Parkour has risen from the suburbs of Paris to global fame – and its values of respect and inclusivity are helping it win over the culturally conservative city-state

On a Friday evening in Singapore, a group of men huddles beneath an underpass. A few minutes’ walk from Clarke Quay, the city-state’s nightlife mecca populated mainly by smiling tourists, the men wear tracksuits and trainers and stare ahead with gritted teeth. Then, one by one, they sprint at the wall opposite, using it as a springboard to propel themselves toward the ledge above. Those who make it pull themselves up to the street and vault over a chest-high railing, only to drop back down to repeat the spectacle seconds later.

A passerby stops and stares; his expression is one of sheer bewilderment. “What are you doing?” he asks the group. “This is parkour,” comes the reply. None the wiser, the man walks off into the night.

Parkour was developed by David Belle and his friends in the suburban town of Lisses, just south of Paris, in the 1980s. Informed by his father’s experience designing obstacle courses for the military, Belle grew up viewing his concrete surroundings as a world of untapped potential and, along with eight others, began using them to push the limits of the human body.

The close-knit crew would kick off walls into backflips, vault over railings, somersault off ledges, and leap from building to building in superhero-like fashion. In 1997, they formed the group Yamakasi and, over time, their experiments developed into a sporting discipline.

“We tried to create something with the body and the mind… because when people walk around a city, they just see what is in front of them,” Châu Belle, a cousin of David Belle and co-founder of the sport, told Southeast Asia Globe. “Parkour helped open our imagination… it helped us better understand ourselves.”

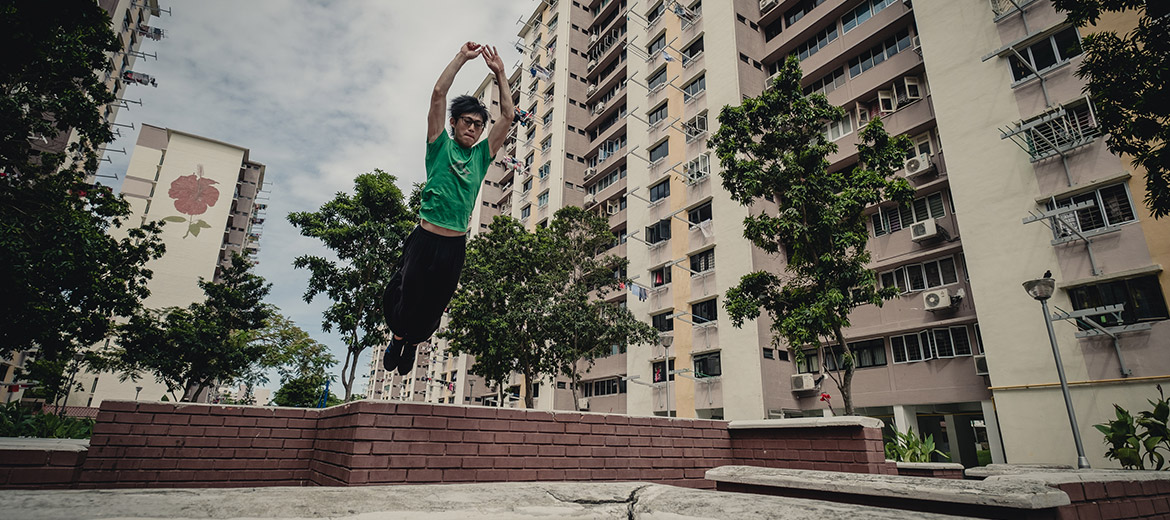

While the moves on display at Clarke Quay aren’t quite the death-defying jumps and awe-inspiring flips that animate the ever-expanding showreels of the Yamakasi founders, a quick YouTube search reveals that Singapore has many of its own acrobatic marvels.

Koh Chen Pin, or CP, is one of them. Inspired by Yamakasi, a 2001 film made by the renowned French director Luc Besson featuring seven of the group’s original members, CP began training ten years ago at the age of 14.

“I just decided to try it out with a couple of friends downstairs, just down my block at the playground – just climbing and jumping off the playground. It became a thing that we did every day after school,” he said. “Then I got more serious, so I started doing more research and found that it suits me very well.”

His research led him to Parkour Singapore, an online forum created in 2004, which helped Singapore build its very own parkour community.

“It was the first thing that people clicked on when they searched parkour in Singapore, and there were quite a number of good resources in the forums, which helped us all get started,” he said. “The most attractive feature was that people organised jams [open training sessions] on the weekends, which was how everyone started meeting and training together.”

During those early years, the internet was the only platform through which Singaporeans learnt about parkour, meaning its community was initially a very loose association, according to Chi Ying Tan, the founder of A2 Movements, Singapore’s first parkour school.

I think it’s very, you know: ‘Office worker by day, parkour by night.’ When I come at night, it’s like I have another self”

But that started to change in 2010, Tan said, when schools “offering coaching, insights and clarity to the public about parkour” began to spring up around the city. “They taught people that parkour is for everyone – that everyone can move… but also that hours of training and dedication are needed for practitioners to be successful,” he said.

The coaches at Move Academy, one of the schools that followed the arrival of A2 Movements and the school leading Friday evening’s class, were trained by Châu Belle and some of the other parkour founders.

According to CP, there are now 300 active practitioners in Singapore. The figure seems plausible, given that more than 2,000 people follow the Parkour Singapore Facebook page and the city-state has three dedicated parkour schools.

In CP’s eyes, Singapore’s advanced urban environment means it has “some of the best parkour spots in the world”.

“You can find training opportunities in every neighbourhood by just checking out the handicap ramps, fitness corners and neighbourhood walkways – rails, walls and benches are seen as obstacles for us to train on,” he said. “Many international athletes fly to Singapore just to train at our spots.”

The Move Academy group returns to the same spot near Clarke Quay on Sunday morning. As revellers nurse their hangovers from the night before and shuffle drearily along the nearby embankment, the group takes to the set of railings, working on individual moves before combining them into mesmeric sequences, known as ‘flows’.

After a few circuits, they slump against the wall to catch their breath, their muscles quivering in the mid-morning sun. A few moments pass before Raphael Revindran, a 23-year-old who studies business analytics at Nanyang Technological University, jumps on top of the railing and slowly unfurls his body to stand upright. He balances there for an impressive stretch of time before leapfrogging over the opposite railing in a move known as a ‘kong’.

Having practised the sport for five years, Revindran is one of the more experienced practitioners in Sunday’s class. Like CP, it was a film that first piqued his interest in parkour.

“I watched Jason Bourne and was like: ‘Whoa.’ He was scaling the walls during an escape scene. It was just one guy against so many people, and the only reason he got away from them was because he was quicker, more efficient,” he said. “That’s what got me into parkour.”

For Revindran, the sport gives him a “whole different life”, one that helps him escape the stresses of modern life and live in the moment.

“I think it’s very, you know: ‘Office worker by day, parkour by night.’ When I come at night, it’s like I have another self. I get to express myself through parkour,” he said. “It helps you switch off… When you’re in the movement – what we call the ‘flow’ – it’s all you have. It’s very Zen. That’s the best part.”

Yet while Hollywood stunt sequences were what brought him to parkour, Revindran was also keen to highlight that the sport is about more than putting on a show – something that founder David Belle hammered home in his 2009 book Parkour.

“When young trainees give me videos telling me to check out what they’re doing, I just take the tape and throw it away,” Belle wrote. “What I’m interested in is what the guy’s got in his head, if he has self-confidence, if he masters the technique, if he has understood the principles of parkour.”

That Singaporeans are embracing parkour’s core values would come as no surprise to David Belle, who told Red Bull’s lifestyle magazine Red Bulletin in June 2014 that the sport’s underlying philosophies are what make it so well suited to conservative cultures.

“Parkour’s future is in China and Russia,” he said. “People there are growing up in a society that demands a lot of discipline and hard work of them, but they still yearn for some freedom and self-fulfilment. With parkour, they can combine the two.”

Despite the sport’s impressive growth in Singapore, many members of the parkour community still complain that they face difficulties when training in public, with many considering their antics little more than dangerous acts of vandalism.

“I have to face the unappreciative stares of onlookers, and [have] had my fair share of police screening due to residents calling up the police,” CP said. “Usually it’s not too much to deal with, but it can be quite a pain [when] all I want to do is train.”

Overall, however, parkour appears to steadily be adding new disciples in Singapore, with the dedicated schools and a growing database of videos shared to social media helping spread appreciation and enthusiasm among the public. Some of the most skilled experts are even earning a full-time living from the sport.

Three years ago, the government invited practitioners, along with BMXers and skateboarders, to showcase their skills in the National Day Parade, an annual event celebrating the country’s independence from Malaysia. Since then, the government has been in talks with members of the community to build a parkour park, a development described by Ben Boeglin, one of the co-founders of Move Academy, as “the first step” toward the government officially recognising parkour as a sport.

“It’s about reaching [out] to a broader community to show that anyone can move and anyone can explore… to show it’s a good way to open the mind as well,” said Boeglin. “Parkour brings back that playfulness that we all have but kind of lose at some point.”