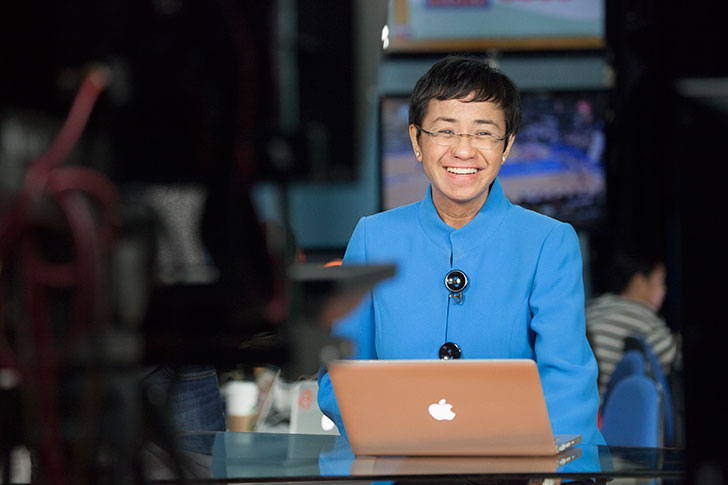

Maria Ressa, co-founder and CEO of the Philippines-based news website Rappler, is changing Southeast Asia’s media industry for a digital age

Journalism in the Philippines is often seen as a dismal pursuit. Following a short “golden age” that followed the country’s independence, the profession as a bulwark of democracy ceased to exist under the Ferdinand Marcos regime, which imposed martial law and heavy censorship.

Even today, many Filipino journalists are subsumed and consumed by a pervasive sense of irrelevance under social media’s shadow. They are often poorly paid and there are constant murmurs of corruption among their ranks. Since 1992, 77 Filipino journalists have been killed for various reasons.

executive editor of trailblazing

social news website, Rappler

But then, there is Rappler and Maria Ressa. Launched in the beginning of 2012, Rappler – a portmanteau of the words ‘rap’ and ‘ripple’ – is a social news website independently financed by four groups of investors, including Ressa.

Petite and engaging, with a silken speaking voice, smoothed to newsreader perfection, she has more than 25 years of journalism under her belt, and today serves as Rappler’s president, CEO and executive editor. According to Ressa, now three years into business, [the website] is changing the face of Filipino journalism.

“The idea was, I felt like people in power, either people or companies, here in the Philippines, in particular, were born into it. Oligarchic families who have power, economically and politically,” she says, emerging from a conference room at the rappler.com office – a modest affair with a splendid view of nearby high rises – in Ortigas, metro Manila.

“I always felt there was a zeitgeist we could tap into. There’s a need for transparency, accountability and consistency,” she adds. “We have no vested interests. We made a point of not being backed by any major power interest.”

Yet to understand the roots of Rappler, it is necessary to understand Ressa herself.

Shortly after martial law was declared in the Philippines in 1972, Ressa’s family migrated to the US. Like so many Filipinos who have reinvented themselves on foreign soil, Ressa flourished in her adopted country, graduating from Princeton university, ready for a bright future. But this future was not to take place in America.

“In 1986 I came home [to the Philippines] in search of my roots,” she says. This is how she fell into journalism. “I had a one-year Fulbright scholarship. It was an exciting, glorious time. I wrote a play, my thesis for an independent major. I came in for political theatre. But political theatre here was very agitprop and very personalistic. It didn’t satisfy me.”

Disappointed by the theatre crowd, TV beckoned to the young Ressa. She became an investigative reporter, a researcher, foreign correspondent, and ultimately the senior vice-president of a major TV station.

Between 1987 and 1995 she was CNN’s bureau chief in Manila, before moving to Jakarta for CNN between 1995 and 2005. In 2005, she took the helm of ABS-CBN News and Current Affairs, for six years determining strategic direction and managing more than 1,000 journalists for the largest multi-platform news operation in the Philippines.

“My job then was to make it more efficient and streamline its operations. I got an industrial engineer to shadow my key people for a month,” she recalls.

As a seasoned war correspondent, Ressa is also known for her writings about terrorism. Her books include Seeds of Terror (2003) and From Bin Laden to Facebook (2011), the latter written in a small Singapore flat. Both books discuss the spread of violent extremism in Southeast Asia.

But 2011 was the crucial year when Ressa pivoted away from network TV to focus on developing Rappler.

“In that year many of my colleagues at ABS-CBN resigned. I told them, let’s try something different. Create something new that’s right for our time,” Ressa says.

Helping her out were veteran journalists Glenda M. Gloria and Marites Vitug, two uncompromising trailblazers in no-nonsense reporting.

“Our advantage is we’re old enough to understand the old world and young enough to see the possibilities of the new one,” she says. “When I was in CNN our little team of four people were prototyping. We were always the one to test anything new for CNN. Then when I went to ABS I pushed social media.”

“It took me six months [in ABS-CBN] to push for reporters to use Twitter. It’s very hard for a large media organisation to move fast; the very thing that made it successful is holding it back,” she added.

Once the decision to start a new news organisation was made, Ressa and her team moved quickly.

“The principle was it’s faster to run your own organisation. You’re not part of a huge thing with so many vested interests. We were like-minded. We decided we were going to hire the smartest 20-something digital natives we could find,” she recalls. “We created it in about six months.”

Today, Rappler’s headquarters is neither a cubicle-farm nor a stuffy studio-cum-office. Its staffers and interns attired in business casual are crowded in even rows, typing away at glowing MacBooks. They’re all young, millenials between 20 and 23, and that is how Ressa likes it. Plasma screens adorn the walls streaming news and basketball. Ressa and Gloria have their own shared office, minimalist and uncluttered, occupied by three staffers fretting over deadlines.

“We don’t have hierarchy,” Ressa says about the office culture. “It’s such a flat organisation. Everyone sees what everyone is doing.”

In Rappler, the women also outnumber the men. It is a haven for female journalists whose coverage runs a fine-tooth comb across a fractured and colourful nation. To be fair, the heavy presence of women in a news organisation is not extraordinary. A salient feature of modern journalism in the Philippines is the female writers, reporters, broadcasters, producers, and executives who are shaping and reshaping the profession.

One of the country’s leading newspapers, the Philippine Daily Inquirer, was founded by Eugenia Apostol and Betty Go-Belmonte, both pioneering journalists and publishers. Go-Belmonte would then launch another newspaper, the Philippine Star. Ressa’s former employer, TV network ABS-CBN, is led by CEO Charo Santos-Concio, a soap actress.

Ressa herself owes a debt of gratitude to Cheche Lazaro, whose Probe series established investigative TV documentaries as a viable genre. Newly transplanted from the US in the 1980s, Ressa lived in the Lazaro household for two years before finding a place of her own in Manila.

A little more than a year after it launched, Rappler finalised its management, which currently includes chairman Manny Ayala, an old colleague from Ressa’s days in production and filmmaking. Ressa herself is president, CEO, and executive editor. Gloria is the vice-president and managing editor. Below them is an intricate assemblage of staffers.

Rappler’s mystique stems from Ressa being amazed by what Twitter was doing to the staid newstream during the naughties. It was addictive, mystifying, tearing at her bookish laser focus. She wondered aloud about how it affected a person’s neural circuitry.

“What I noticed was that the more I engaged on the Internet, the less I engaged in my own thoughts,” she says. “When your Blackberry buzzes or your Twitter tweets, it pulls your mind from whatever it’s doing. It also gives you a chemical buzz from dopamine, which apparently is highly addictive. We’ve become dopamine junkies!”

According to Ressa, the advent of social media has dramatically changed the news industry.

“Today, breaking news will come from someone in a neighbourhood or in the streets. The traditional news people will come in afterwards,” she says. “The other day the LRT [transport system] stopped. The passengers had to go down and walk [and] there wasn’t a journalist among them. Or the collapse of the ceiling in Cebu in the Ayala cinema… The breaking news now is from the people who live there. Then the journalists come in and provide context it for it and tease it into a larger story.”

Another factor that immediately separated Rappler from its competitors was its pioneering use of a ‘mood meter,’ a basic but effective feature on all online articles that gauges the reader’s feelings toward content.

“So many studies show that 80% of the decisions people make in their lives are based on what they feel, on their emotions,” Ressa says. “It’s true in real life. The internet only magnifies it.”

[manual_related_posts]

Apparently, the same dynamics behind attracting share-worthy content is a sweet deal for advertisers, and this is Rappler’s secret weapon.

Ressa pulls out her laptop, a weathered MacBook, and reveals reach-social.com, or Reach for short. It is also run by Ressa and her Rappler colleagues.

Reach provides an interactive map for tracking social media influencers and their connections in real-time. “We’re using the same technology that was used to map the Arab Spring and then translate it in a way that can be used for digital marketing,” Ressa explains. “This is how we monetise.”

Ressa credits the treasurer and marketing head Carla Yap-Sy Su for overseeing Rappler’s bottom line. And yes, there is a bottom line. Corporate advertisers can pay for sponsored posts and banners. But with Reach, Rappler can go farther without selling out to ‘the Man’ and his vested interests.

“I think we have the business model that this entire news industry is looking for,” she admits. “For traditional media the growth curve is linear. Right now in the US, it’s declining. But if you combine traditional media with tech, the growth curve is phenomenal,” she adds. “We’re growing by multiples of a hundred – compared to the double digit growth on TV.”

Rappler is primed for a new market, Indonesia, with a mix of English and Bahasa content. It’s a development that recalls Ressa’s former life as a correspondent in Jakarta for several years.

“That’s why travelling and physically moving house every now and then is essential,” Ressa once reflected on her website in 2011. “Too often, as we get older, we stop really looking, stop really listening, stop living in the moment.”