As Myanmar’s security forces continue their crackdown on the nation’s Muslim Rohingya minority, foreign-born fighter Ata Ullah is leading a group of insurgents in guerrilla warfare

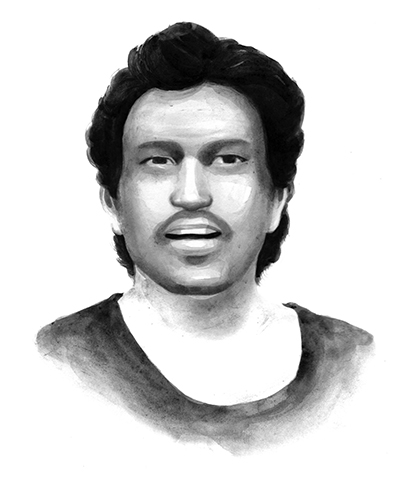

Filled with a restless energy, the man in black paces back and forth before a shaky video camera, a quivering hand raised to the sky as he spits rapid-fire Bengali into the lens.

“We are not terrorists. We came out to restore our rights. God willing, we will take back our rights from the brutal and unjust government.” Pulling the cameraman over, he stabs a finger at a clump of bloodied boys sprawled across makeshift tarpaulins, allegedly maimed by mortar fire from government security forces. “These are civilians, not terrorists.”

Commonly known as Ata Ullah, the man in the video is believed to be the spokesperson and leader of the ground troops of the Harakah al-Yaqin insurgency in Myanmar’s Rakhine State. Variously translated as ‘Faith Movement’ or ‘the Movement of Certainty’, the group thrust itself into the international media spotlight after claiming responsibility for the raids on Myanmar border police in October. The attacks, which killed nine border officials in three coordinated assaults on government outposts, triggered a violent military crackdown that has driven tens of thousands of Rohingya across the border into Bangladesh and reduced whole villages to

smouldering ruins.

Although born in Karachi, Pakistan, to a Rohingya father who had previously fled the violence of his homeland, Ullah – also known as Ameer Abu Amar, Abu Amar Jununi and Hafiz Tohar – grew up in the holy city of Mecca in Saudi Arabia, where he was educated at an Islamic religious school. A report on the rise of Harakah al-Yaqin released in December by the International Crisis Group (ICG) described a man incensed at the suffering of his fellow Rohingya in a homeland he had never known.

“He disappeared from Saudi Arabia in 2012 shortly after violence erupted in Rakhine State,” the report stated. “Though not confirmed, there are indications he went to Pakistan, and possibly elsewhere, and that he received practical training in modern guerrilla warfare.”

Muhammad Haziq Bin Jani, a research analyst at the International Centre for Political Violence and Terrorism Research and one of the authors of Myanmar’s Rohingya Conflict: Foreign Jihadi Brewing, said Ullah’s rejection of his affluent Middle Eastern lifestyle to pursue the fight against Myanmar’s military was a tale typical of Harakah al-Yaqin’s foreign-born fighters.

“Certainly the ideology that was resurrected by the Saudis and the jihadist groups over time has basically been used [by these fighters] to imagine that they could be the heroes of the Rohingya communities,” he said.

By sacrificing the comfort and security of their old lives in Saudi Arabia to fight against the government’s security forces, they have demonstrated an apparent willingness to bleed for their people – and, in return, received at least a measure of temporary support from sections of the increasingly desperate Rohingya community. Those who refuse to support their brutal methods, or dare report on their activities to government forces, are often found with their throats slashed as a warning to any who would dare question the righteousness of their campaign, according to the ICG report.

Nehginpao Kipgen, executive director of the Centre for Southeast Asian Studies at India’s Jindal School of International Affairs, suggested that the return of foreign-born Rohingya fighters to their ravaged homeland could have been prompted by widespread media reports of Rohingya being tortured, raped and brutalised by government security forces.

“There may be a couple of reasons,” he said. “The first is due to the continued suffering of the Rohingya as a community, especially since the aftermath of the 2012 violent conflict. Another possibility is due to the strong interest from the international community in the plight of the Rohingya. In either case, the media has played an important role.”