“Growing up, whenever I felt a fever coming, I was always advised to drink the ‘rhino water’,” says international legal expert Shirleen Chin from her office in the Hague, a long way from her native Malaysia. She knows the strength of belief in such products, rooted in traditional Chinese medicine, thousands of years old.

As far back as the fourth century, rhino horn was viewed as a near-mythic luxury item which was the essence of such concoctions, just like the cocaine in every bottle of Coca-Cola until 1903.

Similarly, “rhino water” is named after a former ingredient. It’s imbibed as a restorative “which has an alkaline Ph level that it works to cool the body down,” Chin explains. “It does not contain parts of rhino.”

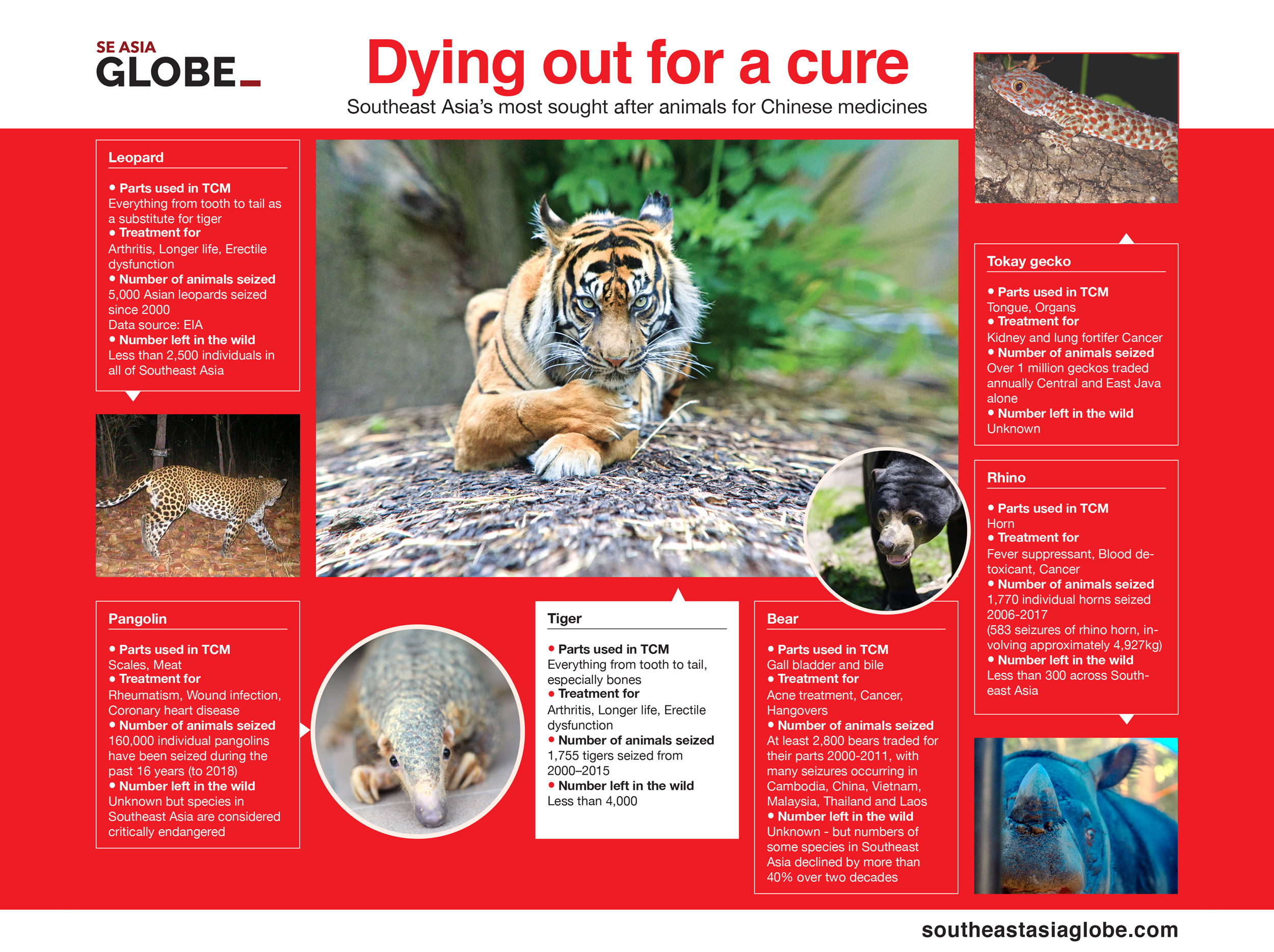

For many, the faith in such remedies is unshakeable, and every once in a while, a “miracle” comes along to affirm it. In the mid-2000s, rumour had it that rhino horn had cured a former Vietnamese politician of cancer. Rhino populations were devastated as demand for its powdered horn soared, wiping out three species. Vietnam’s last rhino came crashing down in 2011 – found with a bullet in its leg and a septic wound where its horn once was.

Rhino horn is largely made of keratin like our hair and nails. There is zero scientific evidence for its effect on cancer.

It is very clear that today the primary driver of illegal wildlife trade is Traditional Asian Medicine

Dr. John Goodrich, Panthera

The former politician was never named, and some suspect the rumour was started by rhino horn magnates who wanted to see the price of their deadly stock increase. Gram for gram, rhino horn is now worth more than gold. Southeast Asia’s jungles were once home to thousands upon thousands of rhinos. Now scarcely more than 100 remain.

“It is very clear that today the primary driver of illegal wildlife trade is Traditional Asian Medicine,” says Dr. John Goodrich, chief scientist and tiger programme senior director at global wildcat conservation organisation Panthera. “And there is no evidence that this is likely to abate in the near future.”

Nowhere is this threat greater than in Southeast Asia, a region known for its Noah’s Ark of biodiversity – and lax enforcement of laws to stop those who plunder it.

It was belief as much as a poacher’s gun that killed the rhino. Today the threat facing rhinos, tigers and other animals across Southeast Asia is bigger than ever – originating from the ambitions of a non-believer: Mao Zedong.

Old wine in new bottles

Mao was actually not a fan of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), telling his western-trained personal physician Li Zhisui, “I personally do not believe in it. I don’t take Chinese medicine.” But he did see the need for its promotion – most of the country’s 500 million people had only Chinese medicine to turn to. “Therefore, we must strive for the complete unification of Chinese medicine,” he opined. “That would be a great contribution to the world.”

Today Chinese President Xi Jinping has taken up the cause, which other state actors have also lined up behind, including the World Federation of Chinese Medicine Societies, which represents some 230 TCM organisations. “It is clear that the World Federation of Chinese Medicine Societies is involved in an active push to internationalise TCM,” according to Aron White, wildlife campaigner at London-based Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA).

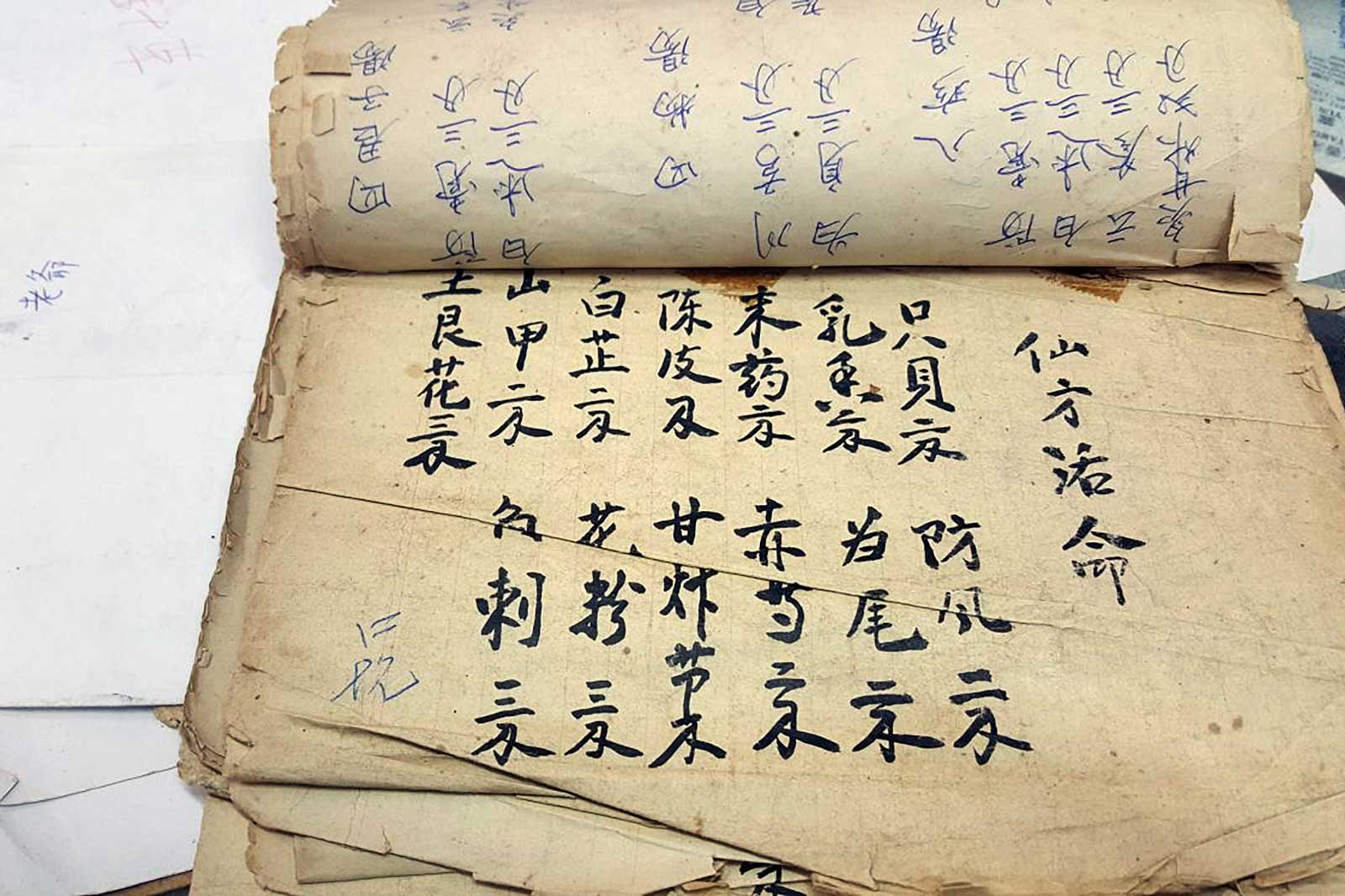

In China, homegrown treatments taken down in classical texts are a source of national pride that also make up one third of the country’s healthcare.

In 2016, China’s highest state administrative authority revealed plans to extend TCM services to all areas of medical care, with access for every one of its citizens by 2030. This was cemented by the Law on Traditional Chinese Medicine, approved by the National People’s Congress (NPC) Standing Committee (SC) later that year, to give TCM a larger role in the Chinese health care system, essentially legislating TCM’s “integration” into conventional medicine, both within China and beyond.

To meet this goal, Beijing will team it with another lofty ambition: the trillion-dollar Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), to bring the ancient Silk Road, which moved goods and ideas from Asia to Europe, to the 21st century.

According to Huang Wei, deputy director of the NPC SC commission for legislative affairs, speaking to state-owned media Xinhua, the law on TCM was to give the 2,500 year old system of “medicine with Chinese characteristics” new standing and reach to “improve global TCM influence and give a boost to China’s soft power.”

The State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine put the industry’s value at $130 billion a year, of which $295 million is exports of herbal medicines to BRI countries.

These figures hint at a gap in the market which Mao first identified: people across Southeast Asia and beyond who lack access to evidence-based medicine – for example, Vietnam’s 150,000 cancer patients who have just 25 radiotherapy machines between them.

In a 2016 white paper, the State Council proclaimed “the time has come for Traditional Chinese Medicine to experience a renaissance.”

Today that renaissance is taking shape. As tarmacs, railway tracks and bridges are laid in BRI host countries, dozens of hospitals and clinics are breaking ground from Morocco to Malaysia, offering what China has called a “gift to the world.”

But this gift is a death sentence for the animals which are snatched from the wild, skinned alive or put behind bars to fill prescriptions for everything from epilepsy to erectile dysfunction.

Besides rhino horn, remedies call for bile from the gallbladder of bears, the scales of pangolins, and for tigers, the TCM apothecary has a use for every part, from tooth to tail. The most prized formulation remains tiger bone wine.

In ancient times, the image of the “brave tiger” was everywhere, from silk paintings to wine bottles, according to Lixin Huang, Executive Director of the American College of Traditional Chinese Medicine in San Francisco. “He was revered for his greatness, his fast speed… he’s very strong.”

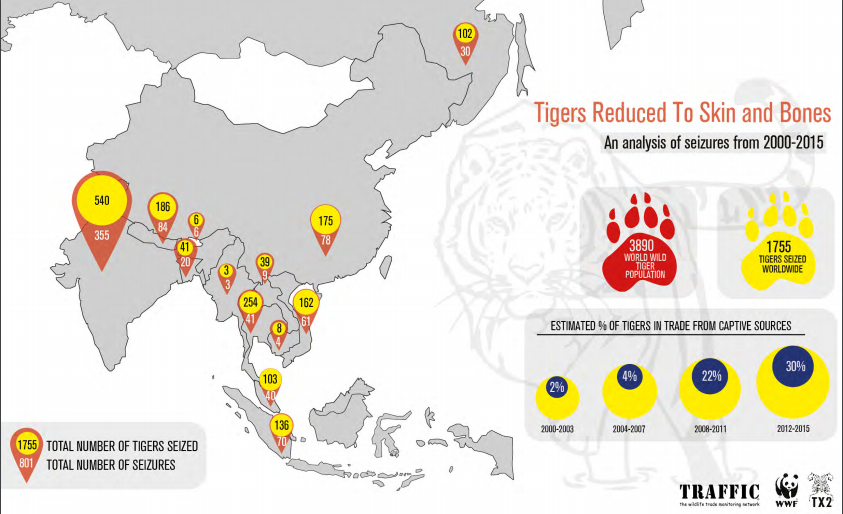

Tiger bones bottled in rice wine are thought to alleviate rheumatism and even prolong life. In pursuit of health and long life, this ancient practice is literally drinking tigers to death.

To China’s credit, it did take action. “In the mid 1990s, the Chinese government completely banned the use of tiger bone and rhino horn,” says Huang. “They were totally removed from medicine.”

During that time, alternatives were used. “Nobody died because of not having tiger bone or rhino horn to save their lives,” she says. “Substitutes were used; substitutes are the future.”

And yet across the country there are hundreds of facilities – zoos and tourist attractions – that provide “ample cover for the illegal wildlife trade [and] trigger the poaching of wild animals whose organs are desired more so because of their freedom,” says Goodrich.

Take Xiongsen Bear and Tiger Park in Guilin. In 2008, the sales manager lamented that he couldn’t advertise his wares due to the Beijing Olympics. “Foreigners just don’t understand,” he told reporters from South China Morning Post. “Chinese people know that tiger is the best medicine in the world. It cures so many things. It makes you strong. It makes a man more virile.”

Over the years, the Chinese government raised the possibility of lifting the ban, claiming that it may aid conservation of tigers. In October 2018, Beijing attempted to do so, but after national and international outcry, temporarily reinstated it.

But the reasons for wanting to lift the ban are likely less altruistic, namely “concerted lobbying efforts on the part of tiger farmers to open up the trade in tiger bone in China,” explains White.

Recent reports also suggest China is succumbing to pressure from tiger breeders who were “banking on something that was illegal being legalised in the future,” notes White.

And groups which had previously lent their support to the ban are now silent. In November 2018, the influential World Federation of Chinese Medicine Societies (WFCMS) held the World Congress of Chinese Medicine, at which it reversed its position and refused to give statements discouraging the use of tiger bone and rhino horn in TCM. According to White who was in attendance, the subtitle of the congress was “the Belt and Road TCM academic communications.”

“People have always been open to variety and holistic medicine,” says Chin. “Accessibility to such alternatives will definitely boost curiosity.” Strict adherence to the spirit of the classical texts which used a cocktail of plant and animal substances, together with scant labelling and ingredient lists, means medicine may contain endangered animals without consumers’ knowledge.

Just last month the threat to these animals was raised even further – by none other than the World Health Organisation.

WHO decision threatens Southeast Asia’s wildlife

On May 25th, the World Health Organisation (WHO) formally recognised Traditional Medicine (TM), including TCM in its influential medical compendium, the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), for the first time. The manual will be adopted as a reference for all WHO member states starting in 2022.

The decision was met with much fanfare within China, with one article in state-owned newspaper Xinhua calling it a “major step for Traditional Chinese Medicine’s internationalisation.”

This is not an overstatement – the ICD is a hugely important document which sets the healthcare agenda in over 100 countries, influencing allocation of 70% of global healthcare expenditure, including insurance reimbursements, and how doctors make diagnoses.

The ICD now includes Spleen Qi Deficiency and Liver Qi Stagnation alongside conditions like diabetes and asthma.

Statements from the WHO hint at what motivates its recognition of TCM: the “integration of TM into insurance coverage and reimbursement systems, in line with larger WHO objectives relating to universal health coverage.”

While the thought of diagnosis of TCM-labelled conditions and prescription of TCM remedies – let alone insurance payouts – angers some western medical practitioners, the WHO’s goal of universal health coverage by 2030 aligns with China’s own ambitions.

Under the former director-general Margaret Chan, whose tenure ran from 2006 to 2017, the organisation warmed to TCM, according to an editorial in Nature. During her directorship, Chan spoke favourably of TCM, remarking in a 2016 speech in Singapore that the practice had prevented or delayed heart disease by pioneering “interventions like healthy and balanced diets, exercise, herbal remedies and ways to reduce everyday stress.”

In an address in Beijing in November 2016, Chan heaped praise on China’s healthcare advances, and plans to spread TCM. “What the country does well at home carries a distinctive prestige when exported elsewhere,” she said.

Two months later, President Xi travelled to meet Chan in a historic first visit to WHO headquarters in Geneva. He came bearing a lifesize bronze statue of a replica of the first teaching model for TCM practice.

Where’s the evidence?

Amongst those who have studied TCM’s plant-based pills and potions, many note they may actually be ruinous to health.

Dr. Arthur Grollman, a professor of pharmacological science and medicine at Stony Brook University in New York conducted research on Aristolochia plants, long hailed in TCM for their supposed ability to relieve gas, pain and other ailments. What he found was deeply disturbing. Aristolochic acid in the plant can cause kidney failure and cancer. Found in many TCM remedies, it may explain Taiwan’s rates of kidney cancer, the highest recorded in the world.

In statements, the WHO claims its decision is a “not an endorsement of the scientific validity of any TM practice or the efficacy of any TM intervention” but a tool which “provides the means for doing research and evaluation to establish efficacy and safety of TM.”

But data gathering aside, for many in the medical science community, recognising TCM as an equal to medicine which has a basis in science and proven track record will come back to haunt the WHO. Donald Marcus, an immunologist at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, told scientific journal, Nature, “at some point, everyone will ask: why is the WHO letting people get sick?”

Pangolins in perils

The pangolin, or scaly-anteater, is an animal which could soon slide out of existence. Despite the highest form of protection under a global treaty on international trade in its parts, all eight species of pangolin are threatened with extinction, three of which live in Southeast Asia. Elusive and nocturnal, pangolins are difficult to track down and well armed against predators but once found by poachers they are easily caught as they instinctively roll up into a ball, their armour-like scales facing out.

Pangolins die in agony, boiled alive to remove their scale which are roasted and sold on the black market as lactation stimulants, relief from skin disease and even hangover cures. Just like rhino horn, pangolin scales are made of keratin, the same things found in human hair and fingernails, making consumption the pharmacological equivalent of chewing your nails.

It’s not known how many are left, says Chris Hamley, senior pangolin campaigner for EIA. But seizure data tells us they are the most trafficked animal in the world, for which China is to blame. “Without a doubt, China’s continued use of pangolin scales and meat is a major driver of poaching and trafficking. An expansion in the use of TCM products globally,” says Hamley via email “is very likely to lead to further growth in demand for pangolin products.”

Recent huge busts reveal the extent of the trade: 8.2 tonnes of scales seized in Malaysian Borneo, followed by a haul believed to be from as many as 14,000 pangolins along with the largest ever shipment of rhino horns, through Hong Kong. Hong Kong, incidentally is considered by China to be a hub and super-connector in its Belt and Road infrastructure.

So far, the WHO has only released statements to say its recognition of TCM “does not mean we recommend or condone the use of animal parts such as rhinoceros horns.”

But such statements don’t go far enough, say wildlife scientists. “Any recognition of Traditional Chinese Medicine from an entity of the World Health Organization’s stature,” said Goodrich, “will be perceived by the global community as a stamp of approval from the United Nations on the overall practice.”

“Crucially, use of threatened wildlife is still endorsed officially by Chinese government,” notes White. “The official state Pharmacopeia still lists pangolin scales as an ingredient, and formulations which use leopard bone.”

This explains the dissatisfaction with the WHO stopping short of condemnation, but instead recommending the enforcement of the international treaty, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora [CITES], which it notes “protects rhinos, tigers and other species.”

Dr. Anish Andheria, President and CEO of Wildlife Conservation Trust, said the recommendation showed that the WHO was at cross purposes, likening it to an organisation which promotes tree planting in an ailing forest while incentivising “saw mills along the periphery of that very forest.” He said further that the WHO should explicitly commit to ensuring that its recognition of TCM, “does not allow the violation of either national or international conservation or trade-related laws.”

While progress has been made in stopping the trade in some wildlife parts, not all animals have been so lucky. “The fight against illegal trade of rhino horn and ivory,” Chin explains “has gained much political traction mainly because these products are easily distinguishable.”

Farmed for their bones

There are now more tigers behind bars than there are in the wild.

As many as 6,000 of these tigers are in facilities in China, according to the government’s own figures, where they languish in cramped cages so small they cannot turn around. An estimated 2,000 more tigers are similarly caged across Thailand, Laos and Vietnam.

Rather than phasing out tiger farms, in accordance with its own ban, China allowed them to continue. “In fact the number of tiger facilities engaged in breeding tigers… has gone up,” says Debbie Banks, tiger campaigner for EIA.

To date, Laos is the only country has which stated their intention to phase out tiger farms – in 2016. “But we still haven’t seen any real progress,” says Banks. “In fact, last year, the Prime Minister decreed that the tiger farms that existed in the country could convert to tourist attractions.”

This is a move that brings to mind the horrors witnessed at Thailand’s Tiger Temple, a Buddhist monastery where for over a decade, monks walked tigers on leads and tourists snapped selfies with the big cats. When Thai authorities raided the complex in 2016, they seized 137 live tigers and uncovered the bodies of over 70 cubs in a freezer, proof of an illegal breeding operation.

Andheria fears that other such nightmare facilities could spring up in the aftermath of the WHO decision, causing “an explosion of illegal, poorly managed and cruel captive breeding stations.”

As to those behind the tiger farms, “many of the businesses, individuals and companies… are actually criminal enterprises,” says Banks.

Cash for ecocide

The illegal wildlife trade is big business, which the US Government Accountability Office report estimated is worth $23 billion a year. When it comes to organised crime, wildlife trafficking is the fourth most lucrative black market in the world, behind the trafficking of drugs, people and arms.

This criminality which props up TCM is the rule rather than the exception. The UN’s own Office for Drugs and Crime (UNODC), has shown that “illegal wildlife trade is driven by the demands of the traditional Chinese medicine,” says Samyukta Chemudupati, forensic trainer and wildlife crime expert at WCT.

What’s more, as Interpol recently concluded in a warning to member countries, “Environmental crime often occurs hand-in-hand with such offences as passport fraud, corruption, money laundering and murder.”

For the unfortunate people who get caught in the crossfire of wildlife crime, the impacts don’t stop there, says White. “The impacts are on wider criminality, on corruption, on governance.”

Perversely the “aggravating circumstances” surrounding the illegal wildlife trade for TCM may be what brings perpetrators to justice, says Chin. Thai construction tycoon Premchai Karnasuta was caught in a wildlife sanctuary February 2018, surrounded by animal carcasses, including one from a black panther. He was cleared of charges of killing and eating the panther but later sentenced to a year in prison for attempting to bribe an official.

“When profits made from wildlife crime far outweigh the penalties,” says Andheria, “the resulting lack of respect for the law encourages exploitative and corrupt individuals to engage in such detrimental practices.” He adds that it’s often the guardians of wildlife, like rangers, forest staff and the forest-dwelling communities who are on the front lines – and pay with their lives.

What’s more, poaching syndicates use their turf to move more than horns. “The same routes used to smuggle wildlife across countries and continents are often used to smuggle weapons, drugs and people,” says Interpol.

Traditional Medicine is not the problem

Not all TM is bad though. “We should acknowledge the contribution of TM,” said Gilbert Sape, World Animal Protection campaigner. “It’s being practised in many communities around Southeast Asia, including in my own in the Philippines,” he explained in a phone interview. “It is cheap, it is accessible, it is effective, and a good solution – so long as animals, wild and farmed, don’t suffer as a consequence.”

Huang agrees that some TCM treatments can be effective. Acupuncture, more popular than ever in the US, has been shown to work “in certain medical conditions where Western medicine does not.” Word of mouth is doing the job. “Patients see real results, then they come back for more. They get the word out,” she says. “That’s how Chinese medicine got spread in the US.”

China continues to feverishly build its TCM medical tourism hubs in Southeast Asia, where 30 are destined for BRI countries. Since legal status has been granted by WHO recognition, TCM should be a booming industry within a decade.

But the danger to the animals and the environment is one that faces us all. The UN’s recent biodiversity report held a stark warning for humanity: if nothing changes, 1 million species could go extinct within decades. Those species play vital roles in the ecosystems that support human life.

“The report is an urgent reminder of how we must change our ways,” says Banks “and stop seeing species purely as a commodity, valued for the sum of their body parts.”

Until that change reaches Beijing, it is “Beyond doubt,” says Andheria, that “China’s promotion of TCM via their Belt and Road initiative will be a death knell for innumerable terrestrial and marine species across Africa and Asia.”

Time for many animals is running out.