This is the first of our five-part series, Cambodia in Quarantine, investigating the impact of the global pandemic on the four pillars of the Kingdom’s economy – garments, agriculture, construction and tourism. A pillar will be published each day on our website, while paying Globe members will receive early access to the full report in a special e-magazine. Sign up now to get all the stories today and support independent journalism from across Southeast Asia.

Back when he was working at the garment factory, Seurn Chhim had to wake up around 4am to make it on time for the start of his shift.

His morning routine was simple. First, as his two children slept, he prepared rice and packed his lunch for later at the factory. After making the food, Chhim took a shower, got dressed and, along with his wife, Sem Sovann, made the brief walk to the point where an open-backed truck would pick them up, jostling with crowds of men and women on the route to Gladpeer factory in Por Sen Chey, Phnom Penh. The ride took about nearly an hour to bump the crew to work before the 7am starting-time.

Now, months unemployed and waiting at home for production to begin again at his now-shuttered factory, Chhim looks back on those rides as a cherished time of day.

“We share the talk in the truck together, and joke around in the truck along the way to the factory,” he said, sitting at home in Kandal. “I miss it.”

Seurn Chhim, 40, has been out of work since 22 April, when the Gladpeer factory suspended operations, declaring bankruptcy as a result of a lack of orders due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Both he and his wife are now among the approximately 130,000 workers in Cambodia’s garment and footwear industry who have lost their jobs due to the global economic downturn.

Before the onset of the novel coronavirus, the industry, when counting footwear and travel goods, employed close to a million Cambodians who produced about 74% of their nation’s exported merchandise.

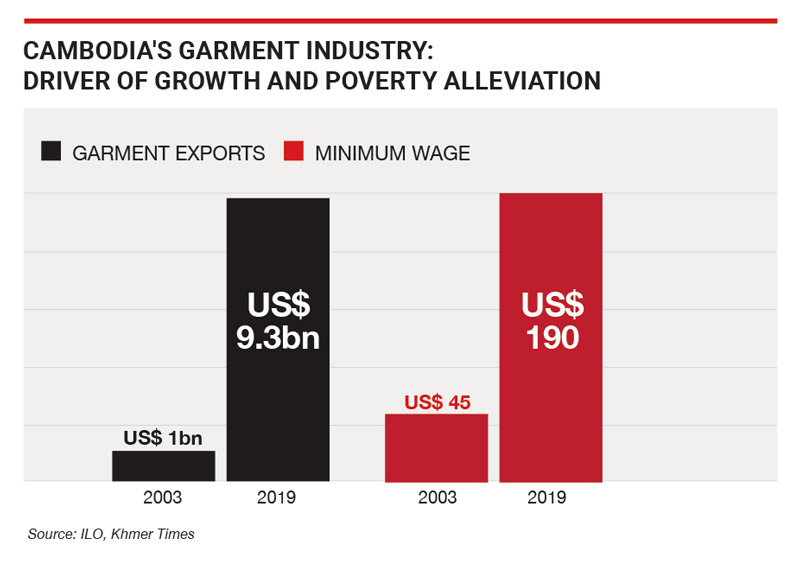

According to local media, Cambodia exported $9.3 billion in garment products, footwear and travel goods in 2019, an increase of 11% from the year prior, says the Ministry of Industry, Science, Technology, and Innovation. Looking further back, garments, footwear and textiles amounted to less than $1 billion in exports in the year 2000, according to the International Labour Organisation.

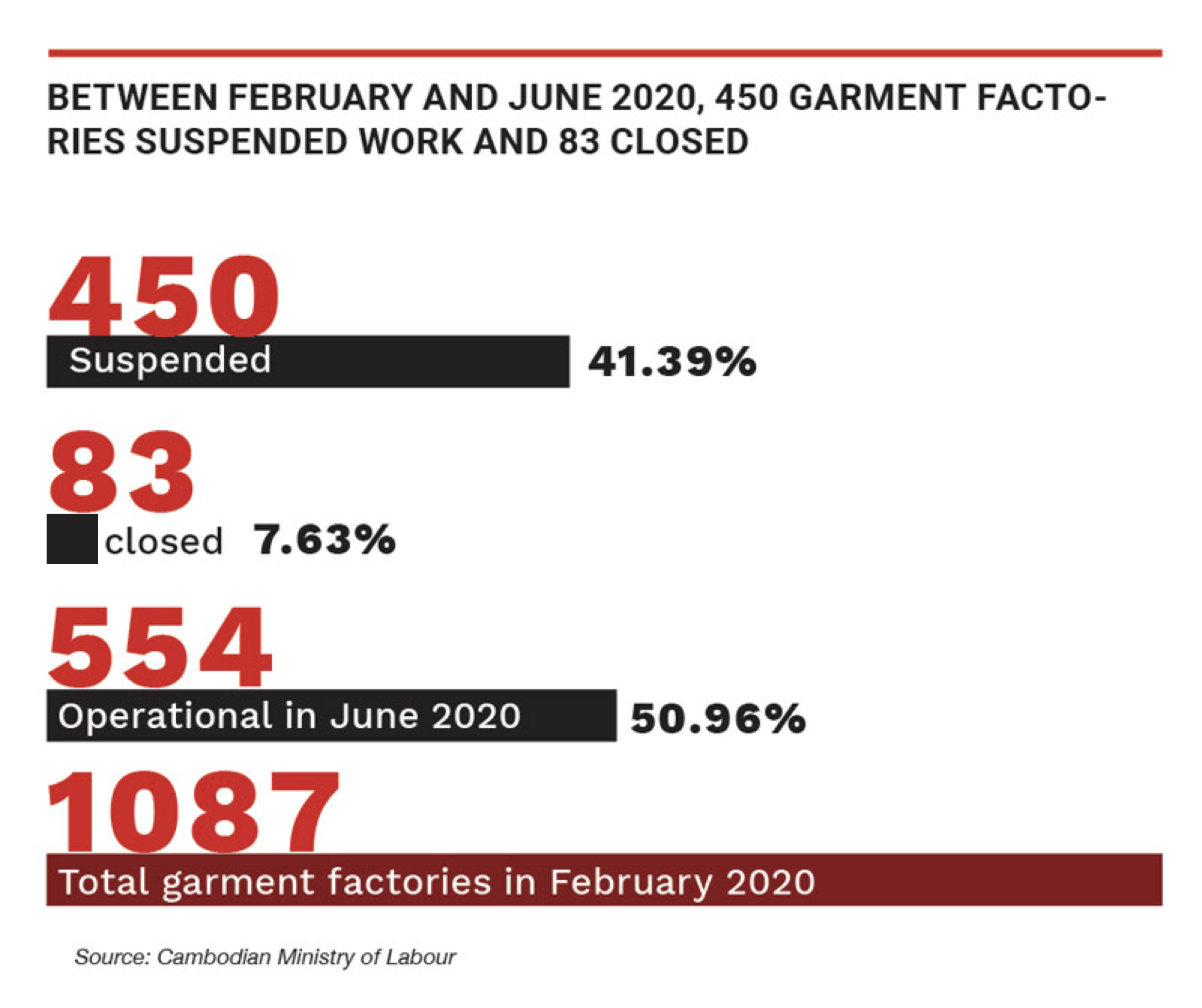

Reporting from government statistics, the World Bank said that as of February this year, the export garment, footwear, and travel goods industry consisted of 1,087 factories and employed 941,000 workers, representing 21% of paid labour and 10.7% of total employment in the Kingdom.

The Ministry of Labour reports that, as of June this year, 450 factories had suspended production while 83 factories officially closed.

So far this year, according to reporting from mid-July, Cambodia’s total garment exports were worth almost $3.8 billion. Despite the massive decline in demand from overseas, that’s a monetary decline of just about 5.4% from the same point last year. Even still, the decline in exports is a significant loss for an industry that has consistently enjoyed exponential growth in recent years, and has resulted in the evaporation of thousands of manufacturing jobs.

The sociopolitical effects of the loss of income and export wealth is already rippling out into Cambodian society.

Ath Thun is the president of the Coalition of Cambodia Apparel Workers trade union, representing around 110,000 workers. He said that, as the industry has contracted throughout the year, many laid-off workers trickled back to their provinces. Others have remained protesting in front of their factories, holding out for owed wages, while others still have tried to find new jobs in the remaining factories.

“I think only 15% could find new jobs in factories,” he estimated. “That is mainly those who are very experienced … But for those who are just ordinary workers, it’s more difficult.”

As factories officially suspended operations, around 265 production centres closed their lines, affecting an estimated 130,000 jobs. But Thun is skeptical and suspects it’s closer to 200,000. With so much economic uncertainty, he added, workers are increasingly turning to loans to survive.

“Sometimes when I meet with workers at their factories they tell us they’ve taken loans from factories, microfinance companies, and informal loans. We could say that 70% of them are on a loan,” he said. “When they returned home, they had to live in a situation where they did not have regular income. They have to face spending on food and loans that they owed from microfinance or banks.”

Without a regular factory income, Chhim said, his family’s living conditions have been stretched to their limit. He’d been working at the factory for about 12 years, earning some $300 per month, a fair bit more than the industry’s minimum wage of $190. But in the third week of April, a dire month for the global economy, administrative staff at the Gladpeer factory, which produces H&M-branded clothes for Western consumers, announced that work would come to an end. They calculated his pay and his last working day was 23 April.

Suspension, that’s a precursor, it’s a hibernation – it’s hibernation with a cost

Ken Loo, GMAC

The economic shocks of Covid-19 have rocked factories across the Kingdom. First, the virus hit the supply side of the equation with China, a key player that provides Cambodia with raw materials that go into the making of clothes, the first to shutter when the virus picked up in January.

Demand from the West was next, as economies hit the pandemic brick wall. With nobody to sell to, the emperor has been left without a stitch to cover his balance sheet.

The impact of the virus is only exacerbated by the withdrawal of the EU’s Everything but Arms (EBA) preferential trade agreement, a decision first announced in February and set to come into effect on August 12. The bloc cited the Kingdom’s worsening civil and human rights situation in its reasoning for the move.

EBA has provided the Kingdom with duty-free exports to the bloc since 2001, allowing Cambodia to flourish as a favourable, low-cost hub for production. Now, with tariffs set to return, many factories have already begun the process of relocating to other countries.

Ken Loo, Secretary General of the Garment Manufacturers of Cambodia, said this combination of factors means local manufacturers are left in the mire of uncertainty. Short of closing their doors for good, many local producers have opted instead to suspend their operations, some indefinitely, while waiting for orders to materialise.

He added that suspensions in recent months were planned with the government to buy some time for factories that would have otherwise closed outright.

“We’ve had some closures, but I don’t know exact numbers,” Loo said. “Suspension, that’s a precursor, it’s a hibernation – it’s hibernation with a cost.”

However, those waiting for dark clouds to lift have been given little reassurance. According to a recent survey of GMAC members, only 35% of respondents reported having sufficient orders until the end of the year. A further 40% said they had “some orders, but insufficient” and about 25% reported having no orders, Loo said, “probably until the end of the year”.

Businessman Maha Roof was stuck in the doldrums of “some orders, but insufficient” until he ultimately decided to close production across the nine factories he ran.

Of Pakistani and Sri Lankan roots, he’d moved to Phnom Penh more than a decade ago as part of his career among a network of pan-Asian businessmen producing and exporting a variety of goods. Up until the shock of pandemic, he said, business was good.

“I’ve had 10 years making money here,” he said. “Now, in six months, it’s gone.”

Roof said the cluster of factories he helped oversee about 80 kilometres south of Phnom Penh had formerly employed about 9,000 people. The goods made there were mainly sent to global fashion retailer Zara and could pull in as much as $1.5 million in profit each year. The cotton was originally from India and Pakistan, the thread from Bangladesh, the textiles from China and the various accessory details from Taiwan, South Korea and elsewhere. The finished goods, mostly dresses and blouses, were sold in the UK and Canada.

As with others, Roof’s problems first began on the supply side, when textiles from China were interrupted.

“If I can’t get the material, I can’t start production,” he said, putting up his hands in exacerbation.

While he waited for supplies to come through, costs kept stacking up – about $25,000 each day with no revenue to offset the bleeding. Last year, he and his business partners had begun the process of investing major capital into an expansion of their production capacity. Now, he said, they’ve been forced to sell off four of the factories, while the remaining five have been suspended since May.

He said his management group used the proceeds of the factory sales to pay out three months of salaries to the line workers and, while they hope to reopen one of their remaining factories this fall, the future will ultimately depend on a resumption of demand. For now, he said his regular buyers are “in confusion” as to their own ability to sell.

“It was a pain to close the factories, and I’m not just talking about money,” Roof said, describing the process of breaking the news not only to labourers, but also to the vendors that operated carts that served them. “My staff, OK, we have capacity to not work for one year, a few years, but the labour, they cannot. So the next target is to get them back to work.”

Appealing to an Islamic sense of charity, he says he’s tried to provide some food aid and find job placements for workers who have come to him for help. One possible landing point is in the restaurant he’s creating, Maha Bistro, as well the factory he hopes to reopen this fall.

For producers like Roof, suspensions bring their costs, but hibernation remains the best option for many who hope to reawaken at the first sign of virus-free spring. In the meantime, Loo said the workers themselves are part of a stipend programme where they receive about $30 from GMAC itself and an additional $40 from the government.

As far as any trends for survival prospects for producers, Loo said the industry is looking at “across the board” instability that affects companies large and small.

“We have very big factories, like shoe factories with 10,000 workers, that have to be suspended,” he said. “[But] the general trend is that smaller factories would find it harder to survive because, intrinsically, financially, they’re in worse off position than bigger factories.

Workers like Seurn Chhim, who lack the capital for an entrepreneurial pivot, are left at the mercy of this globalised system of supply and demand. To make matters worse, he’s skeptical of the nature of the factory’s closure, as well as the calculations dividing up final paychecks.

“The factory closed because of Covid-19, no-one ordered, so they have to close,” Chhim said. “That is what they told us. However, I think it’s also because they wanted to get rid of people who had been working there for a long [time].”

“I got paid only $1050 for the last payment, however I was supposed to get more than $2000 when the factory closed.”

Chhim’s wife, Sem Sovann, 38, had worked for the same factory in the sewing section since she was 21. Sovann recently got her last payment of $1,286. With overtime, she used to earn around $300 per month.

“As the factory closed so suddenly, I did not know what to do,” she said, lifting her two-year-old daughter, her youngest child, onto her lap.

Still, Sovann was luckier than her husband. She got a job at a different factory after just two weeks with the help of her old team leader. Even with her husband out of work, the sheer volume of production happening at her new workplace made her feel hopeful about the prospects she could, at least, keep this new position.

“I think we may not have a problem,” she said, describing the amount of clothes being sent out for export each week. “It is a very big factory, so I am not so worried it will close.”

Before we had two people earning so we were able to spend around $5 per day for three meals. Now we have to reduce it to $2.50

Sem Sovann

Before, the couple had been able to earn a combined $650 per month, saving around $100-150 per month. With that kind of income, the couple felt confident enough in 2014 to take out a $7,200 loan from the bank in order to build a house.

“At this factory I have to do an over-time job until 8pm. I am working alone, so I have to earn alone as we need more money,” she said. “Sometimes when I arrive home, we get frustrated because I am very tired and he is tired as he has to do all the chores.”

With Sovann away at work, Chhim has taken over the domestic duties. He spends the day caring for the children and the house, as well as tending the family’s half-hectare rice farm. The plot of land has been a welcome addition this year. While, in the past, they could earn about $100 per year selling rice, this year they’ve put the grain directly towards their own consumption.

The family, however, needs the money that only cash labour can provide.

“Before we had two people earning so we were able to spend around $5 per day for three meals. Now we have to reduce it to $2.50. I have to be strict with my kids; before we gave them a dollar per day for snacks, but now we can’t do that because we don’t have an income.”

Sovann and Chhim are not keen on jobs in different fields, and besides, with the entirety of the Cambodian economy hard hit, garment and footwear factory workers have limited options to pivot.

“We could do farming, but we will not have our regular salary … If we don’t have regular income it will affect our family, it will affect the children’s studies,” she said. “I don’t know where to go for any new skills, we’re just going to let it be and stay at home if there is no factory.”

Next the Globe will be looking at the impact of the pandemic on Cambodia’s agriculture sector.