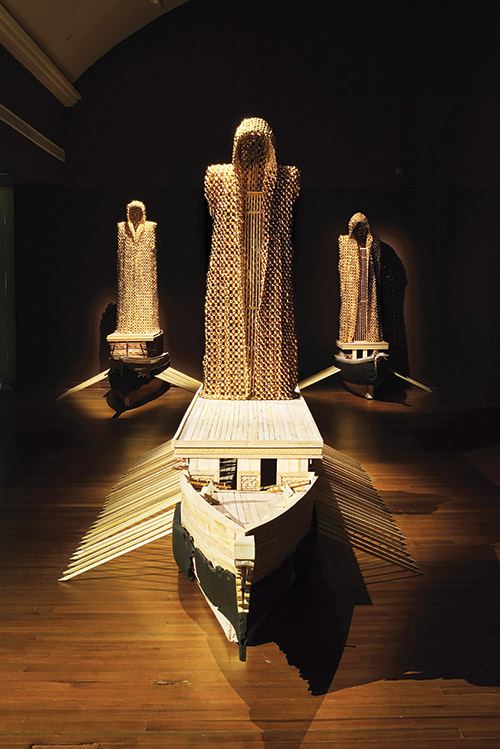

Breaching through the pitch-black wall behind them, three ancient warships emerge into pools of muddled light. Astride their decks, a trio of titanic cowled figures stand in expectation, their hollow robes of gold plate giving stern shape to the empty space of the gallery. Unmoving and unmoved, they nonetheless possess the bearing of an immense inevitability, as ceaseless as the tide that carries them. Their unseen eyes give nothing away.

“History Repeats Itself”, the most recent installation by Indonesian artist Titarubi, is just one of the exhibits in the latest Singapore Biennale that challenges our understanding of Southeast Asia’s legacy as a region torn between ruthless colonial powers and their seemingly endless quest for resources. The empty robes in her work contain only a thin layer of gold – beneath it, the bulk of the garment is made from hundreds of nutmegs, once a precious commodity that drove Dutch and Portuguese powers to pillage the islands of Indonesia.

Speaking to Southeast Asia Globe, Titarubi describes a nation in danger of losing touch with its history. “All the colonialists started in Asia – Southeast Asia,” she says. “But we in Indonesia, we never knew about that.”

Titled An Atlas of Mirrors, the 2016 edition of the Singapore Biennale brings together more than 60 artists and artist collectives from countries across South, East and Southeast Asia to explore the boundaries between place and identity. Centred around the Singapore Art Museum in Singapore’s cultivated arts precinct, the show – stretching from October until February next year – serves as a space for the region’s best artists to forge new narratives for countries that have seen their own histories eclipsed by the wars and horrors of imperialist powers.

According to Titarubi, that process often involves drawing on legends in danger of being lost to modern audiences. In “History Repeats Itself”, the vast warships belong not to some foreign power, but to a 16th-century admiral of the Aceh Sultanate – and the first woman admiral of the modern world. A legendary military commander and diplomat, Keumalahayati drew her ‘Inong Balee’ legion from the ranks of the sultanate’s widows and soon gained a reputation as the guardian of Aceh. For Titarubi, it is this legacy of strength and ingenuity in the face of obliteration to which Indonesia must turn.

“I’m not just talking about the colonialists – that is the past,” she says. “The important thing is to know about the history and to learn from it. And to build up again our culture, before we have none [left]. I think this is the artist’s job. Because artists can imagine.”

According to Manila-based artist Patricia Perez Eustaquio, the darkest days of colonialism in Southeast Asia were driven by the same rapacious greed that now fuels society’s craving for consumer goods. “For me it’s just one reflection of the consumer culture,” she says. “It’s just questioning: why this hunt? And why colonise?”

Reflecting the inevitability of decay, her diptych “The Hunters Enter the Woods” spreads across the grey wall like the wings of a diseased butterfly. A Rorschach inkblot rendered in brushstrokes like blood clots, the work – a pair of mirrored orchids painted in bone whites, bruised purples and sickly greens – references the rare orchids that drove men into the Philippine forests centuries ago in desperate pursuit of wealth. On the left, the critically endangered Paphiopedilum fowliei bears witness to a bleak legacy of deforestation and ruthless collection in the Philippines. On the right, the panel depicts a recently discovered modern hybrid, named after a HG Wells creation by the artist herself as part of the original commission – an orchid that sucks the blood of those that seek it. Unusually for Eustaquio, though, both flowers still cling grimly to life – a departure from her earlier use of flowers in various stages of rot.

“Most of the paintings that I make are of wilted flowers or dead animals… It’s the kind of hunting for a prize and then discarding it, and it’s the idea of consumerism,” she says. “I don’t want to say that I’m moralising our appetite for things – we have to accept that we like things, and then we dislike them – but obviously we see now that there’s very bad effects of too much production and consumerism.”

For other artists at the show, it is the search for identity in the wake of years of colonial and cultural hegemony that drives them. One of five artists shortlisted for the 11th edition of the prestigious Benesse Prize – launched more than 20 years ago at the 1995 Venice Biennale and just this year moved to the Southeast Asian arts hub of Singapore – Vietnamese-born artist Bui Cong Khanh’s work is a deeply personal exploration of the ever-shifting borders dividing nations and nationalities alike.

“This work is talking about my family and my identity and my story,” he tells Southeast Asia Globe.

After growing up in the melting pot port of Hoi An, it wasn’t until Khanh was 20 that his father revealed his Chinese heritage – a heritage kept alive by his father’s profession sculpting wood in the traditional Fujian style. Khanh’s imposing installation, “Dislocate”, uses this ancestral craft to throw into sharp relief the deep divisions between the two nations – and highlight the confusion and chaos facing those caught in between.

From a distance, the artwork resembles the wooden design of a traditional Vietnamese house in its final stages of construction – or one hollowed out by war. A closer look reveals that the bare jackfruit frame is carved in the shape of a chiselled chain-link fence, pulled apart in places as though groaning beneath some great weight. Wrapped within their coils are the mangled detritus of a war that shattered Southeast Asia: the helmet of an American GI, the crumpled coat of a Vietnamese conscript, pistols, rifles, grenades. Hunched in an empty room, the frame is guarded on four sides by doll’s house pagodas of alien design, bristling with cannon and throttled by the thorns of varnished Chinese bonsai.

“I rebuilt the shape to look like a bunker,” Khanh says. “Because this explains the feeling of me. When the Vietnamese and the Chinese were at war in 1979, every village in Vietnam, we had to build a bunker to hide in underground. So when I was a child, I asked my father: ‘Will the Chinese come and bomb me?’ He said: ‘Yes.’”

As tensions between the two nations continued to mount over the years, the people Khanh once counted as friends began to turn on him, twisting his newfound Chinese heritage into treason. It is this hurt that the artist has harnessed in his exploration of the fragility of identity, tracing the shifting cultural markers of a nation that has seen its earliest traditions suppressed by Chinese, French and US colonialists alike for more than a thousand years. And it is from this maelstrom of tortured traditions that Khanh is quite literally carving a new understanding of what it means to be Vietnamese – one that breaks down the ingrained certainties of centuries past.

“My work connects with the past and the present, but I try to do something for the future,” he said.

For emerging Thai artist Pannaphan Yodmanee, also shortlisted for the Benesse Prize, which will be awarded next month, wrenching the future from the clutches of the past pits her against those for whom the status quo has long been considered beyond reproach. Her work challenges the moral authority of institutions that hide behind the veneer of piety while perpetrating crimes of bigotry and oppression.

“They think that religion, that Buddhism in Thailand is untouchable,” Pannaphan says of her critics. “They respect the image, the Buddha image, more than the thoughts from the Buddha. And my work – I make Buddhism touchable, combine it with science.”

Bleached and faded, her imposing mural “Aftermath” depicts a dystopian wasteland peeled back to reveal ruptured concrete criss-crossed with ribs of rusted iron. Figures from the depths of Buddhist cosmology crawl beneath a sky studded with stars as ordered as lines of code: hungry ghosts slithering toward a woman twisted in dark sensuality, shrunken mouths puckered as sphincters, the flayed king of decay tearing at his skin with a haggard white hand. Spilled across the floor, discarded stupas stand in various stages of ruin. An unflinching depiction of a world ruled by suffering, it is little wonder her work has provoked a stern reaction from Thailand’s authoritarian military regime.

“Last time I had an exhibition in Bangkok I was [criticised] by the government,” Pannaphan says. “I was using a Buddha image with no head.”

The struggle to wrest a new national identity from stagnant tradition – and those who would twist it to their own ends – is one that Southeast Asian artists have felt all too keenly. Reflecting on the difficulty of his task, Khanh was philosophical. “We are now,” he says. “So we have to do something for this time, for this history.”

The Singapore Biennale runs until 26 February 2017.