In April last year, Saza Faradilla sat in an art studio at the Yale National University of Singapore wearing a skirt sewn from printed consent forms. As dusk fell, she set out a box filled with scissors. Beside the box, a sign read “Cut Anything (I’m Wearing)”.

Bound in an intentionally too-tight, bright-red baju karung top meant to highlight her discomfort in her own skin – and bring to mind the richness of blood – Saza sat waiting for her fellow students to pick up the scissors and make a small cut, slicing through the consent forms and cloth of her costume with one sharp motion.

What’s in a Name?

For many Western-based human rights groups, any procedure that involves the laceration or cutting of the female genitals is defined as “mutilation”.

For other activists, however, the term “mutilation” carries too much bias, and they choose to reference the procedure as “female genital cutting”, or “FGC”, instead.

For Southeast Asia Globe, reference to the procedure is best described the by the all-encompassing term “female genital mutilation/cutting”, or “FGM/C”, which has been given to it by UNICEF

“Saya setuju anak saya menjalani sunat perempuan,” each of the forms read in Bahasa Melayu. “I agree with my child undergoing female circumcision.” Saza waited with a plate of nasi campur, offering chip-fulls of meat and rice to each of her prospective cutters and taking the opportunity to talk with them about the persistent practise of female genital mutilation or cutting (FGM/C) among the Malay community in Singapore as they ate.

FGM/C, as defined by UNICEF, is the injury, partial or total removal of the external female genitalia organs for non-medical reasons, and is considered by the United Nations to be a violation of girls’ and women’s rights.

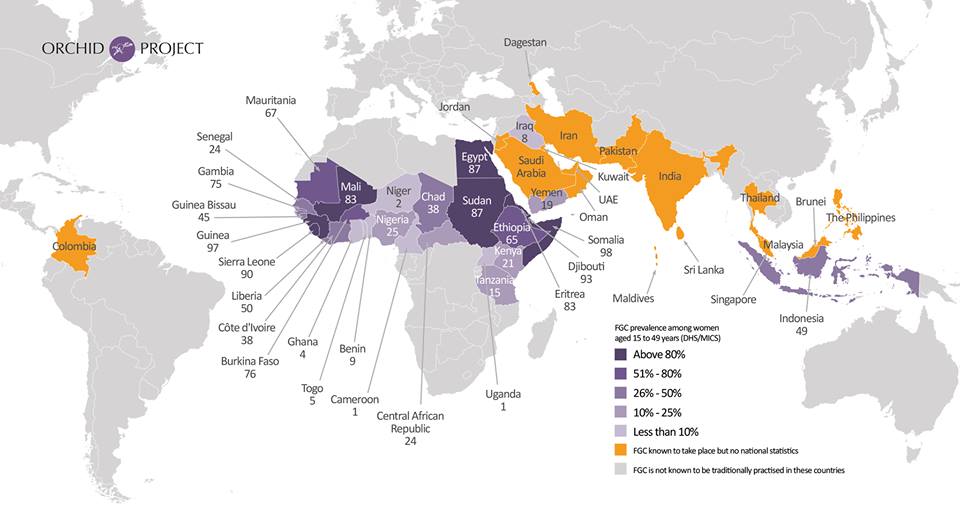

Currently practised in dozens of countries across Africa, the Middle East and Asia, the procedure comes in four different forms, with Types I and IV being the most common in Southeast Asia. Type IV encompasses the pricking, piercing or scraping of the genitalia; Type I, the partial or total removal of the clitoris.

[This was] the sixth class assignment I did on female genital cutting, I think I might be slightly obsessed with the issue.

Saza Faradilla

Better known as sunat perempuan in Singapore, Indonesia and Malaysia, these forms of FGM/C are quietly but persistently practised in the metropolitan city-state of Singapore.

“Singapore is usually presented as a modern, cosmopolitan city,” wrote activist Filzah Sumartono in mid-2016. “Yet, underneath the facade of modernity, female genital cutting…is still practised.”

Her highly personal article, entitled “Speaking out about Female Genital Cutting among Malays in Singapore”, came out at a time when a flurry of western news outlets had begun reporting on the continued prevalence of FGM/C in the country, many demanding some action be taken by the Singaporean government to limit or criminalise the practice.

But Sumartono, project manager for the Association of Women for Action and Research (AWARE), wrote that the government was slow to act, and that few were willing to discuss the practice across the country or within the Malay community itself.

When contacted for comment, AWARE sent the link to Sumartono’s previous work. Despite repeated calls for Singapore’s government to take action against the practice, nothing has changed.

Discussing the cut

Saza now wears her hair at shoulder length, the left side of her head shaven short and often coloured with blonde, blue or purple dyes. Raised in a religious family, she has chosen not to adopt the hijab that her mother wears. Her last name, “bte Zaini” – “daughter of Zaini” – she has abandoned, deeming it too “patriarchal” to carry.

Saza did not know she was among the many Malay women who had been cut until her sophomore year of college. Her younger cousin’s birthday party was packed with partygoers clothed in brightly-coloured jubah, scarves and t-shirts. Saza remembered her cousin was wearing a red-and-blue sailor outfit for the occasion.

A relative approached Saza at the party and told her that her young cousin had recently been “cut”. Confused, Saza asked her what she meant. Her relative responded, “You pun kena sunat” – “You were cut too.”

“My jaw dropped,” Saza told Southeast Asia Globe. “I had never known about this cutting, and I was completely unaware that it was performed on me.”

It was this interaction that encouraged her to launch herself into learning about – and campaigning against – the procedure, which she believes has taken on a slightly more covert and shadowed form in Singapore than it has in other Southeast Asian countries that practise it.

“My complete lack of knowledge until that moment about a practice that my relative described as necessary for women speaks a lot to the specific kind of female genital cutting (FGC) in Singapore: its hiddenness, prevalence amongst the Singaporean Malay community, the debate surrounding the procedure, and reactions to it,” she explained.

My jaw dropped. I had never known about this cutting, and I was completely unaware that it was performed on me.”

Saza Faradilla

For Saza, the years following her discovery have been marked by long talks about the practice with her parents, arranged discussions about FGM/C with members of her school and community, and hours’ worth of intensive research.

“It has been a rollercoaster ride of emotions,” she said.

While FGM/C itself may be little-discussed within families, the internet has provided open sites where anonymous discussion of the practice has become fairly common.

Decorated in pinks and purples, Singapore’s online forums dedicated to motherhood are used by young parents seeking advice from their more experienced counterparts and provide an opportunity for expecting mothers to ask – anonymously – questions they may not be comfortable asking anyone face-to-face.

“My husband is Malay and I am expecting a girl. My husband said he wants our girl to be sunat,” wrote user A_LIM on the family-friendly forum, “Mummy SG”. “What does this involve? And where can I do it?” Respondents came to her aid with dozens of recommendations on doctors, complete with pricing and an expectation of how much bleeding and crying she should expect from her child. Some commenters told her that she might be asked to hold her baby’s legs apart for the procedure.

Many locals who are supporters of FGM/C, including dozens who are active on online forums, view the procedure practised in Singapore as a “small cut” that causes no harm to the child.

“It is NOT genital mutilation. It is ‘a clitoral hood reduction’, and does not do any harm to the female,” said one Singaporean man, responding to an article published by AWARE on Facebook.

“You will ask, why do it?” he continued. “It takes away excessive libido from women; prevents unpleasant odours which result from foul secretions beneath the prepuce; reduces the incidence of urinary tract infections; and reduces the incidence of infections of the reproductive system.”

The belief that FGM/C technically has health benefits has, however, been routinely proven untrue, by medical professionals and human rights organisations around the globe.

Crimes against women

“There is no medical justification for FGM,” reads an official UN statement. “Advocating any form of cutting or harm to the genitals of girls and women, and suggesting that medical personnel should perform it, is unacceptable from a public health and human rights perspective.”

While some may not experience the health consequences of cutting, all types of cutting carry risks, and can often lead to physical and psychological impacts including severe blood loss, scarring, infections, post-traumatic stress disorder and depression, explained a representative for the Orchid Project, a Britain-based charity intent on ending the practice of FGM/C.

“The most important thing to note in the face of arguments that some types of FGC are ‘less harmful’ is that the practice is a human rights issue,” an Orchid Project spokeswoman wrote in an email last week. “FGC is most often carried out to control and suppress female sexuality, and the increasing medicalisation of cutting in countries such as Singapore legitimises a discriminatory practice that both underpins and reinforces gender inequality.”

One organisation striving to address the issue of FGM/C within the Malay community – while simultaneously discussing other topics regarding gender and consent – is called “Crit Talk”, co-founded by activist Nurulsyahirah Taha, better known as Sya.

“At Crit Talk, we address FGC together with male circumcision, in the context of performing medical procedures on children without medical necessity and without informed consent,” Sya explained. “Speaking personally to people, with compassion, definitely helps to change their mind. Our hope is that change happens through our social networks, one person at a time.”

There will definitely be strong resistance from the conservative Muslims as well as the religious leaders within the society,”

Ermawati

“I’m not aware of any other groups locally addressing this,” she added.

For Saza’s older sister Ermawati, the practice of FGM/C had always been on the peripherals of her awareness: she’d known of dozens of young girls in her family, cousins and sisters, who had undergone the procedure. A committed Muslim, she believed it to be mandated by her religion and didn’t question the practice much – until Saza began asking questions about it.

“[FGM/C] was something that was normalised for me,” Erma explained. “It was only when my sister started sharing with me about her research and pointed out to me that the procedure is actually not a must in Islam that I started reading up a bit more about it.”

What she discovered was that the practice was not mentioned at all in the Quran, rarely – and ambiguously – referenced in the hadiths of her religion and that the procedure is far from mandated according to her religion, as she had always believed it was.

“To find out that such a procedure actually is tradition and not really religious did shake me a bit,” she said. “If that is the case, then I don’t think girls should be subjected to it…. No matter how young they are it is still not right, because the reasons for doing it do not make much sense, and I believe that Islam is a religion that is very much tied to logic.”

For Erma, the questions asked by her activist younger sister have helped change her way of thinking – but she doesn’t foresee rapid change on the matter in the coming years without active discussion and the guidance of Singapore’s Muslim authorities.

“There will definitely be strong resistance from the conservative Muslims as well as the religious leaders within the society,” she said. “[FGM/C] exists because long-held traditions and beliefs are hard to change, and I’m sure even if this information were to make its way into the community, it would be met with much disdain or disbelief.”

There is also a lack of awareness among the younger community, she added, who often choose to “go with the flow” of the procedure because they are unaware of the issues surrounding it or fear causing a rift with their elders. Regardless, she said, if she does have any daughters, none of them will be cut.

“If the government were to step in, that would be good, but I doubt that they’ll want to venture into religious territory,” Erma continued. “I feel that if this mandate came from the top religious leaders, though, then the community would be more receptive.”

Through her work meeting with dozens of young Malay Muslims and discussing subjects often defined as “taboo” within the Islamic community, Sya has had firsthand experience learning about the barriers that stand in the way of ending FGM/C – and though she is not an advocate for explicit criminalisation of the practice, she admits the government’s silence is not helping.

“I think a medical ban would certainly help. In Singapore at least, there isn’t much access to traditional midwives who can perform the procedure,” Sya explained. “What might – and I hope will – happen is that parents will consider it too much trouble… and if it’s just… optional, anyway, then it’s not a big deal if not done.”

Barriers to change

While there are no concrete numbers on how many women have been cut in Singapore, it is believed to be highly prevalent among the Malay community, with some estimates based on anecdotal evidence placing the percentage of Singapore’s roughly 200,000 Malay Muslim women who have been cut at upwards of four in five. As activism to end FGM/C has persisted in some form for years, led by organisations like AWARE and young activists like Saza and Sya, though, the government has remained overwhelmingly silent on the issue.

Having refused to provide comment to dozens of media outlets in the past, the Ministry of Health (MOH) in Singapore initially responded to Southeast Asia Globe’s media enquiries with a promise that they would soon “get back” with answers. The questions they were asked were very specific to the government’s role in the continued practice of FGM/C, covering the potential of a law banning or limiting the procedure, the creation of educational programmes on the issue, and whether the ministry would consider maintaining statistics on how often the procedure is performed.

We recognise the practice as a form of violence against girls and women, and as a human rights violation, which means that it is inherently harmful.”

Orchid Project Spokeswoman

Three days later, Winnie Lim – the assistant director of communications at the MOH – forwarded the email, and all of its government-specific questions, straight to the Majlis Ugama Islam Singapura (MUIS), or the Islamic Religious Council of Singapore, which comes under the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth (MCCY). Other officials at the MCCY and at the Ministry of Social and Family Development similarly forwarded all enquiries to the MUIS after originally stating that they would themselves respond.

As an advisory board on Muslim affairs, MUIS does not have the capacity to make laws – but its stance on religious affairs is closely watched and followed by the Malay Muslim community. The MUIS response did not address any of the specific questions enclosed in the email. In full, it read simply:

“From the religious perspective, the Islamic Religious Council of Singapore (MUIS) does not condone any procedure that brings any harm to the individual.

“MUIS advises that female circumcision should only be performed by medical professionals, who will first assess if the procedure is harmful to the client and if she is suitable to undergo the procedure, before carrying out the procedure safely.

“Where harm to an individual can be established in a procedure, it would be prohibited under Islamic law, and MUIS’ view is that Muslims should avoid such a procedure.”

It is the same on-the-fence response that the board has given for years. Not quite supportive of the practice, neither is it a condemnation of it.

According to the Orchid Project, the MUIS definition of “harm” is not one shared by human rights organisations around the world.

“MUIS’ statement suggests that a girl may undergo FGC and remain free from harm, and that cutting can be carried out “safely”,” said the Orchid Project spokeswoman. “We recognise the practice as a form of violence against girls and women, and as a human rights violation, which means that it is inherently harmful.”

Without the religious authority’s support, it’s doubtful change is on the horizon, she added.

“It’s imperative that influential bodies and individuals in Singapore, such as MUIS, recognise the wide-ranging harmful effects of cutting if progress is to be made,” she wrote.

While community engagement remains the most effective method of driving change, she continued, the government has a role to play in helping to fund and promote anti-FGM/C grassroots programmes and initiatives within the Malay community.

“Of course governments do have a role to play in supporting the movement to end FGC,” she added. “We hope to see leaders, policymakers and politicians in Singapore and the world over being advocates for change, and channelling resources and investment into grassroots work to end cutting.”

As Saza continues to push for change, she said that frank conversation about FGM/C within the Malay community could only take the fight so far.

“I think the religious and healthcare leaders have a huge responsibility,” she said. “They should come out and give a clear directive to the Malay community, who depend on direction from religious leaders.”