having money for a bribe often comes at a higher price.

“Sex workers are still routinely arrested by police for allegedly causing public disorder and sent to the Prey Speu centre, where they are imprisoned without criminal charges for up to six months,” Chandy said. The Prey Speu centre is also used to detain drug users and the homeless, who have poor access to rehabilitative opportunities and medical care.

It’s widely believed that sex work is illegal in Cambodia, but this confusion is compounded by unclear and broad definitions. One of the laws that facilitates harassment of sex workers is the 2008 Law on the Suppression of Human Trafficking and Commercial Sexual Exploitation – which broadly prohibits procuring prostitution and soliciting for prostitution in two of its articles. Breaking this law results in one to six days imprisonment and a fine of up to $2.50.

“Since the law is lacking of explanation, police and authorities would threaten sex workers and punish them or fine them and believe that they are doing something against the law,” said Chandy.

“[But] the law does not really mention punishing individual prostitution, but procuring prostitution or providing places for prostitution acts. Does this mean that individual sex worker who would volunteer being a sex worker without third person getting benefits from her or him is okay by this law?”

A lack of clarification between procuring prostitution and soliciting, bribes that grease the industry’s proverbial palms, and the umbrella term of trafficking means the practice continues with murky regulation. This causes big problems for the Kingdom’s sex workers, especially when the law sets the standard for non-governmental organisations working there.

Michael Brosowski, founder of anti-trafficking organisation Blue Dragon in Vietnam, says it’s extremely important these definitions are clear. He told the Globe that he’s aware of foreign organisations operating under their own moral understanding of sex work. In the case of Cambodia, this means using the country’s legal grey area over the industry to meet their institutional goals.

“NGOs do tend to play a bit fast and loose with definitions and every organisation may have its own definition, which can be unhelpful,” Brosowski said. “NGOs often know that if they talk about trafficking, that will get the attention of people.”

For organisations with funding that depends on winning the interest of donors, attracting the kind of attention that comes with anti-trafficking programmes, as opposed to sex work, can be an important task. But this approach can lead to a dangerous conflation of the two.

LICADHO, a Cambodia-based human rights organisation that monitors state violations as well as women and children’s rights, cautions against automatically grouping together sex work and trafficking. The organisation says helping people in either category requires an understanding of the differences between them.

“If a person has consented to sex work by their own free choice, that is not human trafficking,” LICADHO Director Naly Pilorge told the Globe. “Conflating sex work and human trafficking neither improves sex workers’ lives nor contributes to [eliminating] human trafficking. Instead, doing so can undermine sex workers’ rights.”

Not only can these unclear definitions impact sex workers, they can also make it harder for survivors of trafficking to get the help they need in court if the wording of the law is vague.

“When cases get to court or when the government is determining assistance for survivors, those definitions [between trafficking and sex work] are everything,” said Brosowski. “[But] they’re not the sort of sexy thing that runs in the headlines or that NGOs would talk about on social media.”

In Cambodia, Article 298 of the Criminal Code prohibits soliciting in public places, while the infamous draft Law on Public Order, proposed in 2020, would prevent women from wearing “items that are too short or too revealing”, among provisions that could effectively criminalise almost any activity conducted in a public place.

But Linda believes the traditional mentality about gender, as outlined in the public order law, doesn’t do sex workers any favours.

“Some people and other NGOs are still adhering to the caricature and stereotype of [sex workers], especially adopting the patriarchal idea or system that means women can’t have many partners,” Linda said. “This leads to the discrimination againt sex workers and leads to exploitation, abuse, violation and detention.”

When it comes to the state drafting these policies, it’s clear what trafficking and sex work do have in common – they involve women and sex, both subjects on which Cambodian authorities have no shortage of opinions. Polet saw the country’s modern laws as an outgrowth of traditional gender roles, especially those that prescribe proper behaviour for women.

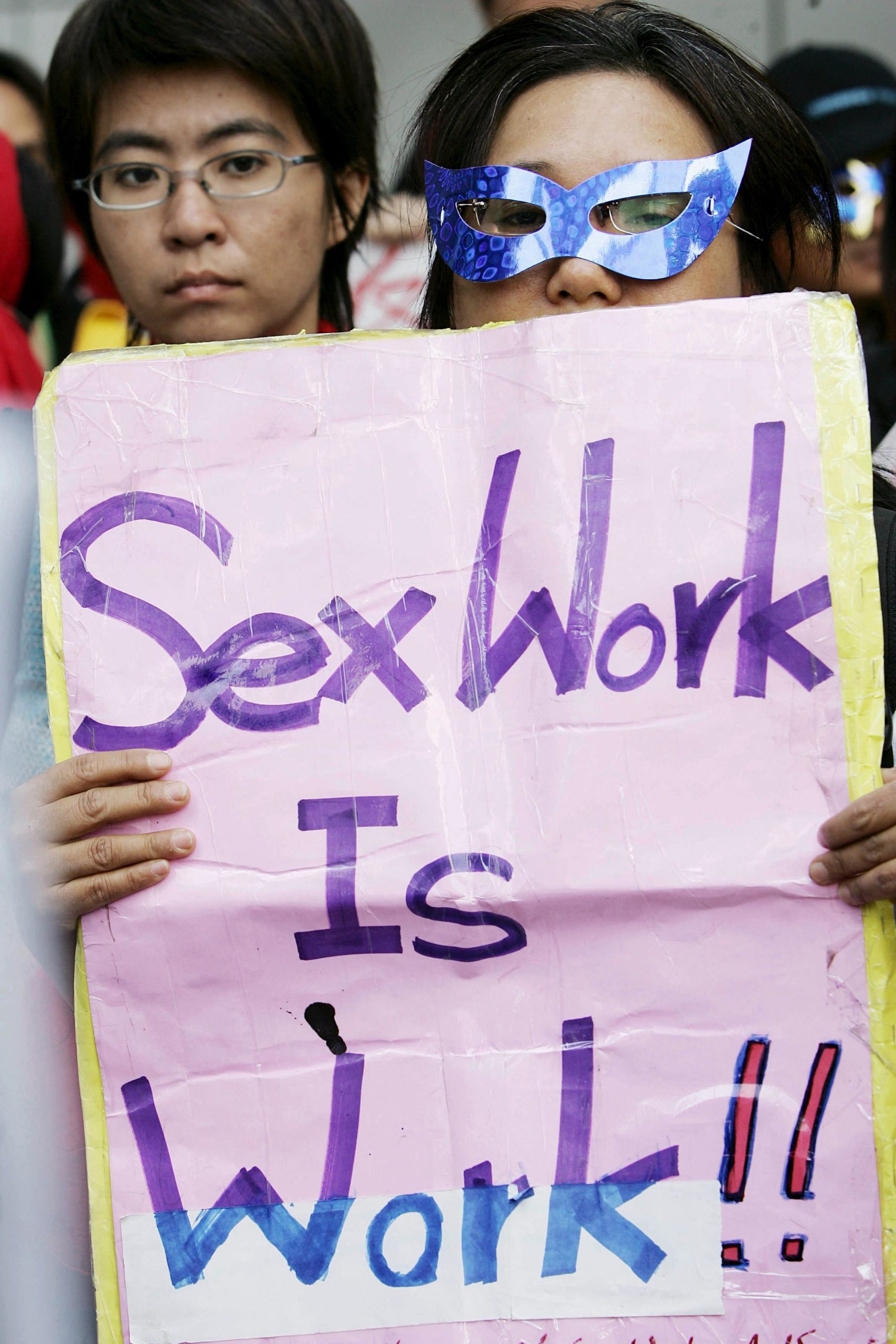

“It is deeply rooted in our country, which has not allowed, especially women, to choose their profession or work by themselves,” Polet said. Her organisation, the WNU, is working towards decriminalising sex work in the Kingdom and plans to become a full-fledged union.

She added laws governing sex work tend to prevent real conversations about women who want to be in this industry, especially during meetings with authorities. She says her attempts are usually thwarted by officials steering the conversation to trafficking or child exploitation.

“They said the only way they can protect the people from trafficking is not allowing to have sex work in our country,” Polet said, referencing her 5,000-member-strong organisation’s dialogue with the Ministry of Interior, which oversees the National Committee for Counter Trafficking, at the 2018 National Forum.

Polet explained these broad strokes did not address the reality of the people she represents.

“Very few of our members mentioned they’d been trafficked before,” she said.

A lack of hard data is key to the argument. Most are quick to admit the actual amount of sex trafficking in Cambodia is an area few have done in-depth research on, but conversations are usually propped up on anecdotal experiences.

A major player in the game is Agape International Missions (AIM), a faith-based NGO that has made international headlines with their SWAT-style raids. They use the Global Slavery Index as their metric of sex trafficked women in Cambodia – an all-encompassing figure which states 261,000 people are living in modern slavery in the Kingdom.

AIM cites the US Department of Justice and the Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000’s definition of sex trafficking, which regards victims as someone who has been recruited, harboured, or obtained for the purpose of commercial sex. The organisation’s latest human trafficking raids were in January, but they were unable to comment on how they identify victims.

“We focus on raids that involve minors but will do cases just with adults if we receive information they’ve been trafficked and need help. Adults that are part of a raid are interviewed by police and offered aftercare services by Dosvy but it’s up to them whether they accept this or not,” said Kevin Holst, AIM vice president of advancement, in an email statement to the Globe. He added they work with Cambodian law enforcement, including the Cambodian Anti-Trafficking and Juvenile Protection Police to conduct raids on brothels that are selling minors for sex

Raids on brothels and karaoke bars have been the subject of criticism in recent years. Those conducted by Cambodian police have resulted in the death of at least one sex worker in 2017, and those of non-profits, which while receive support in home countries, have been publicly questioned by other NGOs, researchers, and media alike on their truthfulness for whether survivors from their raids were necessarily trafficked women.

It was a bit challenging to be able to continue operating in the way they did, the ones I know of very well were involved in sort of more of the forced rescues

Ruth Elliot, a British psychologist who started Daughters of Cambodia, a faith-based nonprofit, in 2007, describes her organisation’s method as softer in approach to raids, based on handing out cards in places where sex is sold. She credits this lighter approach as a reason they’ve been able to stay open while other NGOs have left the anti-trafficking industry.

“Some of them, it was a bit challenging to be able to continue operating in the way they did, the ones I know of very well were involved in sort of more of the forced rescues,” Elliot said. “Sometimes a model needs to change, it’s true. We need to be able to be flexible, to be able to adapt to a situation.”

Most organisations have a firm operating definition of what trafficking is, including Daughters of Cambodia and AIM, but exploitation is another broadly defined word that has little standardisation in the industry, defined as anything from a third party profiting from trafficking, to how an organisation feels about the nature of sex work.

“From our perspective, we believe that doing sex work is pretty much an exploitative situation for them,” said Elliot.

Based on conversations with women who have gone through her programme, Elliot believes about 30% have been trafficked and about 70% are in the sex industry for their own financial reasons.

“I am not someone who judges people, and our organisation doesn’t judge, we prefer to love people and be kind and offer them a way out of the suffering they have been experiencing as sex workers.”

While few would question the good intentions of these NGOs, women’s advocacy organisations in Cambodia say that assumptions about the morality or the validity of sex work can negatively influence formal definitions.

Bunn Rachana, executive director of Klahaan, a campaign-building women’s advocacy group, says her organisation often hears assumptions that women who are sex workers must have been trafficked or forced into the industry.

But she told the Globe that there are multiple reasons why women join the industry, prominent among them financial considerations.

“Certainly, for some, such reasons can include severe economic hardship – just as is the case for those who work in other sectors of the Cambodian informal economy, such as trash pickers, who might ideally prefer less precarious work,” Rachana said.

“But to say that ‘all sex workers have been trafficked’, only serves to invisibilise these women’s own agency and autonomy, and creates further stigma.”

Still, the problems of unregulated and sometimes violent law enforcement, which only exacerbates danger for sex workers, begin with the state’s refusal to make the difference between the trafficking and sex work clear.

This increased safety in legal clarity and standardisation across the nonprofit sector is something advocates say would come with more and better regulation of the industry, rather than lumping all sex work under the umbrella of trafficking.

“The system is exploiting them if they don’t know what their right is,” Polet said. “The only sustainable thing we can provide them [with] is let them know their rights.”