Faced with a choice between staid titles by established authors and more salacious fare, many Malaysians are picking the latter

By Marco Ferrarese

If you go down to Malaysia today, you might be in for a big surprise: flesh-eating zombies, teenage drug runners, cannibal condoms from outer space, Jemaah Islamiah-affiliated terrorists on the hunt for runaway Thai prostitutes, glue-sniffing motorcycle gangs, shifty immigrant workers, corrupt officials, incestuous imams and all manner of ghostly apparitions are on the loose. No cause for alarm though – we’re in the weird and wild world of pulp publications.

Giving Malaysia a bad name is all in a day’s work for 42-year-old publisher and film director Amir Muhammad. His signature series of controversial pulp novels and short-story collections, KL Noir, are published under imprints Fixi (Malay language) and Novo (English language) and have already kicked other mainstream Malaysian authors off the top of the country’s bestseller lists, collecting hundreds of rave reviews on Good Reads along the way. Two titles – heist story Pecah and living dead apocalypse yarn Zombijaya/KL Zombi – have even been made into feature films. According to Muhammad, the secret of Fixi’s success – sporting average sales of 8,000 copies for Fixi, compared to 3,000 for Novo titles – lies in the fact that “pulp fiction is fast and furious” to the Malaysian reader. This could be seen as encouraging in a nation that, according to its minister of education, Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin, doesn’t read enough books.

Fixi has been spicing up bookstore shelves since 2011 and won itself a dedicated readership by publishing a diverse array of compelling urban crime, horror, mystery and science fiction. Written by a crew of young Malaysian and expatriate novelists, Fixi’s books have defied conservative stereotypes by using Malaysia as an ideal setting for fast-paced, dark-edged pulp stories. Most importantly, Fixi has showed how young Muslim writers embrace dark, urban thrills, rather than follow the tradition of nostalgic glorification of colonial-era Malaya, as more internationally established Malaysian authors do.

Brian Gomez, author of one of Novo’s most interesting titles, Devil’s Place – an amusing rollercoaster ride into the shady world of Malaysian political corruption – says that “before Fixi, Malaysia only had romance and the kind of novels with a moral. If you wanted crime fiction, you’d have to buy a foreign book.”

But what about Malaysia’s repressive censorship, always ready to mutilate any cultural product if it doesn’t comply with the rules of Islam? How has Fixi escaped the scissors of Jakim, the dreaded National Department for Islamic Development? Truth be told, Muhammad doesn’t seem too bothered about censors. “There have been some campaigns against Fixi, but they weren’t led by conservative groups,” he says. “We were instead targeted by some of the bigger publishers once they saw a decline in their sales.”

Sharon Bakar, a British editor and creative-writing teacher based in Kuala Lumpur, says that a valid reason for Fixi’s popularity and unsullied freedom of expression is explained by the poor reading habits of Malaysians and their ostracism of English-language books. On top of that, Bakar says, “once a book receives a formal complaint from the public, it normally takes Jakim about a year to actually clear it off the shelves, granting it plenty of time to continue making waves”. On the other hand, when censors seize books, they unknowingly help boost sales. This happened in 2010 with Body2Body: a Malaysian Queer Anthology, an LGBT short story collection courageously published by Muhammad’s former imprint, Matahari Books. Obviously, Fixi’s main man is no novice when it comes to tickling the belly of the censorship dragon.

“Censorship in Malaysia, as in any country, is a way to shape or limit people’s thoughts on certain topics. Fixi is offering an important alternative to other publishers who self-censor as a rule,” says Kris Williamson, a Florida native who published his debut novel, Son Complex, through Novo. Williamson’s coming-of-age tale tells centres on a young American man who travels to Kuala Lumpur to find his father and shed light on his mother’s past, and ends up having his world turned upside down.

“When I write, I take advantage of my outsider-insider position,” explains Williamson. “It’s a perspective that few have in Malaysia. I like to observe people: this always gives me a great range of topics to write about.”

Besides censors, another challenge is the aversion of mainstream corporate bookstore chains: some refused to stock Fixi’s books because they outsold their own. Regardless, Muhammad uses efficient forms of street-based self-promotion and distribution that have helped his company bypass the efforts of Malaysia’s book-selling giants to stymie him. “On any given week, Fixi will participate in several events, from campus meetings to car boot sales outside of burger restaurants,” he says. “No other bigger publisher is willing to get their hands dirty this way.”

Marc De Faoite, an Irish writer and yoga trainer based in Langkawi, has recently published his debut short-story collection, Tropical Madness, on Novo. His stories describe “the elephants in the room that the majority of Malaysian and Malaysia-based writers seem intent on avoiding”, he explains. De Faoite has a clear idea of the reasons for Fixi’s success. “It’s the literary equivalent of fast food. Even if younger readers know they should eat their cultural greens and read more serious and conventional Malaysian authors such as Tan Twan Eng, Tash Aw or Preeta Samarasan, they prefer books that are perhaps less nutritious from a literary point of view, but that are tasty and cheap.”

One important reason for the titles’ popularity could be their price – Fixi titles sell for 20 Malaysian ringgit (about $6), whereas most imported books cost more than double that amount.

Fixi is definitely on a roll, and if giving a voice to a feisty team of local writers wasn’t enough, in January the imprint launched Malay translations of revered authors Stephen King and Neil Gaiman. This is certainly no mean feat for an independent Southeast Asian publisher.

Despite a few critical voices saying the originality and quality of Fixi’s books might not be up to international standards, Muhammad has other ideas. “It’s the same as for Malaysian filmmaking – if we were to ban all amateur works, there would be no cinema left in Malaysia.”

Indeed, if the work of amateurs has been able to revive the local publishing industry and satisfy the appetites of an increasing number of young Malaysians, let these greenhorn writers take centre stage.

***

Five of Malaysia’s best:

Pecah (2011)

by Khairulnizam Bakeri

A racy heist novel set in the Kuala Lumpur suburb of Shah Alam, this was the first Fixi novel to be made into a feature film. Unfortunately, its elaborate flashback structure was not reproduced for budget reasons.

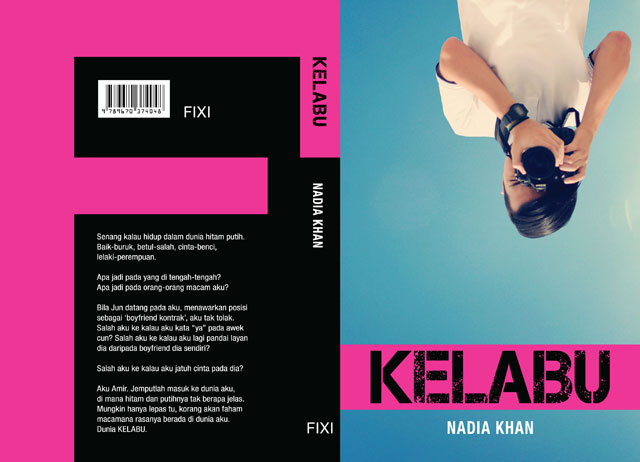

Kelabu

(2011) by Nadia Khan

Fixi’s all-time bestselling title isn’t a proper pulp novel – it’s a first-person account of a love story spiced up by elements of (trans)gender and sexuality, uncommonly narrated by a Malay female writer.

Asrama (2013) by Muhammad Fatrim

This ghost story set in the dormitory of a Malaysian girls’ school gained much positive feedback from teenage girls – who had a ball reading it in their dorms.

KL Zombie (2011) by Adib Zaini

The world of a typical Malay slacker gets turned upside down when Kuala Lumpur is transformed into a zombie-infested concrete grave. An interesting Malaysian take on the zombie genre, it has also been made into a movie

starring Zizan Raja Lawak.

Devil’s Place (2012) by Brian Gomez

What happens when a terrorist kills your three best friends at your bachelor party and you’re forced to run away with a bag full of dirty money accompanied by a Thai prostitute? One of Fixi’s most interesting English-language titles, that’s what.

Keep reading:

“Art is life” – Street artists are colouring the streets of George Town, breathing new life into the city’s heritage quarter