Growing up in France, Patrick Samnang Mey’s childhood was filled with tales about Cambodia, but it wasn’t until he was 22 years old that he was able to visit for the first time. It wasn’t long before he packed his bags and relocated to Phnom Penh for good.

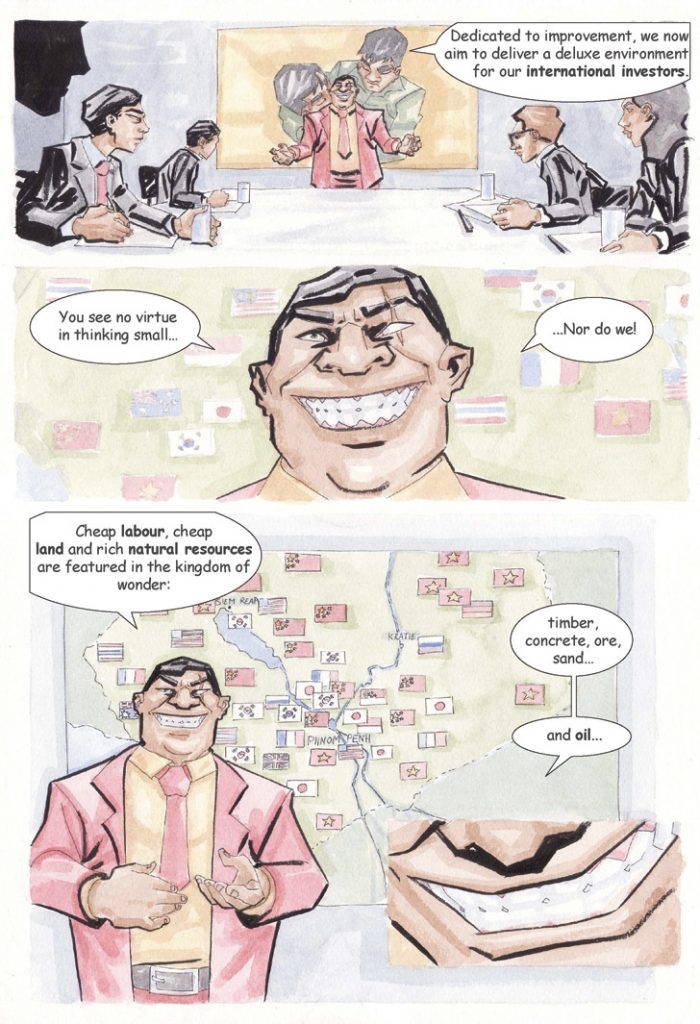

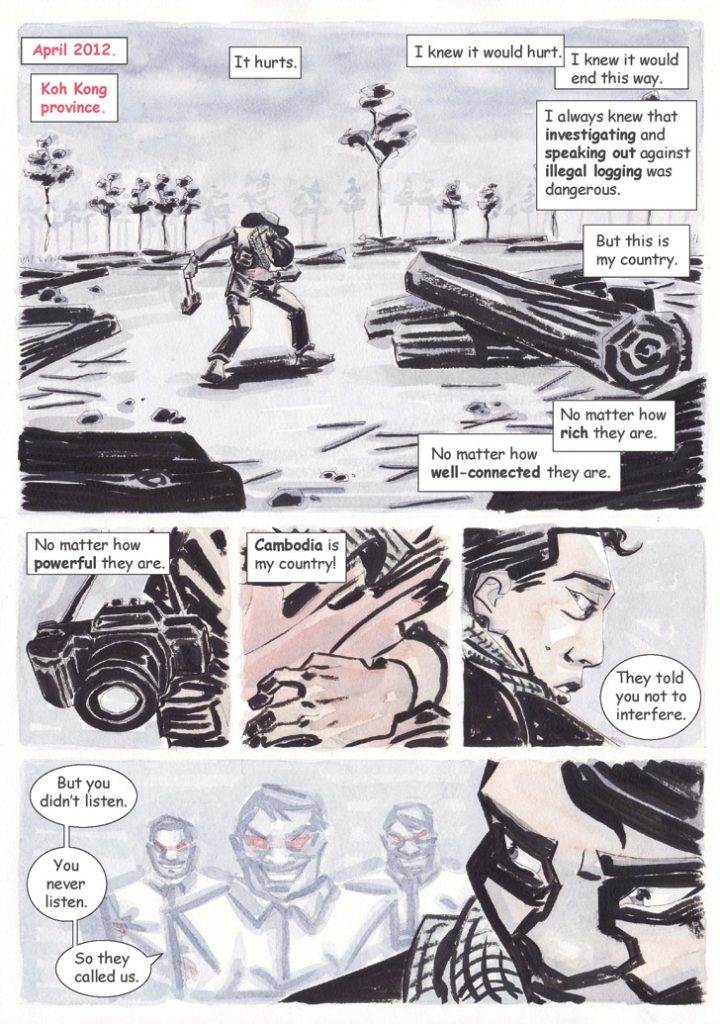

Currently based in Japan, last year Mey published a comic book titled Captain Cambodia, a political allegory that pits the titular hero against the ‘Red Eyes’, malevolent men often dressed in military fatigues.

What is the message behind Captain Cambodia?

It depends on the reader. A child can read Captain Cambodia, a teenager can read it or an adult can read it, and each will take something different from it. Maybe a kid won’t take much from it about politics, but someone who’s interested in politics will. For example, the opening scene takes place in Koh Kong in April 2012. It’s about someone who wants to stop illegal logging, and that’s a direct reference to the death of Chut Wutty [a Cambodian activist], who was shot dead. You have some other references to political figures, but I cannot say who is who.

So it’s quite a political comic book?

I’m very interested in politics; I read articles and reports every day. So I feel I have a responsibility to do something… I had a French education, and French artists used to be very politicised – and still are today somewhat. So if I think about Voltaire, Victor Hugo and Émile Zola, they got involved in the problems of their times. I’m not saying I’m Voltaire, but that’s what I was trying to do with Captain Cambodia.

What made you want to write it?

It was when [opposition leader] Sam Rainsy returned to Cambodia in 2013. There were huge crowds of Cambodians demonstrating every day. They weren’t scared any more.

What do you make of past Cambodian artists, such as the satirical cartoonist Ung Bun Heang?

I have a lot of respect for what he did. But the reality was he could not go back to Cambodia because of his art. When you get involved in those things, it’s not only you but your family as well. You cannot think only of yourself.

And you had some problems publishing Captain Cambodia?

Yes, I had some. At first, it was published by a national newspaper – in Lift, the Khmer youth pullout of the Phnom Penh Post. But, after page four, they decided to stop publishing it. They didn’t really explain why.

Why do you think it was?

I asked them if they had received some threats and they didn’t reply to my email. And they asked me if it would be OK for me to draw another comic book and they would write the story, but I said no. However, I can understand their decision to stop publishing it, and there’s no grudge.

Afterwards, I tried to publish it with a printing house in Phnom Penh, but they decided not to print it unless I got a letter of authorisation from the ministry of information. That would have meant I had to modify my work… that’s why I went with an e-book. Again, I understand those decisions. The printing house is

a company with 30 workers, so it was risky for them. They have to make a living.

Do you think it’s dangerous to publish political art in Cambodia?

If you want to do something related to politics it can be risky. Maybe not necessarily physically – although you saw what happened to the two [opposition] MPs [who were dragged from their cars and beaten recently]. Also, if you want to be an artist and you want a career in art, it can be risky for your career.

Do you think there is a politicisation of art in Cambodia?

It depends what you mean by political art. If you talk about the Khmer Rouge in a movie or in a book, that’s still politics. But if you mean what is happening now, in 2015, there aren’t many books or movies or other forms of art that are politicised.

What do you make of pro-government artists?

They have to make a living and, one day, Hun Sen will no longer be in charge. Then they will have to deal with it. Maybe they’ll say: ‘I had to do it.’ But I don’t know. It’s up to them. I don’t necessarily have respect for them, but I can understand they have to make a living. They can deal with their own conscience.