The widespread speculation that Russia has considered deployment of chemical weapons in Ukraine has brought renewed attention to the use of chemical defoliants by the United States during the Vietnam War, and whether or not their use qualifies as chemical warfare.

The U.S. government has argued liquids causing defoliation and damage to food crops during the Vietnam War, known as Agent Orange and Agent Blue, were not chemical weapons since they were not meant to kill human beings. The United Kingdom, which used herbicides during the ‘Malayan Emergency’ conflict from 1948 to 1960, has supported the U.S. interpretation.

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February, the U.S. government has repeated its denial of past chemical weapons use. In response to Kremlin claims of American chemical weapons being deployed in Eastern Europe, an 18 March Facebook post by the U.S. embassy in Hanoi stated: “FACT: Russia, not the United States, has a long and well-documented track record of using chemical weapons, including in attempted assassinations and poisoning of Putin’s political enemies like Alexey Navalny. The United States does not have chemical or biological weapons programs in Ukraine. The Russian government needs to #StopTheLies.”

The mutual accusations between the U.S. and Russia recall a little-known Cold War story about a Polish diplomat and Soviet ambassador in Hanoi preventing North Vietnam and China from launching a campaign against alleged U.S. chemical warfare.

Poisoned history

In 1962, guerrillas based in the southern regions of Vietnam noticed American helicopters and low-flying aeroplanes spraying liquid over forests and rice fields. Leaves fell off the trees, food crops died and the health of local people suffered. This frightening news was communicated to leaders in Hanoi, who wanted the Polish representative on the International Control Commission for the Geneva accords to protest against U.S. chemical warfare.

A 1954 conference in Geneva had divided Vietnam temporarily between North and South. An international control commission, which was established with members from India, Poland and Canada, still existed in 1962 and was entrusted with responsibility for monitoring a new Geneva agreement on Laos.

North Vietnam pursued a policy of peaceful reunification between 1954 and 1956 based on a belief that a pledge made in Switzerland to hold national elections in all of Vietnam before July 1956 would be respected. When the date passed and there were no elections, a new communist insurgency took off in South Vietnam with support and leadership from North Vietnam and assistance from China and the Soviet Union. The insurgency led to a political crisis in South Vietnam and a massive U.S. military intervention.

The U.S. got its ‘Vietnam War’ and Vietnam had its ‘American War.’

North Vietnam sent weapons and provisions to the South by ship and through a network of dirt roads in the jungles of Laos, Cambodia and the highlands of Central Vietnam, a transportation system baptised as the ‘Ho Chi Minh Trail.’

The U.S. began to spray chemicals in the jungles where insurgents operated. While the dioxin in the agents did not bring immediate death, exposure could cause skin disease, liver problems, diabetes, immune system dysfunction, nerve disorders, muscular dysfunction, hormone disruption and heart disease, along with horror and fear.

North Vietnam and China asked communist Poland’s control commission representative to protest U.S. chemical warfare.

Communist propaganda

The head of the control commission’s Polish delegation was Professor Mieczyslaw Maneli, a legal scholar who survived detention in the Auschwitz concentration camp during World War II and at one stage was liberated by communist commandos. He became dean of the University of Warsaw law department before being sent to Indochina, serving his second term in 1962.

On his way to Hanoi, Maneli met in Beijing with Chinese Prime Minister Zhou Enlai, who told Maneli the Americans were trying to exterminate the Vietnamese people by means of chemical warfare. This is genocide, the same crime for which the the fascist German and Japanese were put on trial, he said.

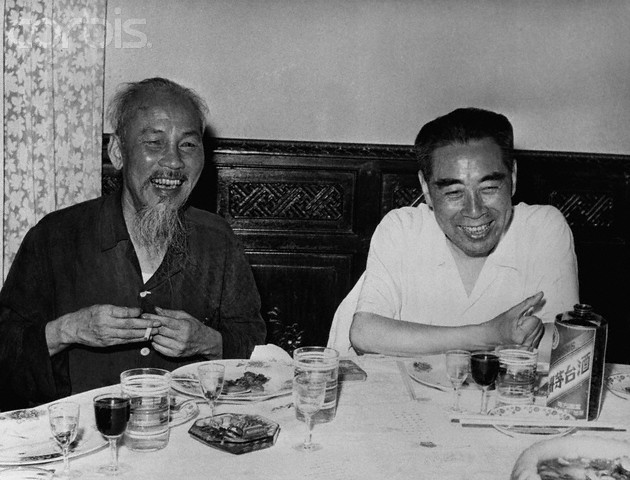

In Hanoi, Maneli met with President Ho Chi Minh, who also claimed the Vietnamese people were being exterminated by chemical means.

When asked to denounce the U.S. for conducting chemical warfare in violation of the 1925 Geneva protocol, Maneli became suspicious and demurred. He was familiar with communist propaganda and wanted proof before raising the serious accusation with the commission.

Maneli asked for evidence of spraying not only leading to defoliation but poisoning people in South Vietnam. When no such evidence emerged, Maneli concluded his Vietnamese comrades must have invented the story to wage an ideological campaign. Maneli remembered how North Korea had falsely accused the U.S. of conducting bacteriological warfare in the Korean War. He discussed the matter with the Soviet ambassador to Hanoi, who agreed that evidence was needed. The matter was never raised with the full commission.

Poland’s communist leader Vladyslaw Gomulka would later criticise Maneli for failing to carry out party policy and not approaching the matter in a political manner, but rather in a “formalistic style.”

Maneli was among 13,000 Jews driven out of Poland in a 1968 anti-Zionist, anti-Semitic campaign. Many emigrated to Israel, but Maneli crossed the Atlantic and took up a professorship at Queens College in New York City.

He published a 1971 book about his Indochinese experience: “War of the Vanquished.” The title played on the ability of Vietnamese communists to persevere and expand their armed struggle each time they lost a battle.

Maneli also told the story of how he declined to take part in a trumped-up campaign against U.S. chemical warfare and his book provided his account of the chemical weapons discussions.

Operation Ranch Hand

In 1971, Maneli could feel proud of his refusal to raise false accusations against the U.S. At the time, the war in Vietnam was still raging and few people knew about the harmful effects of the American defoliation campaign.

Operation Ranch Hand began in 1962 and ended in 1971, after repeated spraying of huge tracts of South Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. The primary purpose was to defoil trees so American forces could detect the actions of their adversaries on the ground and destroy food crops in areas controlled by the enemy, forcing the inhabitants to move to government-controlled areas.

While defoliation was mainly the result of Agent Orange, Agent Blue was used to damage food crops. Both of these substances left highly poisonous dioxins in the ground. Over a period of years, many people who were exposed developed various types of cancer, while babies born in the affected areas suffered serious physical defects.

Many victims of the airborne chemicals belonged to Southeast Asian ethnic minorities, while others included soldiers fighting on all sides: local guerillas as well as North and South Vietnam soldiers and American GIs.

Professor Maneli’s reactions to the revelation of Agent Orange’s long term effects are not clear. In 1982, when the U.S. Air Force released an official history of Operation Ranch Hand. In 1991, when the American Congress adopted the Agent Orange Act, making affected U.S. war veterans eligible for compensation. Or in 2009 when the U.S. Supreme Court rejected a lawsuit by Vietnamese victims against the major American producers of the chemicals.

Maneli died in 1994, long before the U.S. finally began in 2010 to clean up dioxins at its former air base at Da Nang in the current Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

Maneli’s coverage of chemical warfare in his 1971 book is paradoxical. On the one hand, he was right to be suspicious of communist propaganda and, as a legal scholar, to demand hard proof. Yet he was wrong to dismiss Vietnamese reports of harmful spraying.

Maneli was a great humanist, a philosopher of law, a man deeply concerned about ethics. But his scepticism contributed to preventing the world from discovering the crimes conducted as part of Operation Ranch Hand.

When perpetrators know about the harmful effects of concentrated dioxins, it seems reasonable to characterise the destruction of populated forests and food crops through spraying as a kind of chemical warfare.

The use of Agent Orange and Agent Blue during the Vietnam War should qualify as a crime against humanity.

Stein Tønnesson is a research professor with the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) and the author of “The Vietnamese Revolution of 1945” and “Vietnam 1946: How the War Began.”