The latest chapter of Joe’s life began with the old one still only half-written. In April 2021, he packed a bag, left his beloved dog with friends, and locked up his apartment in downtown Yangon, his head reeling from the speed with which his life had grown unrecognisable.

In the space of two months, he had gone from an anonymous, upwardly mobile millennial working in policy research to a target on the military government’s wanted list – and deciding whether to flee the country.

Thousands of Myanmar’s young people have found themselves tormented by the same question – whether to stay or to leave – in the aftermath of last February’s coup. The upheaval has been devastating for a generation who came of age during a time of relative prosperity, including economic liberalisation and the election of the National League for Democracy (NLD) in 2015.

But for those who have managed to leave, safety has not necessarily meant a return to stability or normalcy.

Shortly after the coup began, Joe’s name and photograph began circulating on social media in a conspiracy theory spread by pro-coup supporters. The posts accused him of being part of a plot, together with researchers in international development and colleagues from the non-profit organisation he previously worked for, to ‘sell’ Myanmar to American billionaire George Soros.

Joe, 32, who took part in the Spring Revolution protests after the military seized power on 1 February, was initially more bemused than upset, believing the posts would disappear before long. The thought of leaving Myanmar never crossed his mind, even as the military intensified its crackdown and he went into hiding, moving between friends’ houses for several weeks.

As texts kept flooding in from concerned friends and colleagues, he began to have second thoughts. When a rare opportunity to leave came up – a former colleague offered to help him apply for a humanitarian visa scheme offered by the U.S. – he spent a month agonising over what to do. At his family’s urging, he eventually decided to go.

He landed in the U.S. on 4 July, as the nation celebrated Independence Day.

“Never in my life would I have imagined doing this,” said Joe. “It was my family who said to leave if I got a chance, because you never know when you could be arrested. That’s the only reason I did it.”

Weighing options

Even with the country’s long tradition of migration, the scale of the post-coup exodus has prompted experts to call it a “Myanmar migration moment”. While Rohingyas make up the vast majority of Myanmar’s estimated 1.2 million refugees and asylum-seekers, according to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), around 19,000 people had fled to neighbouring countries like Thailand, Cambodia, and India by January 2022.

The real number is likely to be much higher, even before including those who, like Joe, made it farther afield. During a spate of intense fighting in December 2021, around 3,900 people were estimated to have poured into the Thai border town of Mae Sot within a week. Many migrants are likely to be semi-documented or undocumented, making accurate figures or official demographic data hard to obtain.

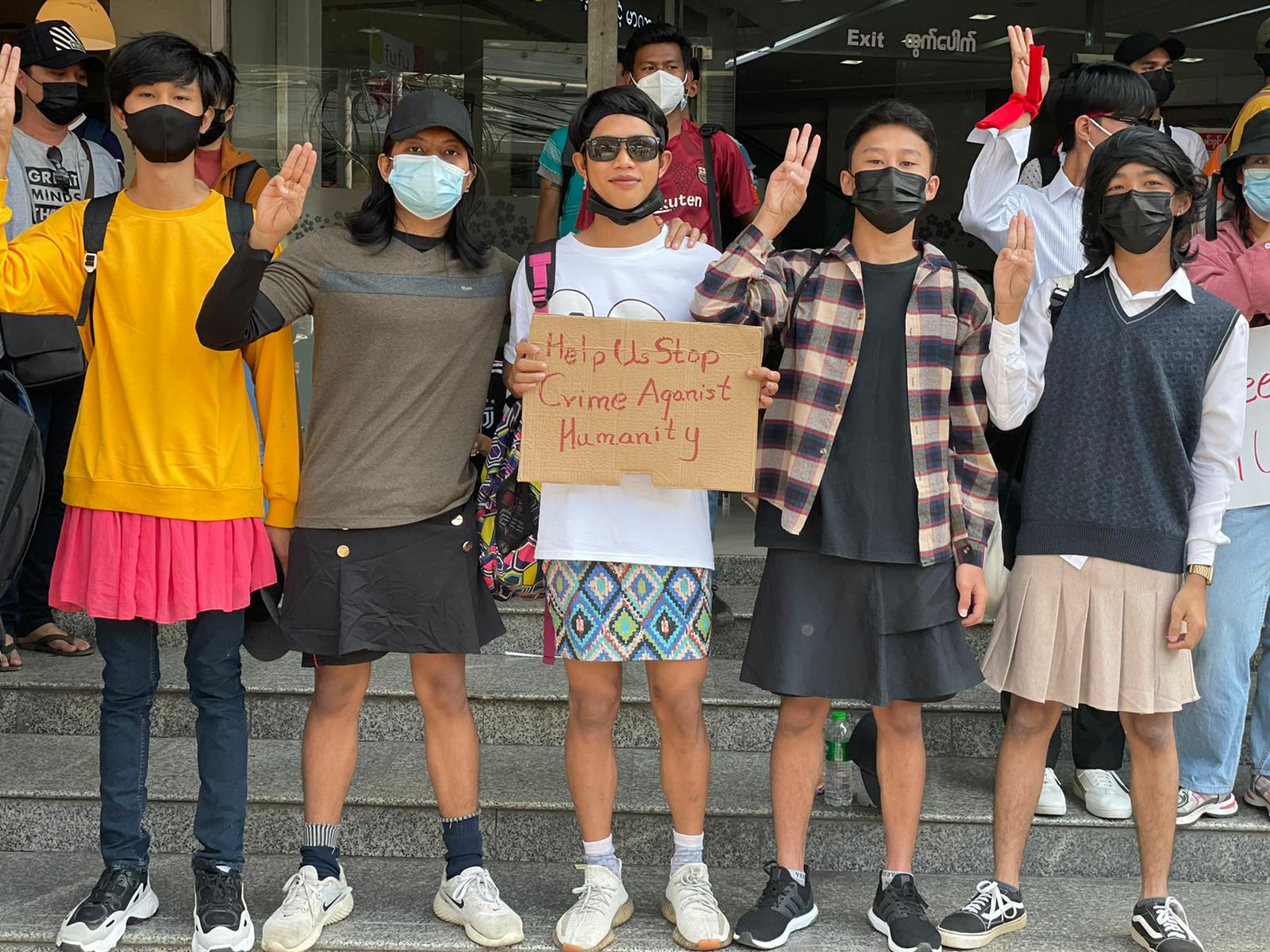

At the start of the Spring Revolution, Myanmar’s youth were lauded for leading the resistance movement, powered by a refusal to return to the turmoil of earlier generations and hope that a freer society might be born of the conflict, but sustaining that optimism looks increasingly difficult.

According to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, a human rights organisation, over 1,700 civilians have been killed and 10,000 detained since the start of the coup. Security forces have shown no qualms about using lethal force to quell resistance, with the leader of the Tatmadaw, General Min Aung Hlaing, vowing to “annihilate” any holdouts.

Those fleeing might find themselves free of such brutality, but faced with a new set of practical and emotional challenges. While individual experiences of exile vary hugely, those uprooted can find their initial relief quickly tempered by uncertainty over their immigration status, financial precarity, and culture shock, as well as anxiety, guilt, and loss.

Amongst those trying to find their feet are students hoping to continue their education and workers whose livelihoods have been upended. Min, 23, who moved to Thailand last July with five colleagues, is one of them. Like Joe, he was a beneficiary of the country’s boom years, juggling studying for a certificate in Peace and Conflict Studies and a full-time job when the coup broke out.

When the education company he worked for in Yangon ceased domestic operations in mid-2021, his boss relocated the group to Pattaya, later moving them to Bangkok.

As he entered Thailand on a tourist visa, which does not give him the right to work, Min found a second, under-the-table job to cover his expenses. Being semi-documented has its difficulties: he cannot open a bank account without immigration authorisation, and finding work that will sponsor a visa is almost impossible as he does not speak Thai. He does not dare approach the Myanmar embassy in Bangkok for fear that his details will be passed to the military.

“I think a lot about my future, like what’s going to happen next, if I am able to find a job … Then I think I was lucky enough that I managed to move here,” he said.

“But I’m also very stressed every time I think about things. Right now, I’m not in a position to go back home or go anywhere.”

“I haven’t lost anything yet”

The stress of trying to start over in a foreign environment, along with isolation, post-traumatic stress from witnessing or experiencing violence, and worrying about loved ones left behind at home, exposes migrants and refugees to a uniquely vicious range of mental health stressors.

As Joe settled into his new life in the U.S., Myanmar was being battered by the second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic. Two weeks after he arrived in early July, he got a call: his father had fallen sick and passed away.

“It was crazy. My dad got Covid, then two of my sisters got Covid, and then my dad passed away. This was when Covid was going crazy in Myanmar and at the time the military seized all the oxygen and it was so difficult to be hospitalised because of the bureaucracy…” he said. “It was so tough with me being here.”

I’m not fighting there with my other friends… even now, I still feel selfish.”

Joe, Myanmar refugee in the U.S.

Social media, while a lifeline to family and friends and a key means of keeping up with the news from home, is also riddled with horrific glimpses into the conflict.

“I’ve been using social media a lot, but it’s all disturbing news and I dream about them every night,” said Min. In December, he sought medical treatment after reading about a massacre of civilians in Kayah state caused him so much distress that he had trouble sleeping and eating for days.

Their relative good fortune came with another sting in the tail: survivor’s guilt. Like many others who managed to leave, Joe and Min found themselves tormented about whether they had abandoned those who stayed.

“I’m trying not to see myself as being selfish, but that’s how I felt. I’m so selfish to leave the country, I’m not fighting there with my other friends,” said Joe. “Even now, I still feel selfish.”

“When I talk to others here I feel really guilty, because right now I’m still okay in Thailand,” echoed Min. “I have money and I have everything I need, but some of them don’t really have any idea what’s going to happen, if they can find a job or have a place to stay. ”

Joe and Min were candid about being better placed to start over than most. Their middle-class backgrounds have given them advantages many others can only dream of, including a good grasp of English, university degrees, and previous experience living abroad.

Although they have to be frugal, they have also been receiving financial help. Joe receives a stipend under the terms of his visa, while Min’s boss has been paying rent and a transportation allowance for the employees in Thailand (although he doesn’t know how long this will continue). Both got mRNA Covid vaccines free of charge in Thailand and the U.S.

However, their families remain in their hometowns in central Myanmar, with no prospect of being reunited any time soon. While some of their friends have continued with life in their hometowns, others have gone into hiding, joined resistance groups like the People’s Defence Force (PDF) or EAOs, or been sent to prison for opposing the coup.

Leaving has also strained their relationships with friends who remained behind. Joe and Min are reluctant to share about their circumstances for fear of judgement or seeming insensitive.

“Some of my friends don’t know that I’m here in the U.S…I only told a few people that I’m out here because I don’t want people to think ‘oh okay, you’re there, your life is better’,” Joe said. “I want to recognise my own stress, but at the same time I don’t want to publicise what I’m doing.”

Indefinite exile

Things aren’t all relentless gloom. In mid-March, Min went on a spontaneous trip to the Thailand-Cambodia border with friends, sending photos of the train journey via Telegram. Joe cracked jokes about the “good” negative 2 degrees Celsius (28 degrees Fahrenheit) weather and the “midwest grannies” in his new home, a college town.

“It’s kind of a bubble and open-minded,” he said. Although Trump flags come into view if he drives beyond the city limits, the town itself is racially diverse and people have been warm and accepting, for which he is grateful.

“I’ve lived abroad from time to time so it’s not been a huge adjustment for me,” he said. “I feel safe since I got here and I’m not at risk. I know what I need to do to survive, it’s just my family I’m worried about. If my sisters are happy, I’m happy.”

Although his visa does not allow him to work, he keeps busy with volunteering, research for climate justice projects, and going to the gym. He got his drivers’ licence last year, and made a road trip to Alabama at Christmas with new friends he made from Puerto Rico.

Nonetheless, loss finds ways of making its presence felt.

“I was scrolling down my LinkedIn yesterday and I saw some of my friends from uni, people in good positions, going on with their lives and working for big firms after they graduated, stuff like that. If we didn’t have this coup, we could be on the same path,” Joe said.

He toyed with the furred lining of his hoodie as he continued. “It’s fine if you don’t have big ambitions for your life, but for me, I have a lot of dreams. I want to do a lot of things. And I feel kind of stuck, like I tried so hard to reach for those points in my life and it all got smashed down in one day, and now my life is starting over here from zero.”

Days pass cycling between gratitude, frustration, resentment, and relief, along with exasperation at the limp response from the international community, including ASEAN. The Southeast Asian bloc remains split over its diplomatic response to the coup, and has been criticised for making little progress with its ‘five-point consensus’ plan.

With his humanitarian visa due to expire in July, Joe is preparing to submit a formal application for asylum. Min is still figuring out where he will be then. With travel restricted due to the pandemic, the Thai government has been granting extensions to individuals on tourist visas, but there are signs that their patience is running out. Migrants have been sent back across the border, and the visa amnesty, as it is known, is expected to end as the country opens up.

For now, he is compiling back-up plans in case his visa is not extended when it runs out in May. One option is to save up and enrol on a Thai language course, which would buy him a few months on a student visa. Another is to try for scholarships at universities in Thailand and elsewhere in the region. If neither works out, he may try to leave for Cambodia and re-enter, though there is no guarantee he’ll be allowed back in.

Whatever happens, returning to Myanmar will not be part of the plan.

For now, he is thinking in terms of weeks, not months or years. “I don’t think about my future. I’m just going to go with the flow and confront whatever happens next because I can’t imagine what it’s going to be like in the next few years. Not now.”

(The names of people interviewed for this article have been changed to protect their identities and safety.)

Sophie Chew is a freelance journalist and writer based in Singapore covering social issues, including inequality, migration, and governance.