If they were given a choice, the Rohingya would have stayed in Myanmar – in their home. But “home” is where they face persecution and statelessness. “Home” is where they have been set on fire, raped and killed in multitudes by the Myanmar armed forces. So they escape, choosing exile as the lesser of two evils.

Despite not being a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention nor its 1967 Protocol, India is home to about 200,000 refugees and asylum seekers. The New Delhi office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) told Southeast Asia Globe that there are some 17,000 Rohingya refugees and asylum seekers registered through them across the subcontinent. The Indian government puts the number closer to 40,000 – a figure that both the UNHCR and a number of Rohingya rights organisations have disputed. The truth is likely a number somewhere in between.

Fazal Abdali, senior legal consultant for the Refugee Rights Initiative for the Human Rights Legal Network (HRLN), said that Rohingya had sought refuge in India for years – and, more often than not, they had found it.

“Nobody bothered to know who the Rohingya are, and who his neighbour is – whether he is Rohingya or not,” he told Southeast Asia Globe.

That all changed when the first Rohingya were deported.

In October 2018, seven men held in Assam’s Cachar Central Jail since 2012 for illegal entry were handed over to Myanmar authorities at the border and taken back to their homeland. In January this year, a family of five Rohingya refugees – mother, father and three children – were also deported. Abdali said that many more Muslim refugees other than the Rohingya have been deported – but with little media attention on the issue, he said, exact numbers have been hard to come by.

Farouk — whose name has been changed to protect his identity — is a Rohingya rights activist associated with a Rohingya rights organisation based in New Delhi who wished to remain anonymous, fled Myanmar in 2005. As a Rohingya, he said, he feared persecution in Buddhist-majority Rakhine State – particularly when the armed forces began to target young Rohingya. At first, he found India to be a very peaceful and supportive country, even allowing him to register his organisation and campaign for the rights of his fellow Rohingya. Now, he told Southeast Asia Globe, he fears for the future of his community here.

“Since [the deportations], the Rohingya people are very terrified to live their lives,” he said. “The Rohingya people are living in the fear that they will be deported back to Myanmar, where… the genocide took place.”

Although they may have seemed sudden, the deportations have been the latest blow in a growing campaign of anti-Rohingya rhetoric from the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). In 2017, Minister of State for Home Affairs Kiren Rijiju called the UNHCR registration for refugees ‘irrelevant’ and identified all Rohingya as illegal immigrants, arguing that India is not a signatory of the Refugee Convention.

The same year, a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) was filed in the Jammu and Kashmir high court by Hunar Gupta, advocate and member of the BJP legal cell, and Sunil Sethi, chief spokesperson of the BJP, calling for the deportation of all Rohingya, accusing the minority of being a threat to national security.

Nor has the ruling party stopped at threats. The Ministry of Home Affairs told India’s parliament last month that 230 Rohingya had been detained by border security last year until the end of November – the highest number in four years.

BJP chief Amit Shah summed up his party’s rhetoric on the Rohingya when he said that all illegal immigrants were “like termites eating into the nation’s security”, promising that should BJP be elected again in the upcoming 2019 elections, not a single illegal immigrant would be allowed to stay in India.

“They said, these people are potential terrorists,” Abdali said. “All the Rohingya. Without even thinking that the population might have women, children and elderly people.”

Phil Robertson, deputy director of Human Rights Watch’s Asia division, told Southeast Asia Globe that the deportations were the latest in a long line of anti-Muslim acts by Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his party.

“There is no justification whatsoever for India’s actions against these desperate people,” he said. “Quite clearly, Prime Minister Modi is playing politics, trying to appeal to his right-wing Hindu nationalist supporters by going after the poorest and most vulnerable Muslims he can find. This really sets new lows in shameless pandering and rights violations by Modi.”

For many Rohingya who have sought refuge in India, the threat of being sent back to a nation that despises them has become too much. Farouk told Southeast Asia Globe that around 1,300 Rohingya have already fled from India to Bangladesh in January, where more than 1.3 million Rohingya continue to live in limbo in makeshift camps in Cox’s Bazar.

“Cox’s Bazar is full of crowds, full of refugees,” he said. “But still, nobody is forcing the Rohingya people from Bangladesh back to Myanmar.”

Earlier in February, Bangladesh’s foreign minister AK Abdul Momen said the government has proposed plans for repatriation: a so-called safe zone in Myanmar’s Rakhine state, the very place from which the Rohingya fled persecution and genocide. Momen’s first trip as the new foreign minister led him to India, where he sought Modi’s support for early repatriation – and found it.

But in a recent visit to Bangladesh, Yanghee Lee, The UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of Human Rights in Myanmar, stated that while she does not underestimate Bangladesh’s burden in housing so many refugees, it was clear that they cannot return to Myanmar in the near future.

A sovereign, socialist, secular, democratic republic

Communalism has always been an important part of what it means to be Indian, both politically and culturally. But since early on in the days of imperial rule, religion has single-handedly been used as both a weapon and a shield. And since the BJP government has come into power, a ‘Hindutva” (Hindu-centric) nationalism has hit front and centre.

Though its very own constitution declares it as a “sovereign, socialist, secular, democratic republic assuring its citizens justice, equality and liberty, and endeavours to promote fraternity”, India has not been particularly favourable to its Muslim population.

On 8 January, India’s lower house of parliament passed the controversial citizenship bill that would allow minority groups and illegal migrants citizenship on the basis of religion. The provisions have been made for “Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis and Christians from Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Pakistan.” No provision was made for Muslim immigrants. The bill failed to pass through the upper house this week after facing strong resistance, especially across India’s northeast.

Deportation in a time of genocide

Abdali said that there were a number of factors that had to be considered when sending someone back to the country of origin – especially one that is being charged with genocide.

“First is safe and dignified return, that when you go back you will be treated as a citizen and there will be no atrocities against you,” he said. “Second is voluntariness; it’s their own will to go back.” Were these people given the status of citizen? These are stateless Rohingyas which we are talking about.”

Nor has it been entirely smooth sailing for the Rohingya who have settled in India. The Rohingya are only provided a refugee card by the UNHCR intended to prevent arbitrary arrests, detentions and deportations – though according to Farouk, the provisions are very limited and not much help to the refugees. UNHCR New Delhi told Southeast Asia Globe that “in principle, refugees in India have access to government health and education services, but sometimes they have difficulties in accessing these services.”

When asked about the deportations, the New Delhi UNHCR office took no definitive standpoint on the deportations and chose not to confirm or deny the reports.

“With regard to recent incidents, UNHCR has written to the Government of India to seek confirmation of these reports. UNHCR appreciates the protection afforded by India to refugees and asylum-seekers, and notes the country’s long and proud history of solidarity with people fleeing violence. UNHCR urges the Government of India to continue extending this generosity to Rohingya asylum-seekers and refugees.”

No fences make good neighbours

In addition to appealing to their Hindu base, the BJP’s hardline stance on Rohingya refugees has been driven in part by closening ties between India and Myanmar.

K Yhome, senior fellow at the Observer Research Foundation, said that India’s relationship with Myanmar could be described as “close friends where both sides approach the other with maturity and trust”. Myanmar plays an integral role in Modi’s Act East Policy, a political effort to boost India’s influence in the Southeast Asian region. Similarly, India also plays a mediating role in Myanmar’s ongoing ceasefire agreements in the government’s negotiations with the many non-state ethnic armed organisations in the nation’s border regions.

Yhome told Southeast Asia Globe that strategic objectives had pushed the two countries closer to each other, with both sides wanting to leverage the strengths of the other.

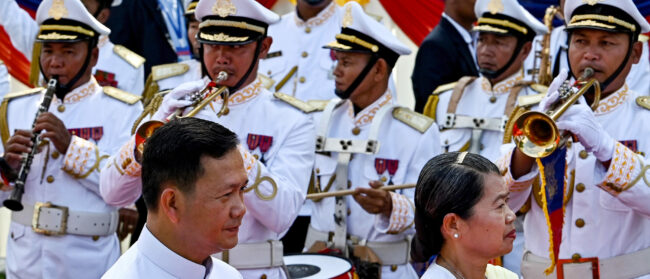

“This deepening relationship is manifested in the frequent high-level exchanges and the growing military-to-military ties,” he said.

In December 2018, Indian President Ram Nath Kovind met with the Burmese President Win Myint. The joint statement from this visit saw the two leaders heap fawning admiration of their efforts towards achieving peace in their countries. Missing from this 23-point statement was anything remotely relating to the issue of the Rohingya people; a careful but calculated omission.

But it isn’t just India tiptoeing around Myanmar about the Rohingya.

“It appears that the ASEAN members are also wary of taking a hard stance on Myanmar because this may allow China to strengthen its hold over Myanmar,” Yhome said. “At a time when internal cohesion within ASEAN face challenges, particularly at a time when China-US rivalry intensifies in the region, ASEAN members want to stand united – and Myanmar is a beneficiary of ASEAN’s desire at preserving the bloc’s unity.”

Before the deportations began, Abdali said, the only wish of the Rohingya was to return to their homeland – though only once the government was prepared to recognise them as citizens. Until then, they had built new lives for themselves in their adopted home.

“They said they have a better life here [in India], better opportunities,” he said. “The people were quite helpful, the communities were helping them out to have a proper life and a lot of them enrolled their children in schools.”

Now, Farouk said, the Rohingya in India have traded one fear for another.

“I cannot directly say that they are doing it because of the religion,” he said. “What I can say is that the Rohingya people are very weak… they are facing genocide back in Myanmar. They don’t even know where they are fleeing to. They are just going wherever they can – just to seek a peaceful life.”