This is the final of our five-part series, Cambodia in Quarantine, investigating the impact of the global pandemic on the four pillars of the Kingdom’s economy –garments, agriculture, construction and tourism. Sign up now to get all the stories in an e-magazine format and support independent journalism from across Southeast Asia.

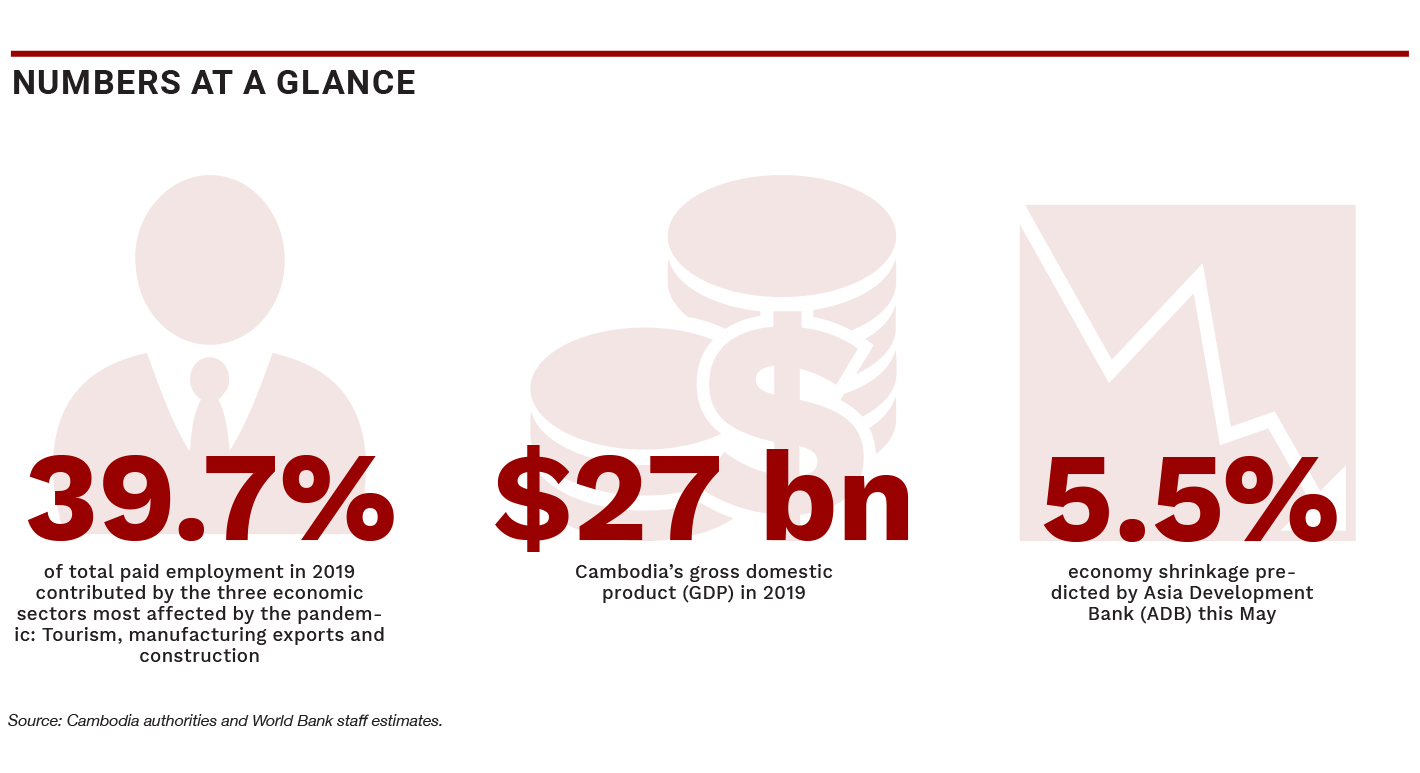

Small as it might be relative to the global powers it’s positioned between, the Cambodian economy is a lot to wrap one’s arms around. The nation of some 16 million people with a combined economic output of roughly $27 billion, has been set like so many others on a dizzying ride these past few months. To tally this quantitatively was a challenge; to put it in qualitative terms, even more so.

The Covid-19 pandemic has, to put it lightly, been the story of the year, if not the decade, with deep impacts that won’t be fully known for a long while yet. In most places, this story has coalesced around data; infections, contact tracing, worker layoffs, government stimulus spending, economic retraction and so on and so forth. Even in Cambodia, just one small slice of the global economy, the story of the pandemic’s effect on society is one that is playing out in every city, province, phum and household.

Depending on just how you want to slice it, there’s no shortage of numbers to be picked apart; depending on which you choose to look at, some very different pictures can materialise.

At the beginning of 2020, most international monetary organisations had pegged Cambodia for another year of 7%-plus gross domestic product growth. By early spring, as the bounds of the novel coronavirus were starting to be realised far from its origin in China, these predictions had fallen to a sluggish, yet still, in hindsight, optimistic pace of growth. Now, they’ve taken on various shades of dire. If the worst estimates thus far – that from the Asia Development Bank – comes to pass, Cambodia will experience an economic contraction this year of nearly 12%.

A rising tide may lift all ships, but with globalised downturn affecting virtually every paid sector, the entire spread has been severely limited

As of now, most observers are expecting a rebound in 2021. But while national economies may be on the mend, it’s unclear when the workers who build them will be made whole.

In a joint project, Phnom Penh organisations Future Forum and Angkor Research are trying to get out in front of the tidal wave of numbers shaping the pandemic as it lands on the Cambodian economy. The project began in earnest some months ago and will continue through the year to capture as much data as possible on the effects of the global economic downturn on the Cambodian people.

So far, what they’ve found is not encouraging, though it has given more weight to a growing picture of a long-simmering debt crisis now brought to a boil due to the loss of jobs and money. A recent survey conducted by Angkor Research and published last month suggests nearly one-quarter of Cambodian families had in April taken out loans to pay off other loans.

Ian Ramage, director of Ankgor Research, was quoted in the Los Angeles Times this week as saying the level of borrowing for household expenses was previously unseen in the Kingdom.

“If this trend continues, Cambodia is at risk of reversing 20 years of development and going back to being a country with a 40% poverty rate,” Ramage warned.

The current situation, paired with less ability to pay thanks to a contracting economy, is a debt-fueled house of cards built over many of the country’s most vulnerable families.

Still, to draw any conclusions about the ongoing effects of pandemic, researchers need to better understand where the country was before the novel coronavirus swept the globe.

In Cambodia, where primary data has been less accessible than in more developed economies, this has proven to be a challenge. At various points in this reporting process, we were faced with fundamental questions that spoke frankly to the scope of the economy, not to mention the scope of recent economic loss.

Some sectors are more structured than others here and keep tabs on operations to a degree that would satisfy most journalists. In others, the numbers are less forthcoming, in part reflecting the informal nature of many jobs in the Kingdom.

According to rights group Solidarity Center, as many as 80% of construction workers were employed informally as of 2018, placing them largely outside the system of official labour protections. While we have official estimates of how many construction workers there are in Cambodia, Khun Taro, programme manager at labour rights group CENTRAL, said it’s hard to actually know how inclusive these numbers are.

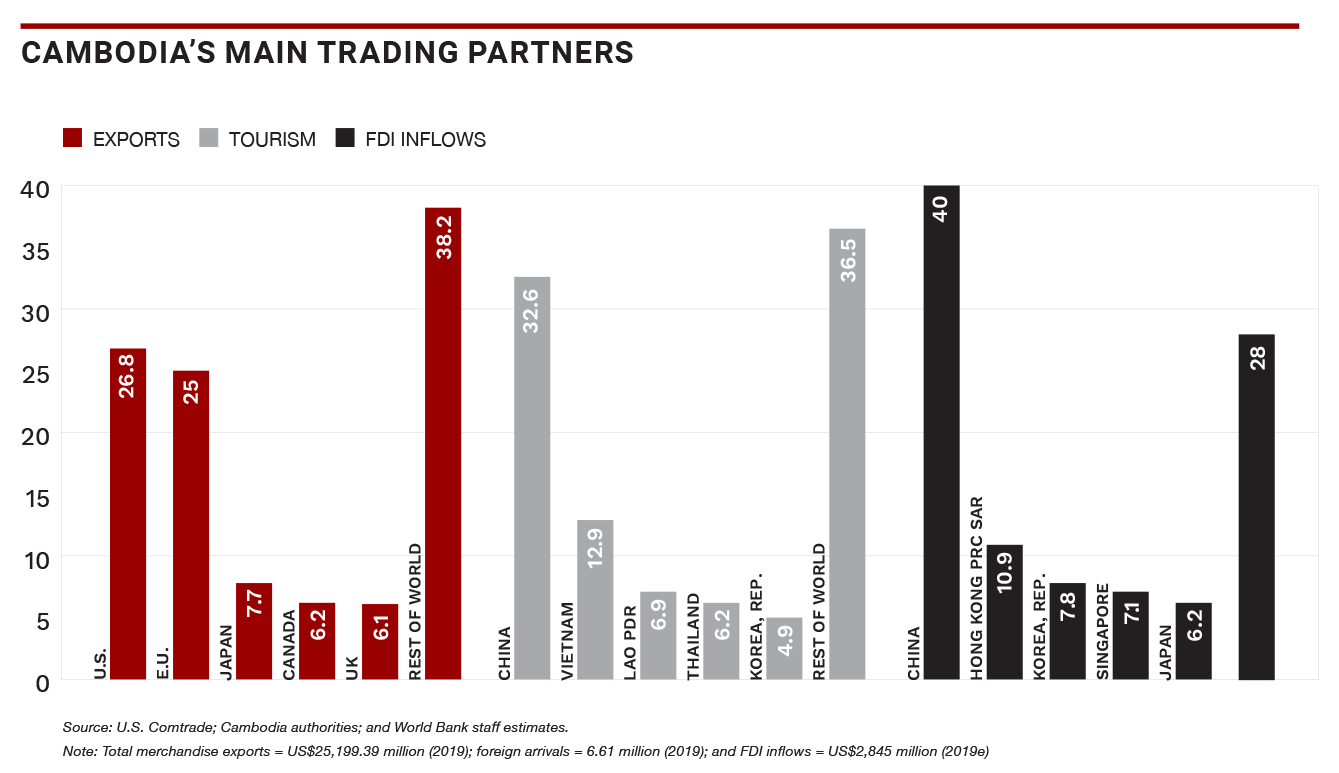

Cambodia’s informal economy has, in some ways, bred resiliency into the system. In the past, if work dried up in one sector or another, the fluidity of labour allowed workers to go where they were needed or where fortunes looked brighter. Households here may consist of multiple generations casting a wide net across multiple industries. A rising tide may lift all ships, but with globalised downturn affecting virtually every paid sector, the entire spread has been severely limited, and with it the labour mobility that so many once depended on.

Even geographic flow has been constrained. Thousands of Cambodia’s roughly one million outgoing migrant workers, who previously made money in Thailand or other countries to send home roughly $1.6 billion in remittances last year, have been forced to come home as national borders slammed shut to keep out the viral spread.

Stories are dependent on viewpoint and, for years now, the narrative on Cambodia from its boosters and backers alike has largely been one of economic triumph. According to the World Bank, the poverty rate here had fallen to 13.5% by 2014 from 53% in 2004.

That’s a triumph by any measure, but the accounting around this statistic belied the remaining precarity for those lifted from the greatest deprivation, some 4.5 million of whom remained near-poor and vulnerable to tumbling back below the line.

In its May update, the World Bank cautioned the poverty rate in Cambodia could increase by as much as 11% in households employed in key sectors like the ones covered in our series, namely those experiencing a “50 percent income loss that lasts for six months”.

Such a loss would appear to be in the realm of possibility. Indeed, for those employed in tourism, it could be even longer yet before the industry is pulled up from its current depths. Though there are plans in the works to establish a “travel bubble” with other low-Covid Asian countries to resume some cross-border movement, the Cambodian Ministry of Tourism is estimating at least five years for the recovery of incoming tourist numbers to their pre-pandemic numbers.

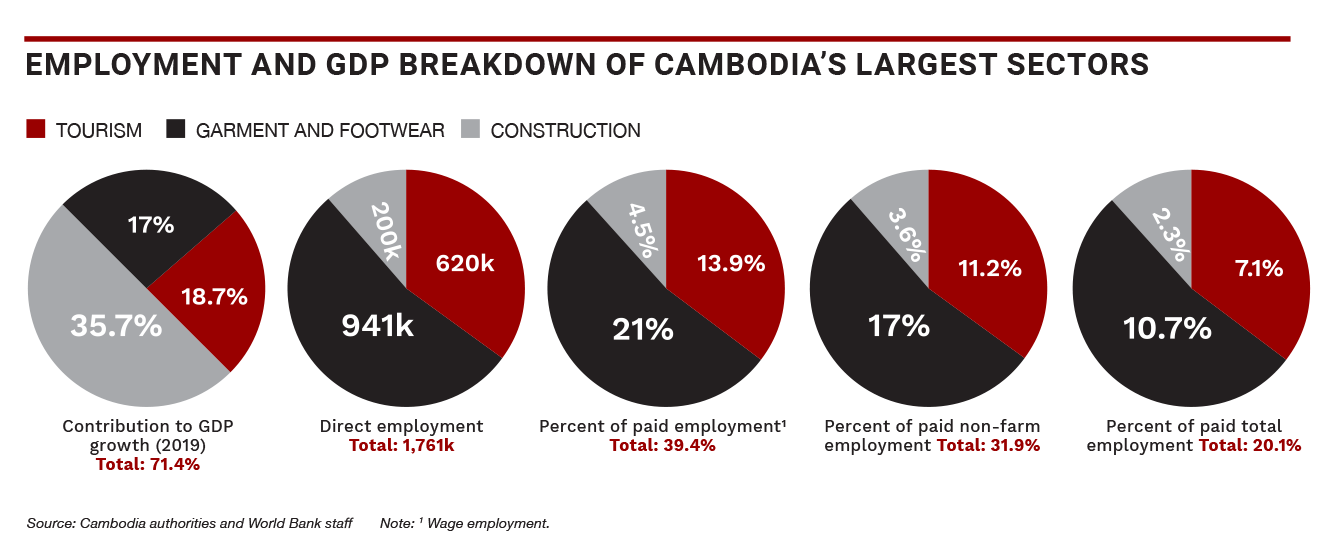

As mentioned earlier in this series, the World Bank’s analysis back in May found at least 1.76 million jobs to be at risk. The full extent of loss to the informal economy – the operators of food carts, of small shops run from the front rooms of homes, all the purveyors of goods and services who jostle and crowd to make a living – will likely be even more yet.

The flexibility of the Cambodian people has given this small but hopeful country a great deal of resiliency as it has navigated the tides of globalisation. But in the face of an unprecedented global shock that has forced many countries into a state of national quarantine, the people and their leaders will continue to be tested in ways we might not be able to imagine.

In Numbers

Now, that story has been rewritten, piece by piece and number by number. At a glance, we’ve broken it down as follows with a few key benchmarks. This Kingdom of about 16 million people in 2019 had a gross domestic product (GDP) of approximately $27 billion and, since 2015, has been classified by the World Bank as a lower-middle income country, a hard-won upgrade from its least developed status. Since then, the country had enjoyed annual GDP growth of about 7%, a level it was initially expected to maintain through 2020. That rosy projection took a sudden turn with the rise of the novel coronavirus, leading the major monetary institutions to revise their outlook. Today, Cambodia is expected to have its worst economic year in decades.