The bell rang. My quarters had no electricity. In the dark there was only the sound of crickets and the throb of aching limbs – I had been sleeping on a concrete slab for weeks.

It was close to the end of a month-long stay at Down Kiem, a forest hermitage attached to the famous Suan Mokkh monastery in Thailand, and walking through the forest at this hour necessitated a torch to check for snakes that like to mimic fallen branches.

The monks at Down Kiem are meditation masters and revered for their asceticism. They are rumoured to possess powers of insight, endurance and even levitation. They choose to live deep in the forest so they can be close to nature. After three weeks my mind was clear, and the modern world seemed like a feverish dream.

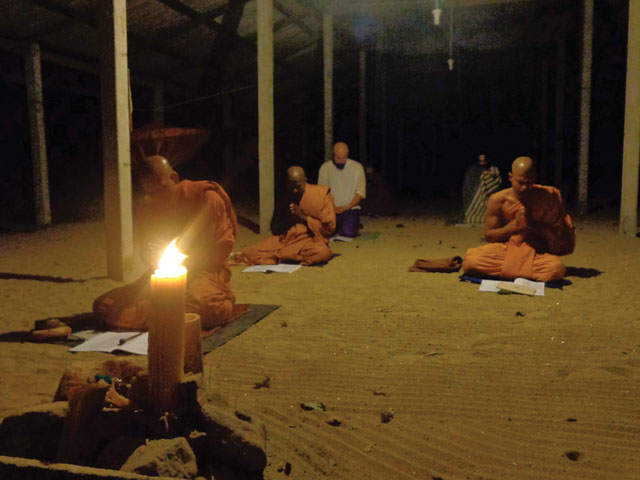

Soon there was a hall in a clearing: a roof on stilts with sand for a floor. Three monks and a few laymen were already sitting cross-legged. There was a fourth monk residing at Down Kiem but he was fasting deep in the forest – an ephemeral stick figure amongst the trees who rarely made an appearance. Ajun Medi, the head monk, lit a candle to begin morning chanting and meditation.

The monks at Down Kiem practise a type of meditation called anapanasati, which means ‘mindfulness with breathing’. The monks use it to attain mystical insight that leads to a state of bliss called Nirvana.

Dhammavidu is 60 years old and has the mannerisms of a child lost in a daydream, yet this odd, British monk’s mind is clear and his answers pitch-perfect. He lives in a wooden hut on the mountainside and spends every afternoon pacing up and down his balcony. “I like to spend my time walking up and down. The movement keeps my mind in a certain place,” he said. “I might do some translation in the morning but the rest of the time I pace.”

He was reticent at first, but soon came around to discussing anapanasati. “There are many practices that get attributed to the Buddha but anapanasati is something else…” he trailed off as if remembering something. “I mean, if you practice this stuff, I mean really practice it exactly as taught, you will see that it was no ordinary human mind that put this system together.”

As the sun rose I focused my attention on the tip of my nose in order to feel the sensations made by the air as it was drawn into my lungs and expelled. This simple task is the basis of anapanasati. “Learning meditation is no different to learning an instrument,” said Dhammavidu, who used to be an accomplished Spanish guitar player.

Ajun Medi is 53 but appears to be in his thirties. He’s a practical, hardworking man who speaks with the straightforwardness of a teenager. “Anapanasati makes you happy and lets the mind calm down,” he said. “It also increases your sensory acuity and gives you more power and strength”.

Aside from the practical benefits there is plenty more to be had. “Anapanasati is a step-by-step system that will take you all the way to full enlightenment,” said Dhammavidu. Along the way, practitioners pass through stages known as jhanas. These are altered states of consciousness produced by effective meditation.

When entering the first jhana the body can be engulfed in tremors and shakes as if a storm was raging in the practitioner’s cells. After that, a sensation best described as blissful pins and needles – known as piti – washes over the body. “Some people take drugs and think that’s similar,” said Dhammavidu, who was a hippy in the 1970s. “But if you experience piti and the other jhanas you will know they are better than any drug.”

The day was still fresh when a monk and I left for the daily alms round, each carrying a four-layered tiffin tin. Every year Ajun Medi goes to the local village and asks for volunteers to cook for the monks. “The Thai people get rid of selfishness by giving food to the monks,” said Ajun Medi. “They don’t have time to practice meditation so they support the monks and in return we give them Dharma talks [Buddhist sermons] and chant for their ceremonies.” The five-mile alms round trip was draining. Our only meal for the day – rice with curry as hot as magma – was a gratifying welcome home.

After breakfast came chores. “Always be mindful when you are working,” said Ajun Medi, “then peace will come.” Mindfulness, as anyone who has read Eckert Tolle or watched certain TED talks will know, is about being in the present moment. At the monastery there is always work to be done. One can practice mindfulness by focusing purely on the work in hand: no whistling; no fantasies about the future or misty reminiscences; just pure awareness of the broom and the sound of sweeping. When this is achieved, time dilates and the sweeping seems to happen by itself.

After chores, the really intolerable heat began. It necessitated escape to the cool concrete of the monastery building where there was a small library. On the door was a sign. “For the use of Down Kiem residents. No sleeping. No insane persons,” it said in 1970s-style bubble writing, which made me wonder if Dhammavidu had made the sign – he was fond of branding modern society as “insane”. Inside were a collection of Buddhist tomes in English and Thai and a few shelves of paperbacks left by previous residents. The usual hippy favourites were present and correct: Joseph Campbell, Herman Hesse and Deepak Chopra.

But it’s not only hippies and rootless intellectuals that frequent Down Kiem. There was Dieter, a German doctor who would shake his head and fail to describe the horror he had witnessed working in a Johannesburg accident and emergency department. He was at Down Kiem trying to find answers. Juan, on the other hand, was a happy-go-lucky fireworks display organiser from Peru.

With no lunch or dinner the afternoon was unbroken. Rather than filling time, time filled me. I watched butterflies circle in patches of sunlight; how my fingertips swelled with moisture while in a hot spring. Being close to nature is very important to the monks of Down Kiem. “We don’t need temples and gold statues,” said Ajun Medi. “We just need nature. If you see nature then you see the truth.

“Instead of a fancy stupa, we have a termite stupa,” he chuckled. The “termite stupa” was a 2.5-metre high termite colony in the woods. The monks had made a clearing there, which they tended with candles and incense.

Later that afternoon I left on a bicycle clutching a list of things to buy from the village, my first expedition outside since arriving. The village was difficult to find; a large Tesco Lotus presented itself. Meditation and ascetic living tends to make the mind and body incredibly sensitive. Inside, everything seemed creepy and artificial, like bad CGI. The thousands of shiny packages were overwhelming. On my way out an ice cream parlour crept into my peripheral vision. The ice cream hit my system like crack cocaine – fast, euphoric and instantly addictive.

It was evening when I returned, the plastic bag swinging from the bicycle. It was time for the final meditation session of the day.

A famous meditation teacher once said that meditation is mostly a process of making the mind more and more sensitive; that it will become so sensitive it will pierce through all illusions and see the ultimate truth of Nirvana.

“I’ve been practising this stuff for 20 years and I can’t say I’m fully enlightened,” said Dhammavidu. “I think anyone who goes around saying they’re fully enlightened is proving they’re not. But I have experienced a partial awakening and do you know what I realised? The great truth I found? Nature is nature.”

He chuckled at my confusion, seeming to relish it. I guess some great truths just can’t be put into words.