The group of skinheads surges forwards. On the stage in front of them the band is dressed in boots, collared shirts and red braces. As the opening chords of another street-punk anthem screech from the soundsystem, the Malay singer clasps the mike and offers a rugged preface to the song. “This one is against all racism and discrimination in our country… Do you have a problem with race? If you do, we’ll crush you to pieces.”

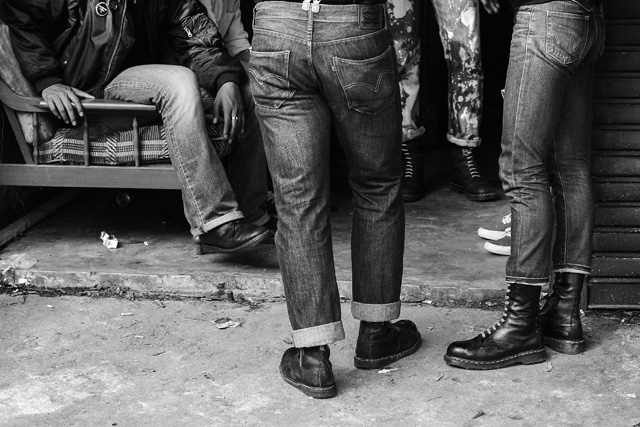

The crowd is a melee of young Malay men mostly clad in Lonsdale shirts and Doc Martens boots – the unofficial uniform of skinheads the world over. Deep cheers and pumped fists fill the air, then comes pogoing, sweat and sing-along hymns of grassroots revolution.

Skinhead culture emerged in the 1960s in Britain, largely arranged around fashion and music. The shaven heads and shirts were aggressive by design and also reflected the scene’s working class roots. Music was equally crucial, and the skinheads’ love of reggae meant that their identity was intrinsically linked to black immigrants and culture. The scene died out by the early 1970s, only to be reborn again later in the same decade. However, according to Timothy S. Brown, writing in the Journal of Social History, the second wave of skinheads was more susceptible to corruption by the right-wing rhetoric of the time.

“Economic decline, scarcity of jobs and increased immigration intensified latent racist and right-wing attitudes in British society during the 1970s and 1980s, and the skinheads reflected these prejudices in exaggerated form,” wrote Brown in his article titled “Subcultures, Pop Music and Politics: Skinheads and ‘Nazi Rock’ in England and Germany”. “With their reputation for violence and patriotic-nationalist views, skinheads were seen as a particularly attractive target for recruitment by the radical right.”

Even though right-wing skinheads probably never made up a majority, according to Brown, the links between skinheads and fascism had been established. They have been resolute ever since.

With names such as Street Rebel, Chaos Bomb and Oi! Koholik, the majority of Malaysia’s skinhead bands espouses the proletarian masculinity of the original skinheads while staunchly rejecting the racist overtones that emerged later. Such voices are becoming increasingly poignant in Malaysia, a pluralistic society operating under a government that has been criticised for its increasingly Islamist tendencies and that introduced its New Economic Policy in 1971 that has privileged ethnic Malays over Chinese and Indians ever since.

“Being a skinhead in Malaysia means embracing positive, anti-racist ideas of sociopolitical change to challenge our racist government,” says Rozaimin Elias, 34, one of Penang’s leading anti-fascist skinheads and bassist in Kuala Lumpur-based band Street Boundaries. Given his involvement with the opposition DAP party in Penang, Elias doesn’t limit his views to idle music-scene chatter either.

The Malaysian skinhead movement emerged in the late 1980s out of Kuala Lumpur’s early punk and metal scenes and expanded to the rest of the country throughout the 1990s. Elias remembers an unfortunate consequence of the confusion experienced by early Malaysian skinheads: “We wore swastikas because we thought they were cool,” he says. “We had all seen pictures of Sid Vicious wearing the swastika, and we thought it was punk. We just wanted to look different from other Malaysians.”

Brown says that such confusion is quite normal. “Since Malaysian punks were adopting the swastika before they knew what it meant, because it seemed ‘punk’, there is a bit of uninformed copycatting going on – but this is typical of the global spread of youth subcultures. Young people copy style and iconography, but they also infuse these with meanings that are specific to their own situation,” he told Southeast Asia Globe via email.

It was early bands such as ACAB (All Cops Are Bastards) from Kuala Lumpur that led the way and consolidated an active anti-fascist skinhead movement that followed the principles of Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice (Sharp), the anti-racist movement born in New York City in 1987.

“As elsewhere in Southeast Asia, there are progressive Malaysian skinheads … who are not only seen as anti-establishment and engrossed in their subcultural lifestyles, but are also making explicit commentaries about the state of inter-ethnic relations in the country,” said Yeoh Seng Guan, an anthropologist based at Kuala Lumpur’s Monash University Malaysia.

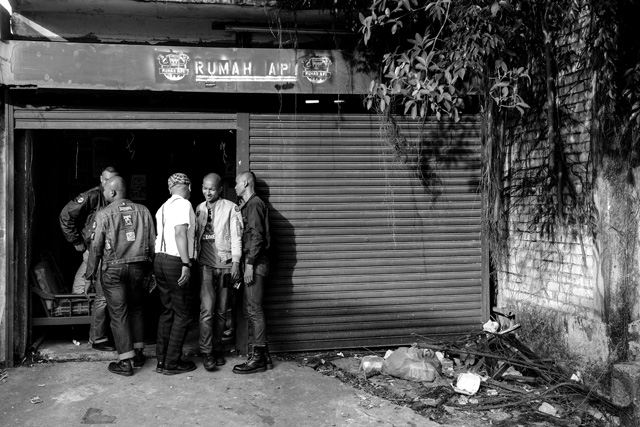

Man Beranak is one of the main faces in the Malaysian music scene. A resident of Rumah Api (The Fire House), Kuala Lumpur’s self-proclaimed “punk space run by punks”, he says that skinheads are always welcome at the venue. “We support them because the underground scene here is very small,” says the 35-year-old. “Although not a skinhead myself, I totally support their anti-racist ideology, and most of these guys are my close friends. We help them voice their dissent.”

The internet has played a big part in Malaysian Sharp skinheads reaching outside of the country. I meet one of Malaysia’s most well-travelled skinheads in Subang Jaya, a southern district of greater Kuala Lumpur. Wrapped into his Lonsdale jacket, tight jeans and coloured leather boots, GG looks hardened by his years in the scene, though he remembers fondly his trip to Europe to connect with the famous anti-fascist skinheads of St. Pauli, an area of Hamburg, Germany.

“They didn’t receive the news of a Malaysian neo-Nazi skinhead movement, as published by Vice, very well though,” recalls GG. “I was so ashamed… I assured them that ours is just a small problem.”

Indeed, a May 2013 story in Vice magazine opened with a photo of 14 Malay teenagers, most of them with their right arms raised in the Nazi salute. The story unveiled the existence of Malay fascist skinheads who wear swastikas, listen to Nazi rock bands such as Angry Aryan and Skrewdriver and discriminate against non-Malays. However, according to Elias, the scale of the problem was somewhat exaggerated in the article.

“A handful of bands such as Brown Attack and Spiderwar define themselves as ‘Malay Power’, but they’re not a real threat. All they do is hang out and occasionally play shows in Kuala Lumpur’s Bukit Bintang area, a place we anti-fascist skinheads go to when our fists get itchy for racists’ jaws,” he says.

“In Germany, neo-Nazi skinheads are a real social threat… [But here] they just loiter wearing swastikas and then go drink beer at Chinese-run food courts because it’s cheaper. Aren’t they supposed to boycott and fight all non-Malays?” agrees GG, laughing heartily.

Of course, the idea of a group of Asian men espousing Nazism seems misguided at best. Even the Vice story ended with the question: “How do you square being a Nazi with not actually being white?” Yet Brown, who is also a professor of history at Northeastern University in Boston, argues that it might make more sense than we think.

“On one level, Asians who think they are Nazis have obviously lost the plot,” he says. “Yet there is a certain logic, since these kids apparently construe Nazism as a template for racial purity that can be transplanted into their very different context, to serve as some kind of ideological buttress for their nativist xenophobia.”

According to GG, the fascists find it difficult to find acceptance in Kuala Lumpur and beyond. “The bonehead [a term used by anti-fascist skinheads to refer to their racist brethren] bands are forced to play at random places because nobody in the scene wants to deal with them,” he explains. “Sharp skinheads, on the other hand, can easily play all the punk spaces, such as Rumah Api in Kuala Lumpur and Soundmaker in Penang, because of our moral integrity.”

Speaking to numerous Malay Sharp skinheads, this idea seems important. Stretching right back to the 1960s and 1970s skinhead scenes in the UK, the ideas of integrity and authenticity were paramount to the ‘original’ skinheads, who often felt that racists had spectacularly failed to grasp the values and origins of the subculture.

The concept persists among Malaysian Sharp skinheads today. Yet there is also an intimation of wishing that wider Malaysian society understood them a bit better. Unlike most of the stereotypes propagated about them, most Malay Sharp skinheads are, in fact, progressive Muslims.

“Take ten of us,” GG says while a Bengali waiter distributes a round of fruit juices to our table, “only one or two would drink or smoke, and we still pray five times a day. As Malays, that’s our way of life. It has nothing to do with what we think of music. Nor how we use punk rock as a vehicle of social change.”