Christmas has just passed, and while Steven Mnuchin may not look much like Santa, he certainly has a naughty list that Cambodians Oknha Try Pheap and General Kun Kim found their way onto on 9 December.

Like Santa, Mnuchin knows if you’ve been good or bad, but unlike Santa, Mnuchin is the 77th US Secretary of the Treasury – and if he thinks you’ve been naughty then you’ll get more than just coal in your proverbial stockings.

This year both Oknha Try and General Kim made it onto Mnuchin’s exclusive list – the Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List (SDN), run by the US Department of Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) – which targets a broad group of reprobates ranging from human rights abusers to corrupt officials, money launderers and financiers of terrorism.

The addition of both men was authorised under the 2012 Magnitsky Act – introduced by Obama and strengthened through President Trump’s executive order 13818 – allowing OFAC to effectively cut them out of the international banking system.

For Oknha Try and General Kim though, their names were added to this infamous list on a most conspicuous day, with 9 December being International Anti-Corruption Day.

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced on that day that 68 individuals from nine countries had been sanctioned under the Act. These included individuals from Cambodia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Latvia, Libya, Myanmar, Pakistan, Serbia and South Sudan. Pompeo was keen to remind US companies that anyone found to be interacting with Oknha Try, General Kim or any of the other 66 individuals would expose themselves to sanctions of their own.

Ostensibly, the sanctions don’t sound so harsh; a travel ban to the US and a freezing of assets held stateside. But as the two men are perhaps now realising, the wider implications are dire.

“It’s already pretty much a financial death sentence. They cannot do banking or receive payments in dollars in the form of wires, cheques or credit cards. Forget it. They can only operate in cash and who does that?” says Sophal Ear, an associate professor of diplomacy and world affairs at Occidental College in California.

“Not banking is kind of hard. Anyone named becomes kryptonite, or untouchable anywhere they go. Any American dollars that go to these individuals could be frozen … Without these [sanctions] you might as well give Phnom Penh a hug,” he adds.

Ear, whose father died as his family fled Cambodia in 1976, has long been an outspoken critic of the Hun Sen administration and sees these sanctions as a step in the right direction.

“It sends a message: we’re watching you, Phnom Penh. You can’t just get away with whatever you want. There’s a price to pay,” he says.

Anthony Galliano, chief executive officer of Cambodian Investment Management Holdings, explained the far-reaching and crippling nature of the sanctions.

“The named individuals are prohibited from entrance to the US and use of the US banking system, additionally any of their assets held by American financial institutions or their transactions are frozen,” he explains.

“The Magnitsky law has far-reaching consequences beyond the US border … The real impact of the sanctions is the signal, the overwhelming majority of the international banking system generally follows, given the absolute necessity of having unfettered access to the US payments and banking system.”

The men behind the sanctions

Oknha Try is, as the title suggests, a tycoon, but one who made his money in the timber industry. Try Pheap Group Co., Ltd. was officially registered with the Ministry of Commerce in 2003 and has since expanded its operations from logging to tourism, hotels, handicrafts, petroleum, agro-industrial crops, dry ports and special economic zones.

The group’s website depicts a jovial Try, smiling for the camera above his message as director-general of the company, in which he lays out his eponymous plan “the Strategic Development Plan, Vision: Try Pheap = Everlasting Development 2015-2020” as a roadmap for success.

A 12-storey condominium building in Phnom Penh’s pricey BKK1 area, three integrated casino resorts in Pursat, Ratanakiri and Preah Vihear, as well as two dry ports in Ratanakiri and Kampong Speu, the Try Pheap Ou Ya Dav Special Economic Zone in Ratanakiri Province and a second SEZ in Pursat province and, of course, PAPA Petroleum – all of this is owned by just one of the 11 companies controlled by Oknha Try, and all now face sanctions by the US Treasury.

While estimates on his wealth are hard to come by, OFAC’s assessment that Oknha Try’s riches may be ill-gotten is what earned him a place on the SDN List.

“Pheap has used his vast network inside Cambodia to build a large scale illegal logging consortium that relies on the collusion of Cambodian officials, to include purchasing protection from the government, including military protection, for the movement of his illegal products,” the treasury department said in a press release.

Oknha Try Pheap has connections at the highest levels of government and sits at the helm of an illegal logging network that relies on collusion with state officials and enforcement agencies to fell rare trees, traffic logs across the country and load them onto boats bound for Hong Kong

Global Witness

Illegal logging has long blighted Cambodia, but it was Global Witness – a British NGO that shines a light on the exploitation of natural resources – who first raised the alarm on Oknha Try in 2015.

“Cambodian tycoon Oknha Try Pheap has connections at the highest levels of government and sits at the helm of an illegal logging network that relies on collusion with state officials and enforcement agencies to fell rare trees, traffic logs across the country and load them onto boats bound for Hong Kong. This black market trade is destroying the livelihoods of indigenous and forest-dependent communities,” they wrote in February 2015.

The Global Witness report added that environmental activist and forest crime investigator, Chut Wutty, was shot dead in 2012 while escorting journalists from The Cambodia Daily into the illegally deforested area. They also cited the case of Hang Sorei Oudom – a journalist who had covered Oknha Try’s alleged links to illegal logging – who was found dead in the boot of his own car.

No representative of Try Pheap Group Co., Ltd could be reached for comment by Southeast Asia Globe regarding the sanctions.

The second Cambodian facing Magnitsky sanctions is one General Kim – who was Chief of Joint Staff in the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces until 2018, but these days holds an impressive rank as National Committee Disaster Management First Vice-President.

OFAC’s statement, however, paints a different picture of the man.

“Kim … was instrumental in a development in Koh Kong province and had reaped significant financial benefit from his relationships with a People’s Republic of China (PRC) state-owned entity. Kim used RCAF soldiers to intimidate, demolish and clear-out land sought by the PRC-owned entity. Kun Kim was replaced as RCAF Chief of Staff because Kim had not shared profits from his unlawful businesses with senior Cambodian government officials,” claims OFAC, who also designated three of Kim’s family members for their involvement – King Chandy, Kim Sophary and Kim Phara.

Like many senior Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) officials, General Kim is ex-Khmer Rouge with a long and murky history. According to Human Rights Watch – who in June 2018 released a 213-page report entitled Cambodia’s Dirty Dozen: A Long History of Rights Abuses by Hun Sen’s Generals – he is “a notorious human rights abuser”.

The report points to his involvement in violent political suppression, intimidation and illegal logging across the country – even pointing to a 1996 report from the UN that refers to General Kim as Hun Sen’s “chief hatchet man”.

When contacted by Southeast Asia Globe for comment on the sanctions, General Kim refused to answer questions put to him and deferred to the official statement released by Cambodia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation (MOFAIC).

Culture of impunity

All of this has occurred in a Kingdom routinely highlighted by innumerate global organisations as one of the most corrupt countries on the planet.

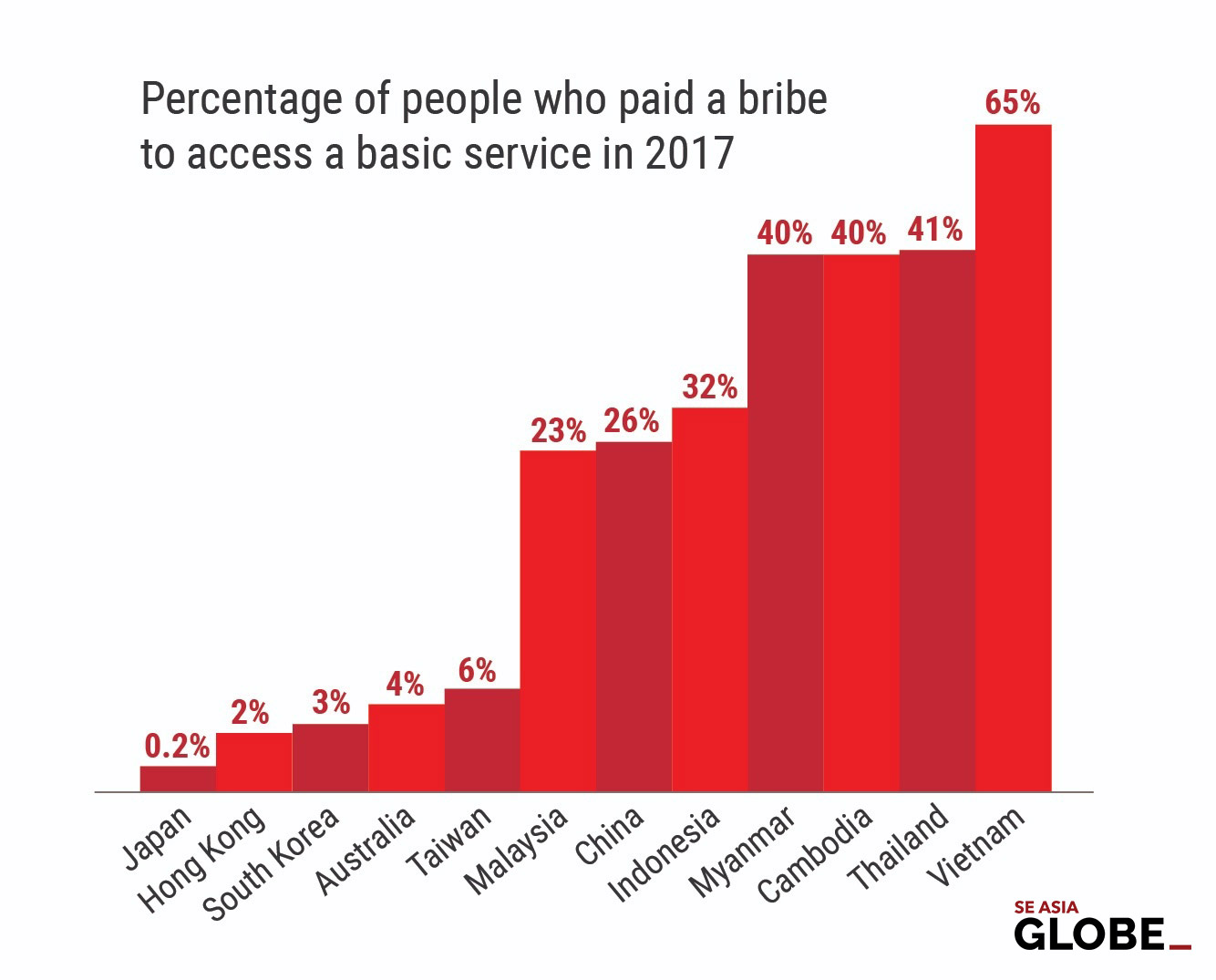

In 2016, TRACE International – a bribery-focused NGO that works globally – claimed Cambodia was the fifth most at risk country in the world when it came to bribery in business.

As of 2019, Cambodia hadn’t changed much. Out of 51 Asian nations studied, TRACE ranked Cambodia as 48th – making it more corrupt than neighbours Laos PDR, Vietnam and Thailand, and 189th globally.

In a culture of such impunity, unsurprising then that the sanctions placed on General Kim and Oknha Try are not the first to be applied to Cambodians.

In June 2018, General Hing Bun Heang – head of the Prime Minister Bodyguard Unit – was slapped with sanctions by the US under the Magnitsky Act over his purported involvement in a grenade attack on opposition party members back in 1997. At least 16 people were killed by four grenades that were thrown into a rally in central Phnom Penh and more than 150 people were injured.

In response to the 2018 sanctioning of General Heang, the Ministry of Defence expressed “regret, [and] dismisses and strongly condemns the U.S. Treasury’s rude action”.

This sentiment was echoed, almost word for word, in a statement from the MOFAIC in response to General Kim and Oknha Try’s sanctioning, expressing their “strong dismay over the arbitrary designation of Cambodian officials”, also referring to the US’ accusations as “disturbing” and “groundless”.

MOFAIC spokesman Koung Koy declined to comment.

Harming the wrong people?

While Magnitsky sanctions come in from the US, a final decision from the EU is expected regarding the highly-debated Everything But Arms (EBA) preferential trade status that Cambodia currently enjoys.

EBA currently guarantees tariff-free exports of Cambodian goods to the EU – the world’s largest trading bloc – and in 2018, exports from the Kingdom to the EU were valued at $5.8 billion. Losing the preferential trading status could cost Cambodia $654 million a year.

There has been much chatter among the garment and footwear manufacturing sector – which currently employs around 800,000 people in the Kingdom – as it stands to be hit hardest by the potential loss of EBA. The EU’s final decision is expected on 12 February and could see EBA revoked by August 2020.

The EU’s decision to review Cambodia’s EBA status has raised issues regarding human rights, democracy in the Kingdom and the efficacy of blanket trade sanctions when compared with targeted sanctions like those against General Kim and Oknha Try by the US.

“Actually morally speaking this [targeted sanctions] is more appropriate,” argues Lao Mong Hay, executive director of the Khmer Institute for Democracy.

“It is more correct because it’s unethical to punish innocent people such as workers who are used for the export of goods to the European and American markets, that is perhaps fairer than the suspension of the US’s GSP [Generalized System of Preferences trade benefits], from the moral point of view. There are laws punishing those who are known for having destroyed democracy, human rights and the rule of law in Cambodia,” notes Lao, who also suggests that sanctions against financial institutions would prove more effective than targeting individuals.

On this matter, Ear agrees: “Sure, if you follow the narrative, EBA and GSP suspension are bad because they hurt a million women, so what are you left with? Targeted sanctions.”

But there remains much debate over whether or not sanctions are as effective as the West would like to believe. Sanctions have evidently become the preferred means of diplomacy for the Trump administration, but experts argue that they don’t necessarily achieve what they set out to do.

“The point of economic sanctions is to cripple the ‘coercive capacity’ of the abusing state. First, the individuals’ assets being frozen does not necessarily cripple Cambodia. Also Cambodia’s biggest trading partner is the EU, not the United States, so in that sense, it [sanctions] will have some effect but likely not that big,” suggests Robin Michael Garcia, a lecturer in International Relations at the University of Asia and the Pacific.

While the Magnitsky sanctions are thought to be fairly extreme in their impact, Garcia contends that “being ‘cut off from the international financial system’ is a bit exaggerated”. He also argues that sanctions are a delicate affair.

“On the other hand, if the sanctions are directed towards the state and not individuals and it curtails the economic capacity of the citizens, some studies show that human rights abuses might even increase because of the threat of riots and rallies against the state. It’s a balance.”

Cambodia can afford to be hard on America because of China’s support. Perhaps the status of the relationships between Cambodia and America depends on China. Cambodia is gaining a lot from China – the gain is more visible than that from the US’s GSP and the EU’s EBA

Political analyst Lao Mong Hay

Has this sentiment trickled through to Europe? On 9 December, the EU announced they would be breaking ground on their own Magnitsky-esque law.

“We have agreed to launch the preparatory work for a global sanctions regime to address serious human rights violations, which will be the European Union equivalent of the so-called Magnitsky Act of the United States,” said EU chief diplomat Josep Borrell.

All of this then begs the question – where now for Cambodia? As relations with Western powers deteriorate, many analysts point to China as the only logical conclusion.

Whether targeted sanctions will prove effective remains to be seen, but there’s a very real threat that they could push Cambodia further from the democratic values such sanctions are intended to instil, and towards more authoritarian governments.

“It is truer to say that Cambodia can afford to be hard on America because of China’s support. Perhaps the status of the relationships between Cambodia and America depends on China. Cambodia is gaining a lot from China – the gain from China is more visible than that from the US’s GSP and the EU’s EBA,” reflects Lao.

Garcia agrees, claiming that China is definitely the winner in this flurry of sanctions.

“We already see Cambodia [moving] in China’s direction for a long time, ASEAN is the loser. CMLV [Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam] countries are moving closer towards China, while others to the West,” he says.

However, Ear points out that for Oknha Try and General Kim, the ever-more entwined relationship of Cambodia and China may be of little use in improving their personal fortunes.

“Unless they plan to keep all their assets in Yuan/RMB, they really will be affected. It’s not easy banking with China. China has capital controls.”