“Place every item of clothing in the house on the floor.”

So starts the chapter on clothing in Marie Kondo’s wildly successful book on The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up. After being published in English in 2014, it immediately was on the New York Times bestseller list and inspired millions of people around the world to simplify their lives by only keeping day-to-day things that bring them joy.

“When my clients think that they have finished, I always ask them this question. ‘Are you sure there’s not a single piece of clothing left in the house?’,” writes the author. “Then I add, ‘You can forget about any clothes you find after this. They’ll automatically go in the discard pile.’ I let them know I’m quite serious.”

After the Netflix series Tidying Up with Marie Kondo launched at the beginning of this year, charity shops around Australia were forced to ask people to stop donating clothing because they were inundated.

This madness for mindfulness comes from the best intentions – wanting to appreciate the items and people in your life as well as wanting to provide clothing to charities to clothe those in need. But after we donate our clothes to the charity shop and carry on with warm feelings and clean living, what happens to them? And for that matter, what happens to the clothing that’s left unsold in the store at the end of the season? Do they all find happy, loving homes?

The crisis of overproduction

It’s hard to picture the world without stores filled chockablock with hundreds of styles of super cheap – but cute – clothes that change every time you enter. But in fact, it’s only been about 20 years since so-called fast-fashion became what it is today – benefitting from the boom of online shopping and the US lifting limits on clothing and textile imports from certain countries, opening the floodgates to the US market.

These brands and online retailers were also able to take advantage of the relatively recent shift in garment manufacturing, originally from the US to China and then expanded to Southeast Asia, which made the most of those nations’ low wages and little regulation in order to start producing high-fashion styles quickly, cheaply and often. Even though the clothing was then being sea-freighted around the world after production, it was still more cost-effective to produce textiles and garments in Asia than in the States.

Between 1995 and 2014, while the rest of the world saw a 3.1 percent compounded growth on apparel exports, the developing Asia-Pacific region was soaring ahead with an average of 6.6 percent.

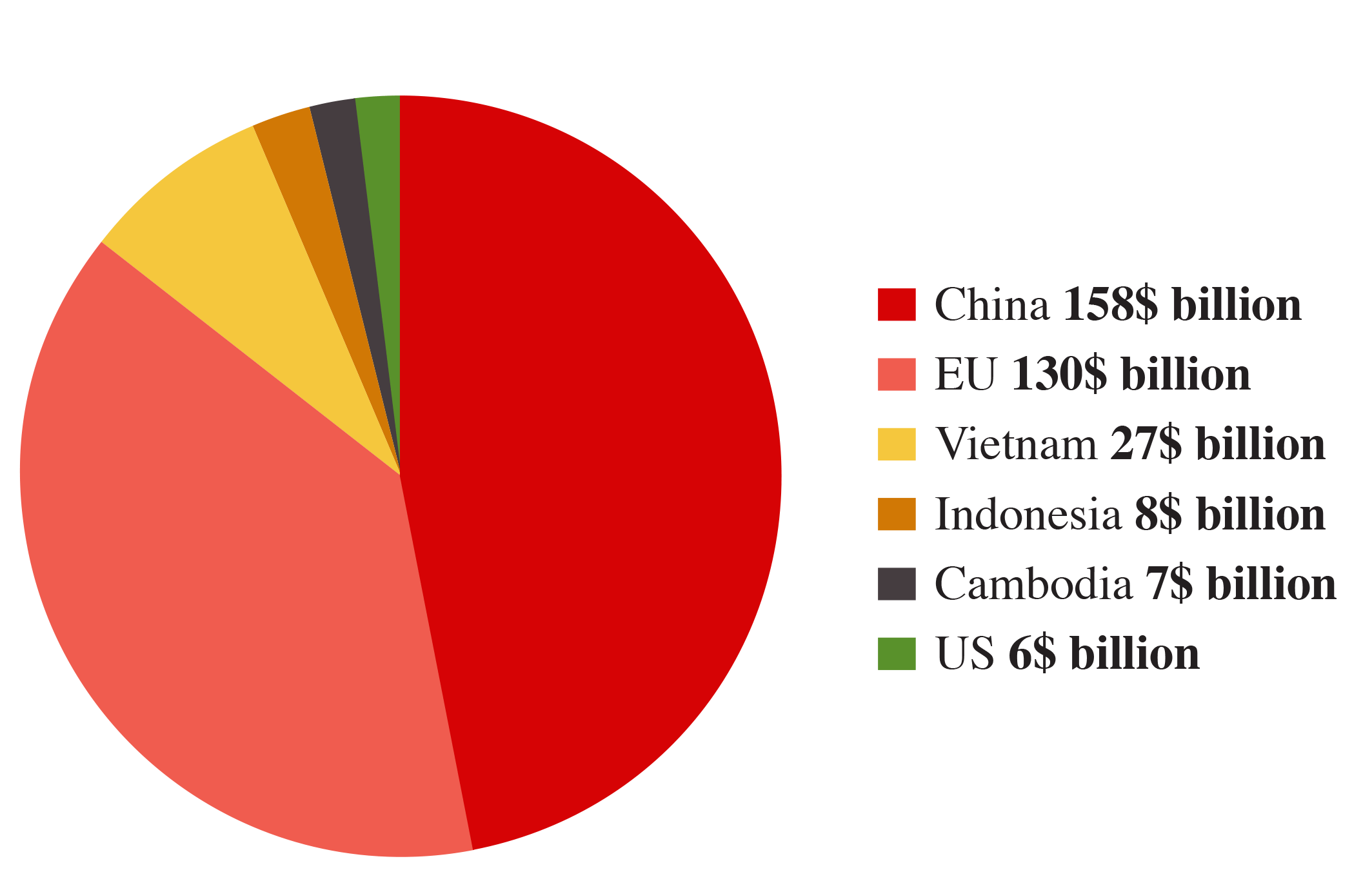

According to the WTO 2018 World Trade Statistical Review, China has been, and continues to be, the world’s largest exporter of both textiles and clothing, exporting $110 billion and $158 billion, respectively, in 2017. The same year, Vietnam maintained its position as the fourth largest garment exporter in the world with a value of $27 billion, and Indonesia and Cambodia also exported $8 billion and $7 billion, respectively. Whereas the world’s largest economy, the United States, exported only $6 billion-worth of garments – though it consumes $292 billion worth, making it by far the world’s largest consumer.

“Just keep it there until it’s rotten. We will burn them or dump them to the trash car”

“Mark”, former factory manager in Cambodia

In the last 15 years, clothing production has approximately doubled, and globally the industry is worth $1.3 trillion dollars, employing 300 million people along the supply chain. In short, the change in the last couple of decades has been both a boon for Asia and extremely profitable globally.

It also made it more cost-effective to overproduce clothes. Because orders have to be shipped to stores in the US from Asia, which takes roughly a month, companies would order more than they expected to sell, rather than risk running out of stock of a look that was only meant to be on the shelves for weeks anyway. So, from the outset on the demand side, there’s automatically going to be clothing left over.

But there is additional overproduction coming from the supply side as well. Garment factories need to be able to fill an order and, as always happens in production, mistakes will be made – so they over-order. Mark*, a former manager at a Taiwanese garment factory outside of Cambodia’s capital Phnom Penh, told Southeast Asia Globe that the factory that he used to work at regularly ordered extra of every component that goes into the garment. Garments may be cut out improperly, or have some damage during the production process, making them unsuitable for the customer. Where do the mistakes go? Says Mark: “to the trash car.”

When fabric arrives full of holes or has another defect that needs to be cut around – apparently a daily occurrence – it leaves extra scrap fabric to be discarded at the end.

“If it’s a very serious problem, the fabric manufacturer will send people to the factory to check and take the fabric back to the country of origin,” says Mark. “I don’t know how they handle the fabrics then. If it’s not very serious, the cutting department will avoid the defect part and still use it.” EDGE Fashion Intelligence reported that 15% of fabric meant for clothing ends up on the cutting room floor.

Clothing exports 2017

Because of potential errors on their side, fabric mills overproduce, too. According to Fashion Revolution’s 2015 White Paper, “It is estimated that a single textile mill can produce from 5% up to 25% of pre-consumer textile waste on its total yearly production.”

And though they try to stick close to making only the number of clothes that are needed for an order, garment factories will naturally end up with some perfectly usable garments leftover. Do they end up in the bin, too? Usually.

The times when clothing doesn’t get tossed are when the factory keeps them in anticipation of a reorder – or when they’re sold illegally.

“There’s the manufacturer’s number on the label, so you need to cut it in case the brand find out,” says Mark, adding that this is very rare. Although, given the number of stores in Phnom Penh alone that sell an assortment of mainstream brands, one wonders how rare a practice it really is.

Most brands have a policy regarding what must be done with their leftover garments in order to prevent them from being illegally sold, as the designs are their intellectual property to be protected. Some require for them to be cut down the middle, with video evidence of the destruction. Some brands, Mark says, ask that all leftovers are burned.

If the company does not have a policy, then the factory stores the leftovers in their warehouse.

“Just keep it there until it’s rotten,” Mark says. “We will burn them or dump them to the trash car.”

Burning questions

To this date, almost all fabric that goes into clothing is virgin, meaning made from scratch. Cotton, the largest fibre to be produced, is grown, picked, carded, spun, etc. every single time it is turned into fabric. The second most common – polyester – is likewise made new, and it is derived from petroleum. Textile production also uses a huge amount of water: around 93 billion cubic metres of water annually, according to the New Findings report by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, which is especially dangerous for drought-prone countries such as Vietnam – the tenth largest exporter of textiles in the world. So if more garments are produced, then more fabric is produced – and that means more natural resources are used.

From a business point of view, all of the overproduction makes sense – everybody wants to be able to deliver on what they’ve promised. It’s likely that none of the beneficiaries of this new fast-fashion arrangement was thinking about the long-term environmental effects of using raw materials to create two new looks a week instead of twice a year. And considering what has happened, it is likely that they were not thinking of the ultimate fate of all of the clothes produced.

But once the clothes are out the door and the cash has been counted, we still have to ask: where does it all go? With 7.7 billion people in the world, surely we can distribute clothing so that it’s put to good use.

“The incineration of fabrics is still one of the most widespread end-of-life destinations which is still considered green, which is one of the jokes of our time!”

Laura Francois, Singapore country coordinator for global nonprofit Fashion Revolution

“If we stop production everywhere, globally, we still have enough clothing for absolutely everybody,” says Laura Francois, Singapore country coordinator for global nonprofit Fashion Revolution, an organisation that advocates for labour and environmental reforms in the garment industry.

But the fact is that 85% of all clothing and textiles today ends up in a landfill, regardless of whether it was donated or never worn.

According to the MacArthur Foundation report, another 13% ends up being recycled into items such as wiping cloths, mattress stuffing and insulation – although these will find their way to the landfill eventually, making that 85% figure likely short of the true number. The rest is burned for energy; in Cambodia it’s often incinerated to furnace the Kingdom’s infamous brick kiln industry.

“The incineration of fabrics is still one of the most widespread end-of-life destinations which is still considered green, which is one of the jokes of our time!” says Francois. She, and most advocates for change in the industry, argue instead for a better solution: circular fashion.

The definition of circular fashion, according to the website of Dr. Anna Brismar, who is credited with coining the term five years ago this month, is: “clothes, shoes or accessories that are designed, sourced, produced and provided with the intention to be used and circulated responsibly and effectively in society for as long as possible in their most valuable form, and hereafter return safely to the biosphere when no longer of human use.”

Meaning, make clothes that are designed to be long-lasting from materials that are sourced responsibly and can biodegrade, so that all items are reused, recycled or composted.

Spinning new yarns

Recycling seems to be a perfect choice – all of these textiles come from natural resources and they’re soft; they should be able to break down and be remade easily.

In the opinion of SMART (Secondary Materials and Recycled Textiles) US industry association, 95 percent of textiles and garments can be recycled – but it’s not in the way you’d think of: “45% are re-used as apparel; 30% are converted into industrial polishing/wiping cloths and 20% are processed into fibre to be manufactured into new products.” The last five percent cannot be recycled because of mildew or other contaminants.

What about the more direct and intuitive act of recycling clothes to create fabric for new clothes? That process is more difficult.

Just as one sorts one’s household recyclables into kinds, fabric needs to be sorted as well – like fibre with like fibre. The technology exists to recycle mixed fibre fabrics, which are very common today in clothing (think of a polycotton blend, for instance), but it’s in its infancy and not efficient or economical on a large scale.

And there’s no incentive to invest in it. “In the [Southeast Asia] region, it’s rare because the people who lose out are the factories, the manufacturers,” says Francois, in a phone interview. “Those guys in the middle never get the good end of the stick; to actually invest in that technology is really, really tough.”

“Textile recycling, especially, is super intensive. It requires a lot of energy; it has a big impact upon the environment; it’s not super well developed”

Laura Francois

To the question of whether the brands could pay for the recycling machinery instead, she added, “The people that have the money and should pay for that technology are the brands, but those brands manufacture in so many different factories that why would they pay for one? It doesn’t make much sense because if they pay for it then all the other brands will benefit as well. It’s not a good business move.”

There are independent businesses that are focused specifically on recycling garments. The world’s largest, I:CO (short for I:Collect, in collaboration with SOEX), works with large shoe and clothing companies such as H&M and Adidas to place collection boxes in the stores. Customers are offered incentives by the stores to bring in their unwanted clothing and shoes, which I:CO then collects and sorts for either reuse, recycling within the garment industry or to be recycled for industrial purposes.

I:CO has collection points in stores in over 60 countries, including H&M stores in Southeast Asia – and a sorting plant in Malaysia.

Asked by email what percentage of items collected can be recycled in each category, I:CO Head of Marketing & Communications Lars Spicher said that roughly 60 percent is reused, 34 percent is recycled for industrial processing and about 6 percent goes to “professional disposal for energy” – meaning incinerated.

Francois thinks that looking to recycling as a silver bullet is unrealistic, which is perhaps supported by I:CO’s percentages: “In my opinion, recycling in general, when you think about what it actually does to the human psyche, it allows us to think that things disappear. But textile recycling, especially, is super intensive. It requires a lot of energy; it has a big impact upon the environment; it’s not super well developed.”

To the problem of recycling blended fabrics, Spicher admitted, “Not all garments are currently recyclable and, of course, some countries are not yet equipped with well-functioning waste management… I:CO and its Holding SOEX are therefore developing and implementing new recycling technologies in order to come closer to the goal of circularities in the textile industry. We are seeing advances on the horizon – but very slowly.”

In the meantime, Spicher says, they are advocating for design companies to use sustainable materials in their collections – another step towards circular fashion. “This change is being increasingly perceived and promoted by us and the entire fashion industry. Consumers are now also sensitised.”

In addition to sourcing sustainable materials, circular fashion advocates argue that design companies need to order less, produce less – much less – and upcycle their clothing, meaning make new designs using old stock.

And what can the consumers do? Buy secondhand clothing, buy less clothing and shop with the intention of wearing each piece a lot. “The best thing to do would be to buy only the things that you love and little else,” says Francois.

Meaning, be mindful and make sure to give your clothes a loving home.