Photography by Omar Havana

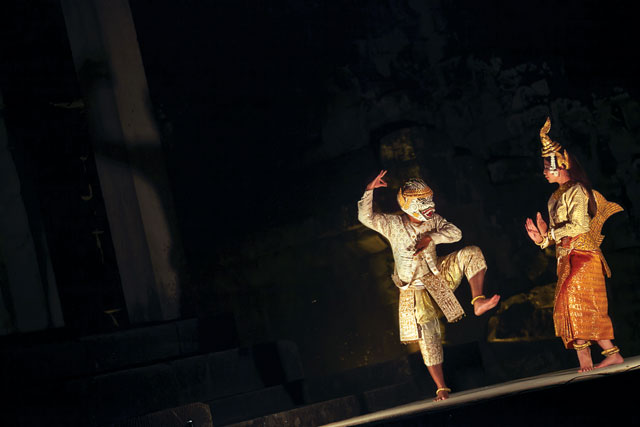

The dancers move gracefully in perfect, slow unison to a melodious mix of cymbals, xylophones, drums, reeds and a chorus of human voices. Their elaborately sequinned and brocaded costumes dazzle in the light as they pivot, their fingertips touching their forearms as though their wrists were made of rubber. Their arms, ankles, waists and hair are clasped with gold. Each wears an elaborate towering crown. Their movements are hypnotic, mesmerising the crowd with ethereal glamour and poise.

Any visitor to Cambodia will notice the thousands of Apsara dancers adorning the stone walls of Angkorian temples. These Hindu spirits of cloud and water traditionally represented the paragon of feminine beauty, elegance and refinement.

They are heavenly nymphs that dance and entertain, seducing both men and divinities.

Their mortal counterparts have been an integral part of the Cambodian court for more than a thousand years, with temples hosting troupes of dancers that could be summoned in order to please the gods. Kings themselves enjoyed their charms, with large royal harems being composed of classical dancers until the middle of the 20th Century.

The art form is generally called the Royal Ballet of Cambodia, and it shares many similarities with classical dance elsewhere in Southeast Asia. Common performances include interpretations of the Reamker, an epic Cambodian poem adapted from India’s ancient Ramayana. While most dancers are female, men play a few crucial roles. In any dance, each movement and gesture is steeped in symbolism.

Along with other artists and intellectuals, many of Cambodia’s classical dancers were purged in Pol Pot’s agrarian revolution.

What was once an art reserved exclusively for festivals and the enjoyment of royalty became public under the reign of the recently deceased King Norodom Sihanouk. Sihanouk released the Royal Ballet from the confines of the palace, and included performances in several of his films.

The Royal Ballet of Cambodia dazzled visiting heads of state and common Cambodians alike until 1975, when the Khmer Rouge came to power. Along with other artists and intellectuals, many of Cambodia’s classical dancers were purged in Pol Pot’s agrarian revolution.

Classical Cambodian dance began to be revived in the 1980s and 1990s, due in large part to the efforts of one of Sihanouk’s daughters, Princess Bopha Devi, who served as the prima ballerina of the Royal Ballet of Cambodia until 1970. Today, the ancient art form is kept alive largely thanks to a host of cultural institutions in the US, France and Cambodia. Even Cambodia’s current king, Norodom Sihamoni, is a classically trained dancer who both taught and choreographed traditional Cambodian ballet in Paris for nearly 20 years before ascending his country’s throne in 2004.

There are many opportunities to see traditional Cambodian ballet while visiting the Kingdom. The pictured performers were captured at the Raffles Grand Hotel d’Angkor, which hosts Siem Reap’s most luxuriant Apsara show. The historic hotel’s peaceful gardens are home to the Apsara Terrace, where a majestic performance awaits along with a pan-Asian barbecue on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays. Meanwhile, another of temple town’s finest hotels, Residence d’Angkor, offers a similarly captivating dance experience on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays.

In the capital, an excellent troupe of musicians and dancers educated by cultural non-profit organisation Cambodian Living Arts performs a classical programme called Plae Pakaa every Friday at 7pm at the National Museum. The capital’s Sovanna Phum Art Association also hosts a rotating roster of traditional performances every Friday and Saturday at 7:30pm.