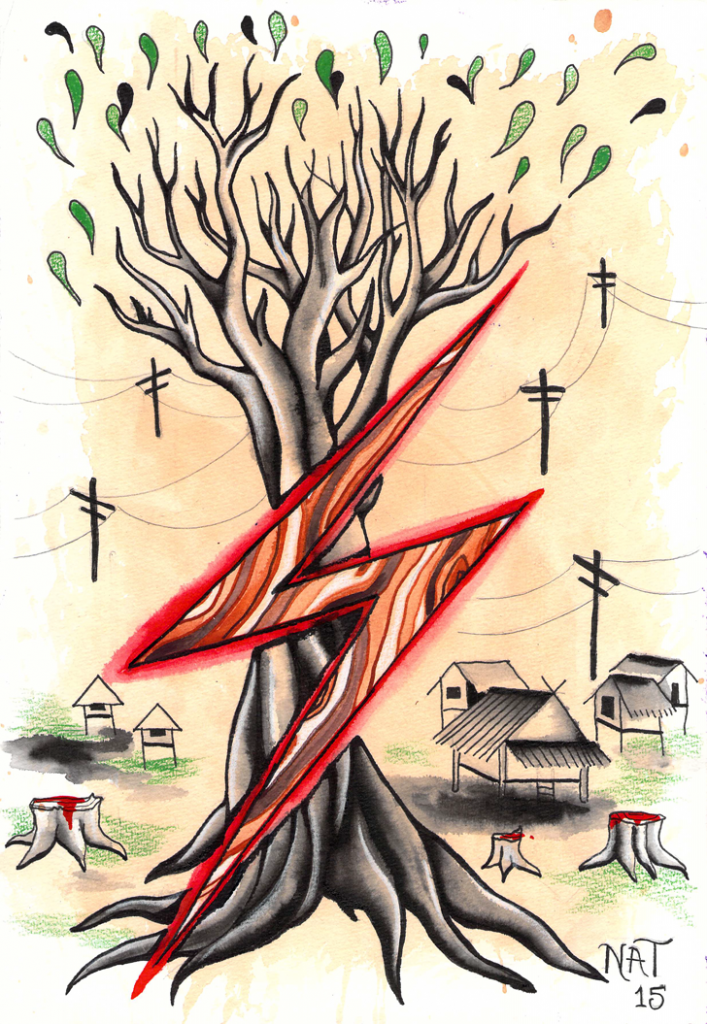

In a nation where the cogs of development turn slowly, Lao authorities are taking precious rosewood trees from impoverished villagers as payment for essential services

In Laos, one of the world’s least developed countries, people living in rural areas are bearing a high cost for being connected to the modern world. Villagers in Bolikhamxay province, central Laos, say their families have been forced to pay for electricity and roads with the one currency available to them: trees.

Électricité du Laos (EDL), the state-owned national energy company, began connecting homes in the area to the electricity grid about eight years ago. According to a man who gave his name only as Boun, due to fear of reprisals, households each had to hand over five hardwood trees, usually endangered rosewoods. “They ask each family if they want electricity and then check people’s gardens to find big trees,” he said.

Boun’s wife, Sao, remembers EDL filling the local schoolyard – about two hectares – with piles of logs collected in the area. “It took five to six months for the logs to be trucked away, they were so big and heavy,” she said. “Then the Department of Forestry took what was left behind as payment for fire protection.”

Trees, it seems, are legal tender. Yet the local people are paying for electricity with timber worth far more than their own homes – the valuable rosewoods dubbed “exchange trees” by the villagers. Rosewood is a highly sought after luxury wood and fetches about $50,000 a cubic metre in China, according to the Environmental Investigation Agency.

The Department of Forestry claimed in 2010 that forest covered 40.3% of land in Laos and insists that this figure, which amounts to 9.5 million hectares, remains accurate to this day. Yet independent observers, such as the World Resources Institute (WRI), report that the country’s forests are being decimated. The WRI calculates that Laos has only 9% of its primary forests left and lost more than 1.6 million hectares of tree cover between 2001 and 2014.

The existence of commercial and illegal logging industries in the country is well documented. A report by the environmental group WWF, leaked in late October, revealed there has been an explosion in the illicit trade and implicated government officials in it.

The group’s analysis of customs data found a huge disparity between the timber Laos recorded as having been exported and the amount that China and Vietnam – which together accounted for 96% of Laos’ $1.7 billion in timber exports last year – actually received. In 2013, the report states, Laos exported 1.4 million cubic metres of timber to the two countries: more than 10 times its official harvest.

Most reports on deforestation in corruption-riddled Laos focus their attentions on well-connected companies such as Phonesack, which has close ties with senior members of the government, while others detail the not insignificant role of the Lao and Vietnamese armies.

It is not just such members of the elite who are pillaging the country – nominally communist but more akin to an authoritarian fiefdom – of prized hardwoods. State-owned firms such as EDL are on the take too.

“They want the ones where two people holding hands can hold the bottom of the tree,” said Boun. “Without five trees, they charge you lots of money. When we got the electricity, all our big trees suddenly disappeared.”

The practice dates back to 1975, when the nation was still emerging from the horrors of civil war and the US bombing campaign. At a time when few people had cash, and the tax base was insufficient to build public facilities, the Ministry of Public Works and Transport accepted hardwoods as payment for building roads to remote areas.

The problem, explained Boun, is that the state-owned firms never stopped requiring villagers to exchange trees – even after a prime ministerial edict was introduced in 2008 prohibiting the harvesting of domestic rosewood species, followed by another in 2011 banning the trade and export of rosewood timber.

“Before the roads and EDL, people got about 90% of their food from the forest. They looked for mushrooms, bamboo shoots, leaves… Some they would sell to buy rice and salt,” said Boun. “They had river fish. Wetlands provided snails, crabs, eels and lotus roots. Now the wetlands and fish have gone.”

“The people needed roads to get to and from schools and markets. At first, no one really noticed the trees had gone – we had plenty more. But now the demand for trees [has] increased.”

EDL and the Ministry of Public Works and Transport did not respond to requests for comment.

Among NGO workers striving to save what is left of the country’s trees and forests, disenchantment about the rapid felling of timber is widespread. Like Boun and Sao, most of those willing to speak to journalists about the issue are not prepared to risk their safety by revealing their identities.

“We spend a fortune in taxpayers’ money trying to save a small area of forest,” said a consultant with a German-funded Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD) project. “When the project is over the people or the army will log the area. I don’t know why we bother. We can hear the chainsaws nearby. They pay the men $20 to work all night felling trees. They give them yaba [methamphetamine] so they can keep working.”

A former farmer, now living in Vientiane province after he was relocated from his land to make way for a Chinese dam, said he cuts trees for EDL. “If the government doesn’t give a shit, why should I?” he asked. “This is not my land. [Mine] was lost under a dam. I can’t make a living [from farming], so I exchange trees.”

In Bolikhamxay, Boun and his fellow villagers are facing a new problem: their access road needs to be repaired following heavy rains. “We have discussed it with the Ministry of Public Works and Transport, and it looks like we will have to sacrifice all our remaining trees to get the road remade,” he said.

He alleged that village and district-level officials, who are all members of the ruling party, take a cut of such projects in order to top up their meagre government salaries. The village head, for example, is also a party member and earns just $10 a month.

“When the district decides to connect a village to roads and electricity they check out the community forest and assess which trees to take”, ostensibly to make way for the road, Boun explained. “They make calculations, but we know the calculations are for their benefit.”

David Dent, a watershed management specialist working with a foreign aid project, said illegal logging in the country was damaging not only the environment, but also the country’s people.

“We all know that rosewood is cut by villagers, by officials and by the army,” he said. “Vietnamese and Chinese [companies] obtain concessions to build a dam, coal or iron ore mine despite lack of mineral evidence. Then they log the forest and say: ‘Oh gosh, it didn’t work out,’ taking millions of dollars in trees… Under the Lao government, poverty has increased along with the amount of fake data. There is no concept of the future if the present means you have an empty belly.”

Keep reading:

“Absolute power” – Geopolitical tensions over Laos are on the rise, particularly given its unflinching approach to the construction of dams on the Mekong River