A specially choreographed fireworks display, the opening of a brand new national gallery and a humongous parade – these are just some of the events scheduled for Singapore’s 50th birthday celebrations, known as SG50. Throw in the SEA Games and the Asean Para Games and it is set to be one stellar year for the city-state.

In addition to these bells-and-whistles events, the government has a host of smaller initiatives up its sleeve, such as doling out commemorative birth certificates for babies born during 2015. These will come with a special medallion, a multi-functional shawl, a baby sling, a set of baby clothes, a diaper bag, a scrapbook for memories, a family photo frame, and – last but not least – a baby book. Singapore is not doing things by halves.

Five decades is not long in the grand scheme of things, but the country has come a long way in that time. Where once there were rickety, cheek-by-jowl buildings in the kampongs, there are now rows of neat public housing blocks and gleaming office complexes; festering swamps have been replaced with efficient stormwater management systems. But the rapid changes of the past 50 years have left many Singaporeans struggling to find an identity for themselves and a place in this globalised world.

Since declaring independence from Malaysia in 1965, the country’s history – as taught in schools, played out in parades and displayed in museums – has been dominated by the narrative of the government, nurtured by the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP), which has been in power since independence. Singaporeans are familiar with the story: Under the PAP and founding father Lee Kuan Yew, the island was transformed from a poor pinprick on the map into the wealthy and much-envied nation it is today.

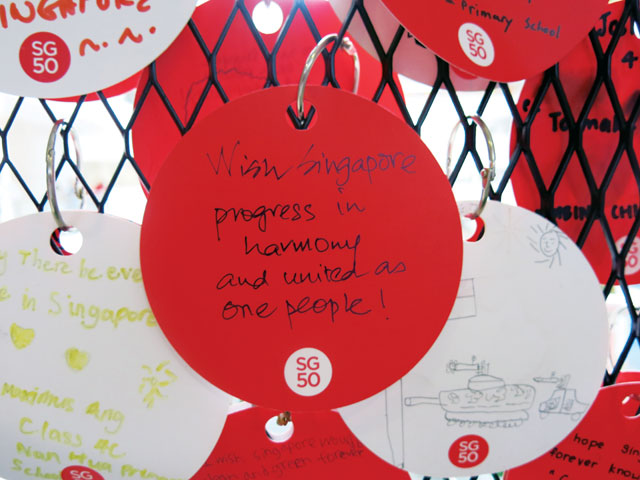

With SG50 though, grassroots efforts to tell Singapore’s story are coming to the fore. Singaporeans are rising to the occasion with their own ways to mark the Golden Jubilee. Lynette Wan and her husband Patrick Shi have received money from the SG50 committee’s Celebration Fund for their project – a book of flash fiction with contributions from senior citizens. “It is my intention that the younger Singaporean readers understand and appreciate the contributions of the pioneers and their can-do attitude that paved the way for our nation’s success today,” Wan said.

“Beyond the events that the government has initiated, Singaporeans are coming forward to celebrate SG50 in their own ways. This shows that Singaporeans not only want to be involved in the celebrations, they also want to own the celebrations by roping in their family and friends and reaching out to a wider community. This will make the SG50 celebrations truly inclusive and meaningful,” said an SG50 committee spokesperson.

The Celebration Fund – with its budget of SGD5m ($4m) – is not the only source of support for ground-up initiatives. Predicting an overwhelming dominance of the state’s narrative, alternative projects have also emerged to ensure a greater range of voices are represented.

Alvin Tan, artistic director of the Necessary Stage, a non-profit theatre company, is a man straddling both sides. Part of the official SG50 committee, he is also in the steering committee of 50/100, a civil society effort to support projects highlighting narratives and stories that are unlikely to make it into the mainstream. Tan recounted an experience he had at an SG50 committee meeting: As the group was discussing the subject of inclusivity, he asked about the inclusion of ‘dissident’ voices such as those of filmmakers who had experienced run-ins with the state. “There was a pause and I felt I must take this pause as a ‘no’,” he said. “Then the meeting went forward to the next thing on the agenda.”

It was this experience that convinced him of the importance of an alternative project such as 50/100. “I think SG50 is doing a fabulous job with recognising ordinary Singaporeans and encouraging active citizenry. That’s why I’m still proud to be associated with it and to be on the panel,” said Tan. “But it’s insufficient. It was then that I felt the need to be on the 50/100 steering committee, to do more for Singapore.”

The tensions surrounding Singapore’s history have been simmering for some time and are expected to gain greater significance during the course of this year. The PAP has held the reins all these years, but challenges have been mounting. Teo Soh Lung, a former lawyer, was arrested during Operation Spectrum in 1987, supposedly as part of a sweep to clamp down on Marxist conspirators who were seeking to overthrow the government. She was detained without trial for more than two years.

Now, Function8 – a group set up by Teo and other former detainees and activists – has its own plans for SG50. It is working on an oral histories project to collect the memories of dissidents, activists and exiles, in the hopes of preserving these perspectives before it is too late. “We felt that there are really so many things that we ourselves do not know,” said Teo. “And all these people, they’re getting old, so very soon they’ll pass on. Then we’ll have zero.”

The struggle for control of the telling of Singapore’s history is perhaps best illustrated by the banning of an award-winning documentary. Despite international acclaim, Singapore’s Media Development Authority refused to classify Tan Pin Pin’s To Singapore, With Love for public screening in the city-state, citing national security reasons. The film profiled several political exiles, some of whom were accused of being communists and had not returned to their home country in more than five decades. “To allow the public screening of a film that obfuscates and whitewashes an armed insurrection by an illegal organisation – and violent and subversive acts directed at Singaporeans – would effectively mean condoning the use of violence and subversion in Singapore, and thus harm our national security,” said the minister for communications and information, Yacob Ibrahim, in response to questions raised in parliament.

The government has also cast an eye back to the years leading up to Singapore’s independence, as a merger between Singapore and the Federation of Malaya was mooted by the PAP and hotly contested by other political parties. The Battle for Merger, a series of radio talks given by Singapore’s first prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, in 1961, was republished in October last year. “As we approach our 50th year of independence, some revisionist writers have attempted to recast the role played by the communists and their supporters on the merger issue,” Deputy Prime Minister Teo Chee Hean said at its launch, adding that the re-publication would give these revisionist views a “reality check”.

“I’m sure there will be lots and lots of literature next year about how great the PAP is,” said Teo Soh Lung with a laugh. “The government has so much money to splurge on their point of view, what the PAP has done… For us to go and contest, compete with them, it’s very tough because we don’t have the financial resources to do that.”

However, interest in debating the mainstream narrative has been growing. Each month, a modest theatre space in central Singapore fills with people attending a Living With Myths panel. Each forum deals with a national “myth”, such as multiculturalism, the vulnerability of being a small island nation, and the linear narrative of history, bringing in experts and academics to discuss each issue. Although it started independently, the series is now one of 50/100’s affiliated projects.

“I think it’s very important to prove that we have a genuine diversity of citizenry, that the narrative isn’t uniform. By showcasing this diversity, it’s renewing people’s faith in Singapore as a whole,” said Choo Zheng Xi, a member of the 50/100 steering committee. “Everything that’s good, everything that’s bad, everything that might not have a place… Through that, people will see that this is something they can be a part of.”

Historian Thum Pingtjin is happy to see this proliferation of voices, stories and perspectives. “[The government] has its narrative and it’s sticking to it,” he said. “But the fact is that these events [the merger and subsequent separation, as well as arrests such as those made during Operation Spectrum] are so recent and need time to play out. In the long run it’s impossible for the government to monopolise or impose its own version of history. There are so many empires or kings or governments that think their version of history or events will last for all of eternity, but they won’t. They never do.”